[4]

[4]

Racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare have been well established in the literature. Reasons for disparities include cultural beliefs, socioeconomic differences, language barriers, and discrimination or bias in the healthcare system. A 2003 IOM report confirmed racial and ethnic minorities receive lower quality healthcare and have poorer outcomes than their Caucasian counterparts.1 A 2019 Medicare study found significantly decreased rates of surgical intervention among racial and ethnic minorities.2 The US Census Bureau reported that minorities comprised 38.4% of the population in 2015; by 2050, it is projected that non-Hispanic whites will no longer be the majority group in the United States.3 The increasing minority population has hastened the need to define, understand, and reduce these differences. Furthermore, disparities in healthcare and health outcomes will become increasingly economically burdensome.

Disparities in musculoskeletal care has been a topic of increased interest in the past decade. Schoenfeld et al et al reported that racial and ethnic minorities are at increased risk of complications and/or mortality after orthopaedic surgical intervention.4 Several other studies have demonstrated decreased utilization and access to orthopaedic care among minorities, such as joint replacement and spinal surgery.

Race and ethnicity also have an impact on the prevalence of certain musculoskeletal conditions. Ankylosing spondylitis and osteoporosis are examples of conditions for which ethnicity is a strong risk factor. Further research is needed to determine whether several other musculoskeletal conditions are impacted by ethnicity.

Racial/ethnic groups in the BMUS report are defined based on the major databases analyzed for this report. The six groups included in the databases are white, black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, and other. Hispanic ethnicity applies to persons of all races, therefore they are identified by their ethnicity, while other persons are defined as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic other. Due to small sample sizes, non-Hispanic other persons include Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, and others.

To broaden the scope of ethnic and racial differences and disparities, a literature search was also conducted. Findings on the impact of musculoskeletal diseases on more specific races and ethnic groups are discussed by condition. Data findings are presented to provide a snapshot of differences and disparities. However, the NEDS database, the largest database, does not include a race/ethnicity variable, thus the importance of differences in emergency department visits is unavailable.

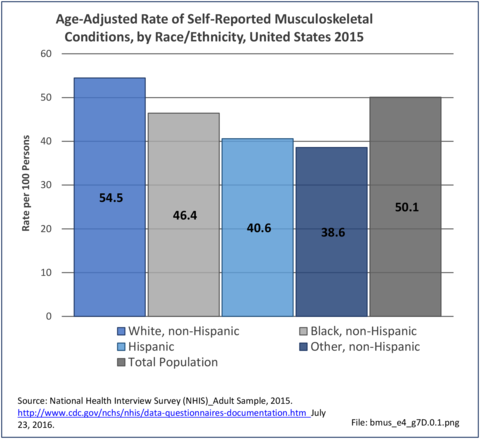

Non-Hispanic white persons report experiencing more musculoskeletal conditions in the previous year than members of other racial/ethnic groups. In 2015, 54.5% of non-Hispanic white persons reported they had at least one musculoskeletal condition, compared to 46.4% of non-Hispanic blacks, 38.6% of non-Hispanic others, and 40.6% of persons of Hispanic ethnicity. Chronic joint pain was the most frequently mentioned condition among all persons, with knee pain the most common joint. Non-Hispanic black persons reported back pain radiating down the leg (11.0%) at nearly the same rate as non-Hispanic white persons (11.4%), and a slightly higher rate of carpal tunnel syndrome (4.2% vs. 3.5%). (Reference Table 7D.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

The burden of musculoskeletal conditions can be defined in economic terms or as it affects those suffering from these conditions. In this section, burden is defined in terms of limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) and as bed or lost work days.

