[16]

[16]

Arthritis is an umbrella term that refers to joint pain or joint disease and encompasses more than 100 conditions. While there is no single accepted classification system for arthritis conditions, in general they are grouped as follows.

• Osteoarthritis [1]

• Inflammatory arthritis [2]

o Rheumatoid arthritis [3]

o Spondyloarthropathies [4]

o Connective tissue disease (eg, SLE, lupus) [5]

• Gout [6]

• Joint infection [7]

• Fibromyalgia [8]

• Juvenile arthritis [9]

• Joint pain/Joint replacement [10]

Osteoarthritis (OA) is widely recognized as the most common form of arthritis, and a major cause of pain and disability among US adults. Estimates of prevalence vary depending on how OA is defined: radiographic, symptomatic radiographic, or symptomatic only (self-reported presence of pain, aching, or stiffness). Radiographic OA is reported at higher prevalence levels than symptomatic, but symptomatic OA is more often cited from the self-reported databases.

From 2008 to 2014, 32.5 million US adults, or one in seven persons (14%), reported osteoarthritis and allied disorders, including joint pain with other specified or unspecified arthropathy, (herein called “osteoarthritis”) annually. Per previous research on the definition of osteoarthritis in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS),1 OA was defined as the presence of ICD-9-CM code 715 or a self-reported diagnosis of arthritis excluding rheumatoid arthritis and presence of ICD-9-CM 716 or ICD-9-CM 719. (Reference Table 8.13 PDF [11] CSV [12])

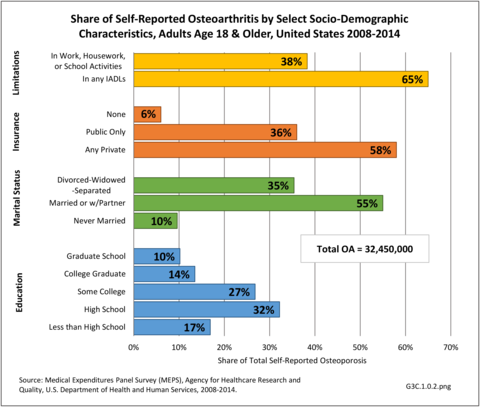

Across socio-demographic and health status characteristics, the following five groups represented the largest number of adults with OA by demographic classification: non-Hispanic whites (25.3 million), middle age (45-64 years) (14.8 million) or older adults (≥ 65 years) (13.8 million), those with private insurance (18.8 million), and those who were married/had a partner (17.8 million). (Reference Table 8.22 PDF [13] CSV [14])

However, total numbers do not reflect the share of the population group with OA. For example, females represent about 51% of the adult population in any given year, but comprise 78% of adults with OA. An even more disproportionate share of 18% of the population age 65 and older have OA (43%). This compares to 46% with osteoarthritis in the 34% of the population age 45 to 64 years. Non-Hispanic whites still have the highest share by race/ethnicity, comprising 65% of the population but 78% of those with OA, while Hispanics have the lowest (15% of population to 7% of adults with OA). Geographic region is not a major factor for OA, although the Midwest has a higher proportion of cases than it represents in the US population.

Share of the total OA population, however, does not give the whole picture. Since OA is closely linked to age, race/ethnicity and geographical regions with younger population segments will exhibit a lower overall share of OA patients. Both non-Hispanic black and Hispanic populations have a higher share of adults age 45 and older reporting OA than is found among non-Hispanic white adults. Hence, while non-Hispanic white adults represent the largest group of adults with OA, other race/ethnic groups have higher rates of OA. This same pattern can be seen in geographic regions, where the West has a younger population but higher rate of OA in the 65 and older population than is found in other regions. (Reference Table T3A.1.1.a PDF [19] CSV [20])

Joint Involvement in Osteoarthritis

Most OA diagnoses in both a hospital and outpatient setting do not specify the bodily site for which a healthcare visit is made. However, among those that are diagnosed with a specific site, the knee is the most common, followed by the hip. The knee accounts for about one-third (31%) of OA visits in all settings and is the only site identified in the data that meets reliability standards in all outpatient settings. Osteoarthritis in the hip accounts for 14% of hospital discharges, and 6% of physician office visits. (Reference Table 3C.1.0 PDF [23] CSV [24])

Healthcare Utilization

Osteoarthritis was diagnosed in 23.7 million healthcare visits in 2013, or 2.4% of all healthcare visits for any cause (Reference Table 3A.3.0.1 PDF [25] CSV [26]). It accounted for 10% of all hospitalizations and 2% of ambulatory visits.