Approximately half of persons reporting musculoskeletal conditions also report they suffer limitations in ADL as a result of these conditions. Among non-Hispanic white persons, 28.7% reported limitations, 24.8% of non-Hispanic black persons have limitations, 18.7% of non-Hispanic other persons, and 18.6% of those of Hispanic ethnicity. Arthritis and back/neck problems are the most common conditions causing limitations. (Reference Table 7D.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

Bed and Lost Work Days

Non-Hispanic black persons report the highest number of bed days in the previous year due to musculoskeletal conditions (24.7 days on average), while those of Hispanic ethnicity lost, on average, the most work days (14.3 days). (Reference Table 7D.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

Racial disparities in the prevalence of spinal conditions have sparsely been discussed in the literature. Most spinal deformities, including scoliosis, have the higher rates of diagnosis in Caucasians (BMUS). A 2011 retrospective study of patients over 40 years old revealed a prevalence of almost twice the rate of scoliosis in whites compared to African-Americans (AA).1 Specific to adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS), African-American patients had higher curvatures at presentation compared with whites and Hispanics. Therefore, they were more likely to have surgery as their initial treatment.2 For this reason, AA patients may need to present at an earlier age for screening. There is a general belief that genetics play a role in progression of AIS; however, it is unknown which genetic factors or whether race is involved.

Lumbar radiculopathy is a spinal nerve root condition caused by nerve compression, inflammation, or injury in the lumbar spine. In a database study of a young, military population, lumbar radiculopathy was found to be more common among white patients.3 Lumbar spinal stenosis, a narrowing of the spinal canal resulting in nerve compression, is another major cause of low back pain and nerve symptom. Overall, hospitalizations for this condition have been reported to be much more common in whites. Blacks and Hispanics have lower rates of surgical hospitalization for lumbar spinal stenosis than did whites.4 Cultural barriers and attitude toward surgery may be responsible for this difference. In patients undergoing surgery for lumbar stenosis, blacks have higher complication rates, longer hospital stays, less likelihood of discharge home, and short preoperative and postoperative follow-up.5,6 African-American patients also accrue higher hospital-related costs and are prescribed fewer medications.5 Cervical spine surgeries have also been analyzed. African-American patients have higher rates of in-hospital complications and mortality than other ethnicities.7 Much of this difference was likely due to socioeconomic status, insurance status, and access issues.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an inflammatory arthritis that primarily affects the spine. AS is highly associated with the HLA B27 gene. AS is three times more common in whites than in blacks.8 This is mostly due to the lower prevalence of HLA-B27 in individuals of African descent. A prospective study by Jamalyaria et al compared the disease severity of AS in different ethnic groups. They determined that African-Americans, and Hispanics to a lesser degree, have greater functional impairment, higher disease activity, and greater radiographic severity compared to whites.9 The reason for this could not be determine; however, access to care and genetics are potential factors.

There is conflicting data related to racial differences in back pain. Hootman and Strine reported on 3-month prevalence rates of neck and back pain and found a higher prevalence in whites than other ethnic groups.10 Knox et al analyzed the rates of low back pain in military service members resulting in a visit to a health care provider and reported the highest incidence rates among African-Americans.11 The reason behind the variability is unknown; however, there is believed to be a genetic component. Importantly, a survey study found no significant differences in care-seeking behavior between racial groups for acute or chronic low back pain.12

Non-Hispanic white persons report experiencing neck/cervical and lumbar/low back pain at slightly higher rates in the previous year than members of other racial/ethnic groups. However, back pain with radiating leg pain was reported at similar rates among all racial/ethnic groups except for other/mixed non-Hispanic persons, who reported a lower rate.

In 2015, 36.4% of non-Hispanic white persons reported back pain, compared to 31.0% of non-Hispanic blacks, 30.3% of persons of Hispanic ethnicity, and 26.4% of non-Hispanic others. Low back/lumbar pain was mentioned about twice as often as neck/cervical pain. Respondents are asked if they have radiating leg pain only if the identify suffering from low back pain. Approximately one-third of persons with low back pain also reported radiating leg pain, with non-Hispanic black persons highest (39%) and non-Hispanic other/mixed persons lowest (34%). (Reference Table 7D.2 PDF [11] CSV [12])