Nearly 3 million hospital stays in 2013 had an OA diagnosis and it was the leading cause (46%) of hospitalization among all arthritis diagnoses. Osteoarthritis accounted for 45% of total hospital charges for arthritis diagnoses (cost charged but not necessarily paid), presumably in part because OA is the principal diagnosis associated with hip and knee joint replacements. Fewer than half (43%) of patients with an OA diagnosis were discharged to home or self-care, the lowest share of all arthritis diagnosed hospitalized patients. This is probably due to discharges to assisted living facilities or skilled nursing homes for rehabilitation following the hip or knee joint replacement. (Reference Table 3A.3.0.1 PDF [25] CSV [26]; Table 3A.3.1.1.1 PDF [27] CSV [28]; Table 3A.3.1.3.1 PDF [29] CSV [30]; and Table 3A.5.3 PDF [31]CSV [32])

Females hospitalized with OA outnumber males two to one, while two in three patients were age 65 and older and hospitalized at a rate of 4.5 in 100. Non-Hispanic whites had the highest rate of hospitalization for OA (1.4 in 100 persons), while Hispanics had the lowest rate (0.4/100). Residents of the Midwest region were also more likely to be hospitalized with a diagnosis of OA (1.5/100), while those living in the West were least likely (0.9/100). Regional differences are a product of age to some degree, with the mean age of the Northeast and Midwest about 4 years older than the West. (Reference Table 3A.3.1.0.1 PDF [35] CSV [36]; Table 3A.3.1.0.2 PDF [37] CSV [38]; Table 3A.3.1.0.3 PDF [39] CSV [40]; and Table 3A.3.1.0.4 PDF [41] CSV [42])

Osteoarthritis was diagnosed in 20.8 million outpatient visits in 2013 and accounted for one in five (21%) ambulatory care visits with any arthritis diagnosis. This was a rate of 1 in 12 (8.4%) outpatient visits for any diagnoses including an OA diagnosis. Visits per 100 were higher among females, adults 45 years and older, and non-Hispanic whites and blacks. Residents in the South had the lowest rate of outpatient visits for OA. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.1 PDF [43] CSV [44]; Table 3A.3.2.0.2 PDF [45] CSV [46]; Table 3A.3.2.0.3 PDF [47] CSV [48]; Table 3A.3.2.0.4 PDF [49] CSV [50])

Economic Burden

Combining direct and indirect costs for OA and allied disorders, average annual all-cause costs for the years 2008-2014 were $486.4 billion. Total incremental costs (direct and indirect costs directly associated with osteoarthritis) were $136.8 billion. (Reference Table 8.13 PDF [11] CSV [12])

Among all adults with osteoarthritis, annual all-cause per person direct costs were $11,502. Those reporting limitations had the highest all-cause per person direct costs: any limitation in work, housework, or school activities ($17,136) or any limitation in IADLs, ADLs, functioning, work, housework, school, vision or hearing ($14,146).

Annual total all-cause direct costs were $373.2 billion. The five socio-demographic groups with the highest total all-cause direct costs were: non-Hispanic whites ($300.7 billion); those with any limitation in IADLs, ADLs, functioning, work, housework, school, vision or hearing ($298.5 billion); any limitation in work, housework, or school activities ($213.0 billion); any private insurance ($216.5 billion); or who were married/had a partner ($200.4 billion).

Osteoarthritis incremental direct medical costs totaled $65.5 billion annually; average per person OA incremental costs were $2,018. (Reference Table 8.13 PDF [11] CSV [12], and Table 8.22 PDF [13] CSV [14])

Some 16.7 million adults of working age (18-64 years) with a work history had OA. The ratio of persons in the labor force without osteoarthritis (90%) is higher than for those with OA (69%), resulting in earnings losses due to OA.

On average, for the years 2008-2014, those without OA earned $6,783 more than those with OA, which represented a total of $113.2 billion in all-cause earnings losses for all U.S. adults with OA. Earnings losses attributable to OA were $71.3 billion; per person osteoarthritis-attributable earnings losses were $4,274. (Reference Table 8.13 PDF [11] CSV [12])

Lifetime cost attributed to knee OA in 2013 were $140,300. More than one-half (54%) of knee OA patients underwent total knee arthroplasty (TKA) an average of 13 years after diagnosis. The largest proportion of knee OA-related direct medical costs for those meeting TKA eligibility criteria was attributable to primary TKA.2

Inflammatory arthritis is a group of diseases characterized by inflammation of the synovial membrane in the joints and, often, other tissues throughout the body. Some forms of inflammatory arthritis are autoimmune diseases, conditions in which the body’s immune system attacks healthy tissue, also known as systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases (SARD). Examples of SARDs that cause inflammatory arthritis include rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome (SjS), systemic sclerosis (SSc), polymyositis (PM), and dermatomyositis (DM). Other types of inflammatory arthritis include axial spondyloarthritis (formerly called ankylosing spondylitis) and psoriatic arthritis, along with gout which is also considered a metabolic arthritis and discussed under it's own heading.

As a group, inflammatory arthritic diseases are characterized by joint pain, swelling, warmth, and tenderness in joints, and can cause deformity and loss of function of affected joints. Since these diseases are systemic, they may be associated with involvement of other tissues or organs including the skin, eye and bowel. In addition, in these diseases, blood tests provide evidence of inflammation and some conditions are useful markers that assess disease likelihood. Inflammatory arthritis conditions are sometimes difficult to diagnose and distinguish; all patients suspected of having an inflammatory arthritis should be referred to a rheumatologist for evaluation and management. Arthritis occurring in children and adolescents is referred to as juvenile idiopathic arthritis (formerly juvenile rheumatoid arthritis) and is discussed in the Juvenile Arthritis [9] heading.

Only the most common inflammatory arthritides will be discussed below. A listing of the many types of inflammatory arthritis and related conditions can be seen by clicking HERE [55].

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disease that produces inflammatory arthritis (stiff, painful, swollen joints, usually symmetrical). Rheumatoid arthritis is a form of polyarthritis and involves many joints, both large and small; it can also affect the cervical spine. Over time, RA can affect other organs (eg, eyes, lungs) and can lead to increased risk of cardiovascular disease.1

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic condition and, while it may occur acutely in some patients, onset is usually gradual. It can take months before a patient seeks medical attention, usually when joint pain (arthralgia) progresses to swelling and tenderness of the joint. As a systemic disease, RA is associated with symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, and depression. In RA, inflammation of the joint can lead to erosion or damage of cartilage and bone and eventual deformity. The patient with RA characteristically produces autoantibodies called rheumatoid factors and anti-CCP. Anti-CCP (cyclic citrullinated peptide) antibodies are directed to proteins that have a modified amino acid called citrulline. These antibodies occur in approximately 70-80% of patients and are important for diagnosis and early recognition.

Rheumatoid arthritis was historically categorized based on the American Rheumatism Association Functional Class and Anatomic Stage, both proposed by Dr. Otto Steinbrocker in 1949. The former was updated by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 19922 as follows:

Class I: Patient able to perform usual activities of daily living (self-care [dressing, feeding, bathing, grooming, and toileting], vocational [work, school, or homemaking] and avocational [recreational and/or leisure])

Class II: Able to perform usual self-care and vocational activities, but limited in avocational activities

Class III: Able to perform usual self-care activities but limited in vocational and avocational activities

Class IV: Limited in ability to perform usual self-care, vocational and avocational activities.