Non-Hispanic whites (18.4 per 100 persons) were slightly more likely to seek healthcare for treatment of low back/lumbar pain in 2013 than non-Hispanic blacks (17.1/100) and Hispanics (14.2/100). However, non-Hispanic others/mixed race were much less likely to seek healthcare for back pain (7.3/100). Rates for non-Hispanic whites (6.2/100) and non-Hispanic others (6.0) were similar for healthcare visits for neck/cervical pain, but lower for non-Hispanic blacks (4.5) and Hispanics (3.0). (Reference Table 7D.2 PDF [11] CSV [12])

Non-Hispanic black persons report the highest number of bed days in the previous year due to back pain (8.7 days on average), while those of Hispanic ethnicity lost, on average, the most work days (14.1 days). (Reference Table 7D.2 PDF [11] CSV [12])

Research starting in the late 1980s and extending to 2011 shows a consistent pattern of doctor-diagnosed arthritis prevalence among races and ethnicities, although prevalence rose among all groups. Persons of Hispanic ethnicity and Asian/Pacific Islanders have lower arthritis prevalence than non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and non-Hispanics of other races. However, a study of the 2013 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS) participants residing in Hawaii of health disparities of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NHPI), Whites, and Asians found that NHPI males had a significantly higher prevalence of arthritis, which peaked twenty years earlier, than White and Asian males. The prevalence of arthritis peaked at 65-79 years in males and females in all racial groups, except NHPI males where it peaked at 45-54 years. At the NHPI peak age range, arthritis prevalence was 49.4% among NHPI males compared to White males (222.2%) and Asian males (17.9%). No significant differences were found among females.1

American Indians/Alaska Natives higher than non-Hispanic blacks and resembling non-Hispanic whites.2,3 A 2009-2011 study of prevalence rates among females only reported the same pattern, but with higher rates than found in both sexes.4 Arthritis-attributable activity limitation, arthritis-attributable work limitation, and severe joint pain were found to be higher for non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and multiracial or other respondents with arthritis compared with non-Hispanic whites with arthritis.3

Osteoarthritis, or degenerative joint disease, is the most common form of arthritis. The incidence of osteoarthritis in different ethnicities is similar. Disabling OA is at least as prevalent among African Americans and Hispanics as among non-Hispanic whites.5 African-Americans, however, report greater pain and activity limitation in comparison to Caucasians.6,7,8 African-Americans have higher prevalence of knee symptoms, radiographic knee osteoarthritis, and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis than whites,8 and 77% more likely to have knee and spine osteoarthritis together.9 Hispanics are 50% more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to report needing assistance with at least one instrumental activity of daily living and report difficulty walking.10 Prevalence of osteoarthritis of the knee is on the rise, due in part to the growing epidemic of obesity. Hispanic and African-American women have disproportionatly high rates of obesity leading to higher rates of knee osteoporosis, with subsequent quality-adjusted life-years losses, than found among Caucasian women.11

There is evidence of race-based differences in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Ethnic variations have been found in the clinical expression of RA, both in the frequency and types of SE-carrying HLA–DRB1 alleles,12 with non-Hispanic whites having the lowest percentage of rheumatoid factor positive results.13 Hispanics exhibit more tender and swollen joints than non-Hispanic whites, while African-Americans are slightly older at onset.12 African American and Hispanic patients have higher disease activity level, lower rates of remission, and worse functional status than white patients, in spite of more aggressive treatment strategies in recent years.13,14 There are also differences in utilization of disease-modifying anti-rheumatoid drugs (DMARDs), the gold standard treatment of RA. Certain studies suggest that treatment differences may be related to patient preference. Constantinescu et al found that fewer African-American patients preferred aggressive treatment compared to white patients with similar disease severity.15 This study suggests that improvement in patient literacy about rheumatoid arthritis could decrease the disparity in management.

Gout, one of the most common forms of inflammatory arthritis, is characterized by severe joint pain and destruction. A population-based cohort study demonstrated that African-Americans were at an increased risk of gout.16 African-Americans with gout have also been found to function worse than their Caucasian counterparts.17 Another database study found that African-Americans with gout were less likely to receive urate-lowering therapy with allopurinol.18 Studies have shown a similar efficacy of ULT between black and white patients.19,20 These results suggest that decreasing the disparity in gout treatment will improve disease severity in African-Americans.