The revised classes were validated in a study of 325 patients using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ): mean HAQ disability index scores were Class I = 0.33, Class II = 1.02, Class III = 1.70 and Class IV = 2.67.

It is currently the usual practice to consider staging RA based on duration of signs and symptoms and the presence of autoantibodies and radiographic erosions. Hence, as currently defined by the ACR, RA is classified as follows:

Early RA = Signs and symptoms of < 6 months duration

Established RA = Signs and symptoms of ≥ 6 months duration or meeting the 1987 classification criteria

Seropositivity = presence of either rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA). Presence of erosions on radiographs of the hands/wrists.

In addition, one considers the level of disease activity at the time of the patient’s visit to inform treatment decisions. Several reliable and valid instruments are available for this purpose; most useful are the Disease Activity Score 28 [56] using either the erythrocyte sedimentation rate or the C-reactive protein marker, the Simplified Disease Activity Index [57], or the Clinical Disease Activity Index [58]. The latter does not require obtaining any laboratory tests to measure acute phase reactants. The ACR has published recommendations for the management of RA based on the above parameters, especially disease duration and disease activity.3

Although there is no cure for RA, early identification and treatment is important since current therapy can lead to significant improvement and reduce the likelihood for joint damage and progression to deformity. Therapy for RA involves a large group of medications that decrease inflammation and modify the course of disease. These agents are called DMARDS (disease modifying antirheumatic drugs) and have led to important improvement in overall outlook.

Prevalence of Rheumatoid Arthritis

As noted earlier in this report, clinical data are required to provide validity for estimating the prevalence of specific types of arthritis because the exact type of AORC causing pain and swelling is often unclear from observation. Prevalence of RA in the US is estimated to be between 1.3 and 1.5 million persons,4,5,6 roughly 0.50% of the adult population. Prevalence varies by sex, affecting 0.29%-0.31% of males and 0.73%-0.78% of females.6Also note that prevalence varies by age with highest ratios in older adults aged 65 years and older and lower ratios in declining 10-year age groups. The estimated prevalence of RA in the US population age 60 years and older is 2%.7

Healthcare Utilization

Rheumatoid arthritis effects overall health but may not be identified as the condition for which a patient is hospitalized. The NIS includes a separate variable identifying comorbidities of patients. Analyzing this variable, RA was identified as a comorbidity in 821,100 hospital discharges, or 2.7% of all hospital discharges, in 2013. However, when discharges were analyzed using the ICD9-CM codes, RA was diagnosed in only 512,600 discharges, or 1.7% of discharges for any diagnoses. Comorbidity designations are not made for all inpatients. Overall, 61% of discharges with RA diagnosed as a comorbidity also had an admitting diagnosis of RA, leaving two in five (39%) diagnosed with RA as a comorbidity but hospitalized for another cause. Common other forms of arthritis and associated diseases with RA as a comorbid condition include lupus (SLE) and fibromyalgia. (Reference graphs G3C.2.1.1 and G3C.2.1.2)

As previously noted, RA was diagnosed in slightly more than one-half million hospitalizations in 2013, representing 1.7% of discharges for any diagnoses. This is compared with the general prevalence rate of approximately 0.5%. Mean length of hospital stay and mean hospital charges were slightly higher than for all hospital discharges (106% and 109%, respectively). Nearly half (45%) of discharges with an RA diagnoses were dischared to additional care (short-term or home health), compared with 33% for all diagnoses discharges. (Reference Table 3A.3.1.0.1 PDF [35] CSV [36]; Table 3A.3.1.1.1 PDF [27] CSV [28]; Table 3A.3.1.3.1 PDF [29] CSV [30])

Rheumatoid arthritis was the first diagnoses recorded in 1.4% of total hip replacements and 0.3% of total knee replacements in 2013. (Reference Table 3A.5.3 PDF [31] CSV [32])

For RA, females outnumbered males three to one. Most RA hospitalizations occurred in those aged 65 years and older at a rate of 0.7 adults in 100 for this age group. No differences in rates were found by race/ethnic or regional group. (Table 3A.3.1.0.1 PDF [35] CSV [36]; Table 3A.3.1.0.2 PDF [37] CSV [38]; Table 3A.3.1.0.3 PDF [39] CSV [40]; Table 3A.3.1.0.4 PDF [41] CSV [42])

Rheumatoid arthritis was diagnosed in 6.4 million ambulatory visits and accounted for 0.7% of ambulatory care visits with an arthritis diagnosis, compared with the 0.5% prevalence rate in the US population. An RA diagnosis was made in 0.6% of physician office visits and ER visits; 0.8% of outpatient visits had a RA diagnosis. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.1 PDF [43] CSV [44]; Reference Table 3A.3.2.1.1 PDF [65] CSV [66]; Table 3A.3.2.2.1 PDF [67] CSV [68]; and Table 3A.3.2.3.1 PDF [69] CSV [70])

The distribution of ambulatory care visits by select demographic characteristics, when compared to all ambulatory visits for RA, was highest among females, and lowest among those younger than age 44 and among Black non-Hispanic and Hispanic racial/ethnic groups. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.1 PDF [43] CSV [44]; Table 3A.3.2.0.2 PDF [45] CSV [46]; Table 3A.3.2.0.3 PDF [47] CSV [48]; Table 3A.3.2.0.4 PDF [49] CSV [50])

Economic Burden

Estimates were calculated from 2008-2012 Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS) data; analysis was limited to those years because the ICD-9-CM code for RA was suppressed in the 2013 and 2014 MEPS data. MEPS respondents were classified as having RA if they met the following criteria: had a record with ICD-9-CM code 714, self-reported having ever been diagnosed with RA, and had at least five prescriptions or ambulatory care visits for RA. In the 2008–2012 period, each year, an estimated 1.7 million adults (0.8% of US adult population) had RA. Although slightly higher than the 1.3 million to 1.5 million previously cited by other sources, the numbers provide a similar rate of RA in the adult population.

Combining direct and indirect costs for RA, total average costs annually for the years 2008-2014 were $46 billion, with incremental costs, those costs directly associated with RA, of $21.6 billion. (Reference Table 8.13 PDF [11] CSV [12])

Annual average per person all-cause (diagnosis of RA along with other health condition diagnoses) medical expenditures for RA were $19,040. Across selected characteristics, the five groups with the highest all-cause per person costs were those who were college graduates ($25,526); had any limitation in work, housework, or school activities ($25,220); lived in the Northeast ($24,038); Hispanics ($22,871), and those with any limitation in IADLS, ADLs, functioning, work, housework, school, vision or hearing ($21,858). Lowest per person costs were among the uninsured ($8,674) and across the remaining subgroups, average per person costs were at least $14,387.

Total all-cause medical expenditures were $32.9 billion. Total costs include ambulatory care, inpatient care, prescriptions filled, and residual costs (ER, home health, medical devices).

For incremental medical expenditures (expenditures directly attributed to RA), mean per person expenditures for RA averaged $7,957 for the years 2008-2012. Aggregate medical expenditures (combined cost for all persons) in the United States for RA averaged $13.8 billion in each of the years of 2008-2012. (Reference Table 8.13 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 8.23 PDF [77] CSV [78])

The ratio of persons in the labor force without RA is higher than for those with RA in the general population, resulting in earnings losses due to RA. Among the estimated 900,746 working age adults (18-64 years) with a work history and RA, 56.1% had worked during the year compared with 87.9% of those without RA. Each year, those with RA earned, on average, $14,542 less than those without RA, which among all adults with RA totaled $13.1 billion.

For incremental medical expenditures, mean per person earnings losses attributed to RA averaged $8,748 per year in 2008-2012. Aggregate earnings losses for the United States due to RA averaged $7.9 billion in each of the years of 2008-2012. (Reference Table 8.13 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 8.23 PDF [77] CSV [78])

The cost of treating RA can be high. Older treatments of NSAIDS (aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib) and analgesics (acetaminophen, morphine, oxycodone) are readily available and inexpensive. However, many who suffer from RA cannot tolerate these drugs or they do not suppress the pain. A second level of drugs, the DMARDs (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs) designed to reduce symptoms and damage, have become more affordable than previously, but still cost between $1,500 and $2,000 annually.