Ethnic disparity has been widely studied in SLE, with findings that West-African immigrants experience SLE (lupus) more than those native to Europe or America, with many having the condition before migration. A San Francisco study found SLE was four times higher in African-American women than in Caucasian women. Among Asians, SLE is reported to be more frequent among Chinese settling outside China.21

Total hip and knee replacements, generally indicated for end-stage arthritis, are two of the most common and successful major surgical procedures performed in the United States. Outcomes after total joint replacement are similar between black and white patients after controlling for socioeconomic factors.22 Unfortunately, racial disparities in the utilization of these procedures has been demonstrated in multiple studies. A Medicare database study by Singh et al demonstrated that blacks are less likely to receive joint replacement surgery compared to whites. Importantly, the utilization disparity did not improve over an 18-year period. Blacks also had inferior outcomes including longer hospital stays and higher rates of readmission.23 Another prospective study revealed that blacks are less likely to receive a recommendation for joint replacement surgery; however, this difference appeared to be related to patient treatment preference.24 African American patients are also less familiar with TKA than their white counterparts and more likely to anticipate greater perioperative pain and longer recovery.25,26 Thus, patient education about the procedure is likely a major factor that will increase utilization of joint replacement procedures by African-Americans.

In 2015, non-Hispanic whites and Non-Hispanic blacks self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis (told be a doctor they have arthritis) at similar rates (22.6/100 persons and 22.2/100, respectively), while persons of Hispanic ethnicity reported a lower rate (15.4/100). Persons of non-Hispanic other/mixed race did not report in sufficient numbers to be cited. (Reference Table 7D.4.1 PDF [23] CSV [24])

The numbers reported for arthritis-attributable activity limitations as a total followed the same pattern as doctor-diagnosed arthritis, with non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks similar (11.1/100, 10.9/100, respectively), Hispanics much lower (5.7/100), and insufficient numbers of non-Hispanic others/mixed race to be cited. However, by specific type of limitation, non-Hispanic blacks report higher rates than other racial/ethnic groups. (Reference Table 7D.4.1 PDF [23] CSV [24])

In 2015, those of Hispanic ethnicity reported more lost work days due to arthritis, on average, than other racial/ethnic groups. (Reference Table 7D.4.2 PDF [31] CSV [32])

Considering only hospitalizations with an arthritis diagnosis, in 2013, non-Hispanic blacks had a slightly higher rate (2.8/100 persons) than non-Hispanic whites or Hispanics (2.6/100), with non-Hispanic others/mixed race much lower (1.1/100). The HCUP NEDS (emergency department) database does not report race/ethnicity, hence no numbers are available for other types of healthcare visits. Non-Hispanic blacks also had slightly longer hospital stays with an arthritis diagnosis. (Reference Table 7D.4.2 PDF [31] CSV [32])

Joint replacement is a common procedure performed to alleviate the pain from arthritis. As noted above, the literature reports lower rates of hip and knee procedures among non-Hispanic blacks. This finding is supported by the rates of all arthroplasty procedures performed in hospitals in 2013. Non-Hispanic white persons received 80% of hip replacements and 77% of knee replacements compared to the 62% of the population they represented. All other racial/ethnic groups had small shares of procedures than they represented in the population. (Reference Table 7D.4.3 PDF [39] CSV [40])

Race and ethnicity are important factors in the incidence of osteoporosis. The World Health Organization defines osteoporosis as a T score less than -2.5.1 African-Americans tend to have higher bone mass levels than Caucasians and Asians.2,3 In adults 50 years of age and older, approximately 10% of non-Hispanic white women have osteoporosis, compared with 6% of non-Hispanic black women and 10% of Hispanic women. It is estimated that an additional 50% of non-Hispanic white and Asian women have osteopenia, compared with 39% of black women and another 38% of Hispanic women.4,5

Osteoporotic fractures are a major health care concern due to their morbidity and mortality along with health expenditures. In 1995, the estimated health care costs associated with osteoporotic fractures was 13.8 billion.6 Decreased bone strength predisposes patients to an increased risk of fragility fractures, especially hip fractures. African-Americans have the lowest rates of hip fractures since they have the highest bone density.7 In a database study, Cheng et al reported that among traditional Medicare beneficiaries with fractures, osteoporosis was diagnosed nearly twice-as-often for white women compared with black women across all age groups.8 Ethnicity and race influenced the risk of fracture even after adjusting for multiple variables. Overall, the risk of fracture was 49% lower among African American women than among white women.9 Longer hip axis lengths have also been linked to an increased risk of hip fracture and hip axis lengths are reportedly shorter among African Americans and Asians, even after adjusting for height.10 African-American women who sustain an osteoporotic fracture, unfortunately, experience higher morbidity and mortality in comparison.11 This is possibly due to differences in hospital volume or it could reflect variations in care.

Race and ethnicity also are important factors in the screening and treatment of osteoporosis. In a retrospective review, Curtis et al found a significant disparity in recommendation for osteoporosis screening between AA and white women. Among Medicare enrollees, 33% of white women have screenings for BMD, but only 5% of African American women have such screenings.12 Among women with fractures, African Americans had a lower likelihood of both BMD testing and treatment.10,13 Hamrick et al reported that while 80% of white women received pharmacotherapy after osteoporosis diagnoses, only 68% of black women did.14 A cross sectional study by Curtis et al showed that African Americans are significantly less likely than Caucasians to receive osteoporosis medication. Minority women are less likely to receive hormone replacement therapy.15

In 2013, 892,600 patients discharged from hospitals in the US had a primary (first) diagnosis of osteoporosis. The distribution of persons with a primary diagnosis of osteoporosis did not reflect other data that indicates lower rates of osteoporosis among non-Hispanic blacks and higher rates among non-Hispanic whites and those of Hispanic ethnicity. Among this group, only 7% were classified as non-Hispanic whites.

Within the same time period, 540,600 patients were discharged with a fragility fracture diagnosis, and may or may not have had a diagnosis of osteoporosis. Among those with a fracture diagnosis, 82% were non-Hispanic white persons, with all other racial/ethnic groups accounting for only 4%-5% of discharges with a fracture. (Reference Table 7D.5 PDF [48] CSV [49])

The differences in hospital discharges for osteoporosis and fragility fractures from known prevalence rates may reflect treatment rates among racial/ethnic groups and coding of fractures before the underlying cause of the fracture in medical records, particularly among non-Hispanic white patients.

There is a paucity of literature regarding racial differences in sports-related injuries. Anterior cruciate ligament rupture is a common sports injury. A retrospective study of women’s professional basketball players over a 4-year span reported a higher rate of ACL tears in white players than their African-American counterparts.1 A difference in femoral morphology has been found between racial groups and may be a contributor to the potential difference in ACL injury rates.2 Another significant sports injury, lower extremity tendon ruptures, was analyzed in a military database study. Quadriceps, patellar, and Achilles tendon ruptures were examined. African-American service members had a significantly higher rate of lower extremity tendon rupture when compared to white service members.3 A biomechanical study showed a higher Achilles tendon stiffness in black athletes which potentially makes them more susceptible to rupture.4

Ankle sprains are the most common injury in athletic populations.5 Both AA and white races have a higher rate of ankle sprains than Hispanics.6 This is potentially due to the difference in type of athletic activities, for example soccer vs basketball.

Falls are an important cause of hospital admission and can lead to injuries such as hip and distal radius fractures. Whites have a higher incidence of falls than African-Americans.7 In a prospective study, Kiely et al also found a higher rate of falls in whites; however, after adjusting for confounding variables including types of activity and community characteristics, the difference was minimized.8 According to a retrospective study by Strong et al, in patients 65 and older admitted for falls, AA patients have a higher risk of mortality after discharge from the hospital.9 This highlights the need for improved follow-up after discharge.