The newest level of drugs, the biologics, remain very expensive. Biologics are genetically engineered proteins originating from human genes targeting specific parts of the immune system that fuel inflammation. The first biologic, etanercept (Enbrel), was approved in 1998, and was used to treat RA. Actual cost estimates have a wide range, an average $18,000 to $100,000 annually, depending on the type of biologic used.8,9,10,11 In addition, because most are administered through an IV or injection administered by a healthcare professional, there are additional costs. Higher medication costs have been found to be associated with age and comorbidities.12

Spondyloarthropathy (SpA) refers to a family of inflammatory arthropathies that primarily affect the vertebral column. This group differs from other types of arthritis, especially rheumatoid arthritis, in that, rather than primarily affecting the synovial lining tissue in the joints, it involves the connective tissue where the tendons and ligaments attach to bone (entheses). Furthermore, patients with these disorders usually have negative tests for both rheumatoid factor and antibodies to citrullinated peptides (autoantibodies seen in the majority of patients with RA), often have radiographic involvement of the sacroiliac joints, and may have ocular inflammation (i.e., acute iritis or uveitis). Symptoms are often termed inflammatory back pain which is gradual in onset, worse in the morning and improves with activity. Inflammation can also affect the large joints of the lower extremities, including the knees and ankles. In the spondyloarthropathies, sacroiliac joints can fuse, and new bone can form between vertebrae. This leads to ankylosing and can cause deformity of the spine. In some patients, the spine can become rigid.

Among the conditions included in the SpA family, axial spondyloarthritis (formerly known as ankylosing spondylitis [AS]) is the most common and refers to inflammation of the spine or one or more adjacent structures of the vertebrae. Axial spondyloarthritis causes inflammation of the tissues in the spine and the root joints (shoulders and hips) and may be associated with peripheral arthritis. Over time, patients can undergo fusion of the vertebrae, limiting movement. Axial spondyloarthritis has a hereditary component and runs in families. It affects males more than females and can occur at any age. Patients with SpA frequently have a genetic marker called HLA B27. Since HLA B27 occurs commonly in the otherwise healthy population (approximately 8% of the US), it is not used as a specific diagnostic marker. HLA B27 is less common in African Americans.

In addition to AS, the more common diseases in the (SpA) family are:

• Reactive arthritis (formerly known as Reiter’s syndrome), a reaction to an infection in another part of the body;

• Psoriatic arthritis, which can occur in people with the skin disease psoriasis; and

• Enteropathic arthritis/spondylitis, a form of chronic inflammatory arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Enteropathic arthritis may be designated as axial (low back pain due to ankylosing spondylitis) or peripheral (joint involvement).

While some patients with psoriatic arthritis have a spondyloarthritis, in others, the involvement is primarily in peripheral joints. Psoriatic arthritis can resemble RA, but tests for rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP will be negative.

Prevalence of Spondylarthropathies

The prevalence of SpA in the US is difficult to determine as the diseases affect ethnic groups differently. Estimates of prevalence for SpA are 0.01%-2.5%.1,2 Current estimates of prevalence of the more common diseases are:

• Ankylosing spondylitis, 0.2%-1.7%1,2,3,4

o Axial SpA, 0.9%-1.4%2,3,4,5,6

o Advanced AS, 0.52%-0.55%2

• Psoriatic arthritis, 0.1%-0.4%1

• Reactive arthritis, no estimate found

• Enteropathic peripheral arthritis, 0.065%1

• Enteropathic axial arthritis, 0.05%-0.25%.1

Healthcare Utilization

Spondyloarthropathy was diagnosed in about one-half million hospitalizations in 2013, representing 1.6% of hospital discharges for all diagnoses, a higher proportion than prevalence in the population (1.6% of discharges vs 1.0%). No differences were found by sex, race/ethnicity, or geographic region, but age was a factor in the rate of hospitalizations for SpA. (Table 3A.3.1.0.1 PDF [35] CSV [36]; Table 3A.3.1.0.2 PDF [37] CSV [38]; Table 3A.3.1.0.3 PDF [39] CSV [40]; Table 3A.3.1.0.4 PDF [41] CSV [42])