African-Americans have a lower overall incidence of fractures than whites.10,11; however, there is minimal research on fracture risk other than in the hip. Much of this is related to higher bone density in blacks along with the difference in activities engaged in. Some studies have also investigated for disparities in the management of fractures. Opel et al found that after adjusting for insurance status and severity of injury, African-Americans had significantly lower odds of receiving surgical treatment for humeral shaft fractures than white males.12 The results suggested a possible bias in treatment decision-making, leading to less aggressive management in African-Americans.

Non-Hispanic whites self-report the highest rate of injuries (3.3/100 persons) for which they sought medical care in 2013-2015. Non-Hispanic other/mixed race persons reported the lowest rate 1.3/100). (Reference Table 7D.6 PDF [52] CSV [53])

Data for both self-reported injuries for which medical care was sought and for hospital discharges support research findings reported above. Non-Hispanic white persons represented two-thirds or more of reported injuries from falls, trauma, or other causes, but were a smaller share of trauma accidents than falls or other causes.

Among hospital discharges for injuries, 55% of non-Hispanic white persons were hospitalized due to a fall, compared to 33% of non-Hispanic black persons. Persons of Hispanic ethnicity had the highest share of discharges due to trauma injuries (34%) , followed closely by non-Hispanic blacks (31%). (Reference Table 7D.6 PDF [52] CSV [53])

Primary sarcomas represent the least common malignancies in bone, although osteosarcoma represents the most common nonhemoapoietic primary tumor of bone. Osteosarcoma is a primary malignant bone-producing tumor. In a review by Ottaviani, osteosarcoma had a higher incidence in African-Americans (AA) (6.8 per million persons per year] and Hispanics (6.5 per million) than in whites (4.6 per million).1 The reason for a potential higher incidence in blacks may be due to genetic factors, but it has not been determined.

Ewing sarcoma is a malignant tumor of bone and soft tissue. Race is an important factor in the incidence of ES, with Caucasians more likely to develop ES than African Americans or Asians. In a database study, Worch et al showed that ES is 8 times more likely to occur in the white population compared with African Americans and 1.9 times more likely to occur in the white population compared with Asian-Americans and Native Americans.2 Another database study by Worch et al., however, showed overall survival was significantly worse for patients. These results suggest a genetic component to the disease.3

Soft tissue sarcomas are the sixth most common primary cancer among young adults and adolescents aged 15-29.4,5 Musculoskeletal tumors included in this group include rhabdomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and liposarcoma. Hsieh et al. showed that AA had the highest incidence rates of fibromatous neoplasms, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Kaposi sarcoma among all racial/ethnic groups. This study also revealed that Hispanic males and females had significantly higher liposarcoma rates than other racial/ethnic groups.6 A database study by Alamanda et al found that African Americans encounter death due to soft tissue sarcomas at a much larger proportion and faster rate than their respective white counterparts. African Americans frequently presented with a larger size tumor, do not undergo surgical resection, or receive radiation therapy as frequently as compared with their white peers.7,8

Multiple myeloma is a cancer of plasma cells and is the most common malignancy arising in bone. Multiple myeloma (MM) is the most common hematologic malignancy among blacks in the US and the second most common hematologic malignancy in the country.9 A large database study concluded that blacks have an earlier onset and a higher incidence of MM This study also found African-Americans to have better survival rates, which is different than most conditions found in the literature.10 These results suggest a different disease biology. Fiala et al performed a database study regarding racial disparities in multiple myeloma treatment. After controlling for overall health and potential access barriers, black patients were found to be 37% less likely to undergo stem cell transplantation, and 21% less likely to be treated with bortezomib, an antineoplastic agent which is considered the gold standard in chemotherapy treatment of MM. Moreover, the authors found that the underuse of these treatments was associated with an increase in the incidence of death among black patients.11 The difference in treatment may be due to patient preference, patient education, or implicit biases in management. More research is needed to examine these factors.