Among those with a diagnosis of SpA, hospital discharge rates showed higher mean charges ($60,000 per SpA discharge versus $43,000 for any diagnoses) for a similar mean length of stay (4.6 days versus 4.7 days). Discharges from the hospital to additional care (short-term or home health) was slightly higher for persons with a diagnois of SpA (40%) than for all diagnoses discharges (31%). (Reference Table 3A.3.1.1.1 PDF [27] CSV [28]; Table 3A.3.1.3.1 PDF [29] CSV [30])

Spondylarthropathies accounted for 0.7% of all diagnoses ambulatory care visits. Males were slightly more likely (0.8%) to receive ambulatory health care for SpA than females, along with those age 45 to 64 years (1.0%) and those living in the South (0.9%). (Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.1 PDF [43] CSV [44]; Table 3A.3.2.0.2 PDF [45] CSV [46]; Table 3A.3.2.0.3 PDF [47] CSV [48]; Table 3A.3.2.0.4 PDF [49] CSV [50])

Economic Burden

Economic burden was not calculated by the BMUS project for spondyloarthropathies due to sample sizes. One study cited mean annual direct medical costs for AS of $6,500.7

Several published studies have explored the medication cost of biologics. For AS, biologic cost ranged from $1,200 to $24,200; for PSA ranged $14,200 to $32,000.7,8,9

Connective tissue disorders (CTDs) are part of the systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases (SARD) grouping of disorders and include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE or lupus), systemic sclerosis (SSc or scleroderma), inflammatory myositis (polymyositis and dermatomyositis), and Sjögren syndrome (SjS). They are characterized by a heterogeneous group of immune-mediated inflammatory signs and symptoms affecting multiple organ systems, including the joints.

Prevalence of Connective Tissue Disorders

The prevalence of syndromes in the CTD family are difficult to identify, and vary depending on the study duration, classification criteria, and the country in which the study was undertaken. Current estimates are based on special populations and primarily use several CDC-funded state registries. Connective tissue disorders affect all ages, but incidence is higher among women than men by a factor of at least 4:1, with estimates as high as 12:1 for SLE.1,2 Lupus generally begins during women’s children bearing years and can lead to serious kidney involvement among other complications.

The highest prevalence is for SjS, ranging between 0.5% and 3% of a given demographic population.1 Estimates of overall prevalence range from 400,000 to 3.1 million US adults.3

Recent national estimates of prevalence and incidence of SLE in the US are not available, but it is relatively uncommon. Using older meta-analysis studies, prevalence of SLE is estimated between 15 and 50 per 100,000 individuals.1 The Lupus Foundation of America estimates a total of 1.5 million Americans have some form of lupus, with an incidence of 16,000 new cases per year.4

The prevalence of SSc, also known as scleroderma, is much lower and has been reported with an incidence of 20 per one million new cases per year and a prevalence of 240 per million US adults, based on a limited US population studies published in 2003.5,6 A more recent update did not find this estimate to be changed.7

Overall prevalence and incidence of CTD is not reported in the literature, as classification criteria are not defined.1 However, the economic analysis for this report places prevalence at 0.27% for the years 2008 thru 2014. (Reference Table 8.20 PDF [91] CSV [92])

Healthcare Utilization

Connective tissue disorders represented 1% of hospital discharges and total charges for all diagnoses hospital stays in 2013. Because of the very low incidence of CTD syndromes, the prevalence is estimated at 0.3 percent or less, with use of healthcare resources much higher than the incidence ratio. Although the share of hospital discharges is higher than the share of all ambulatory visits, the rate of hospital discharges per 100 adults is much lower than the rate of ambulatory visits. Mean length of hospital stay and mean hospital charges are slightly higher than the means for all diagnoses, but patients are generally discharged to home self-care. (Reference Table 3A.3.1.0.1 PDF [35] CSV [36]; Table 3A.3.2.0.1 PDF [43] CSV [44]; Table 3A.3.1.1.1 PDF [27] CSV [28]; Table 3A.3.1.3.1 PDF [29] CSV [30])