Incidence of musculoskeletal cancers is reported in BMUS based on data published by the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER). Data is shown for bones and joints cancers but is not broken down for specific types of sarcomas. Myeloma (multiple myeloma) is a cancer of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Based on SEER data 2010-2014, non-Hispanic whites have a higher incidence of bones and joints cancers than do non-Hispanic blacks and those of Hispanic ethnicity, but all have very low incidence. Non-Hispanic white males had the highest incidence at 12 cases per one million persons. Myeloma has a higher incidence, with non-Hispanic blacks higher than non-Hispanic whites. Incidence was not reported for those of Hispanic ethnicity. SEER reported death rates for musculoskeletal cancers follow the same pattern as incidence rates but are much lower. (Reference Table 7D.7 PDF [60] CSV [61])

The impact of race and ethnicity on the etiology and management of musculoskeletal conditions requires more extensive investigation. The influence of race and ethnicity on the incidence of musculoskeletal conditions may be due to genetics along with difference in activities participated in. Genetic differences, however, have not been well defined in the vast majority of conditions. Clarifying this may lead to advancements in the management of certain conditions including osteoporosis, multiple myeloma, and spinal deformities.

The difference in incidence is also largely influenced by the lower rate of presentation by ethnic minorities to a physician. We also need to enhance awareness of any disparities in the management of musculoskeletal conditions. Race-based differences in the treatment of certain conditions may indicate an inherent bias. They may also be related to access issues and patient perception. The treatment of disabling osteoarthritis is a good example. Osteoarthritis has been found to be as prevalent in AA and Hispanic populations as in non-Hispanic white populations. Several studies, however, have shown that minorities undergo joint replacement procedures at a significantly lower rate. Ethnic minorities are less familiar with certain surgical procedures. Also, certain primary care physicians are less likely to refer patients to surgeons for consultations depending on their access to these services or their perception of what their patient's insurance may allow for. Unfortunately, AAs may have a higher rate of adverse outcomes.1 The reasons for this disparity are multifactorial but include less familiarity and lower expectations with the procedure in minority populations. Also, minorities tend to have procedures at lower volume hospitals which may contribute to more adverse outcomes.

Lastly, access to adequate postoperative care should be considered in adverse outcomes, be it from another family member that can afford to miss workdays or certain ancillary services provided to the patient.

A greater awareness regarding the disparities in musculoskeletal conditions and their management is needed. Further research into the reasons for differences in incidence of certain conditions will allow for better and possible earlier intervention. Moreover, enhanced understanding and defining the causes of racial disparities in the management of musculoskeletal diseases will allow improved and more equitable care in an increasingly diverse population.

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.1.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.1.csv

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d01png

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.0.1.png

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d02png

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.0.2.png

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d03png

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.0.3.png

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d04png

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.0.4.png

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.2.pdf

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.2.csv

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d11png

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.1.1.png

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d12png

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.1.2.png

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d13png

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.1.3.png

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d14png

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.1.4.png

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d20png

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.0.png

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.1.pdf

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.1.csv

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d21png

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.1.png

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d221png

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.2.1.png

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d222png

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.2.2.png

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.2.pdf

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.2.csv

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d25png

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.5.png

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d23png

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.3.png

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d24png

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.4.png

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.3.pdf

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.3.csv

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d26png

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.6.png

[43] https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00041424.htm

[44] http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/may/10_0035.htm

[45] http://healthfinder. gov/news/newsstorv.aspx?Docid=658088

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d31png

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.3.1.png

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.5.pdf

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.5.csv

[50] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d32png

[51] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.3.2.png

[52] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.6.pdf

[53] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.6.csv

[54] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d41png

[55] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.4.1.png

[56] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d42png

[57] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.4.2.png

[58] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d43png

[59] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.4.3.png

[60] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.7.pdf

[61] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.7.csv

[62] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d51png

[63] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.5.1.png

[64] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d52png

[65] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.5.2.png