Hospitalizations for CTDs occurred primarily in females, those age 45-64 years, and non-Hispanic blacks compared to all diagnoses discharges. (Table 3A.3.1.0.1 PDF [35] CSV [36]; Table 3A.3.1.0.2 PDF [37] CSV [38]; Table 3A.3.1.0.3 PDF [39] CSV [40]; Table 3A.3.1.0.4 PDF [95] CSV [42])

Connective tissue disorders accounted for 0.4% of all diagnoses for ambulatory care visits. The distribution of ambulatory care visits by select demographic characteristics, when compared to all ambulatory visits for CTDs, was highest among females and non-Hispanic blacks, and lowest among those aged 65 years and older and those living in the Midwest. Females accounted for nearly all ambulatory CTD visits. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.1 PDF [43] CSV [44]; Table 3A.3.2.0.2 PDF [45] CSV [46]; Table 3A.3.2.0.3 PDF [47] CSV [48]; Table 3A.3.2.0.4 PDF [98] CSV [50])

Data from the MEPS, used exclusively in the economic analysis of this report, show higher levels of healthcare visits than the NIS and NAMCS. In particular, the number of ambulatory physician visits is much higher in the MEPS than in the NAMCS. Differences in how conditions are classified and data coded account for some of this, as does the inclusion of ambulatory visits in settings outside a physician’s office (eg, ER or outpatient clinic).

Based on the MEPS, most individuals with a CTD (93%) incurred one or more ambulatory physician visits; among all of those with CTD, the total number of ambulatory physician visits was 9.3 million visits (average visits per person=11.2) annually. Approximately two-thirds (67.9%) of those with CTDs had at least one non-physician care visit, which include physical therapists and alternative care. The average number of non-physician visits per person was 8.5, for a total of 7.0 million non-physician visits nationally. One in five (20.7%) individuals with a CTD were hospitalized and there were 300,000 hospitalizations among all people with CTDs, with an average of 0.4 hospitalizations per person. The percentage with home health care visits was lower (14.4%) than for the other types of visits. However, those with a CTD had an average of 17.1 home health care visits per year for a total of 14.2 million visits nationally. Furthermore, those who did have a home health visit had very high home health visit utilization, with an average of 119 visits annually (data not shown). Finally, almost all individuals with a a CTD filled a prescription medication (95.8%); the total number of prescription fills each year was 39.5 million, based on average prescription fills among all of those with CTD of 47.7 fills. (Reference Table 8.20 PDF [91] CSV [92])

Economic Burden

From 2008-2014, an estimated 800,000 individuals (0.27%) in the US population had a CTD annually. Across all age groups, middle age adults (45-64 years) represented the largest percentage of those with a CTD (52% or 430,000), followed by younger adults (18-44 years) (26% or 219,000 individuals), older adults (≥ 65 years) (21% or 173,000) and children (18 years) (1% or 8,000 individuals). These numbers translate into prevalence rates shown in the graph below. (Reference Table 8.19 PDF [101] CSV [102]; Table 8.21 PDF [103] CSV [104])

Females comprised the majority of those with a CTD (767,000); at least 400,000 individuals in the following groups had a CTD: those with any limitation in IADLS, ADLs, functioning, work, housework, school, vision, or hearing (597,000); non-Hispanic Whites (542,000); those with any private insurance (503,000); and those with any limitation in work, housework, or school activities (453,000). (Reference Table 8.21 PDF [103] CSV [104])

Among all individuals with a CTD, ambulatory care represented 32% of all direct costs, followed by inpatient care (28%), prescriptions (25%), and residual costs (15%). The distribution across service category varied substantially across socio-demographic and health status characteristics suggesting very different treatment and utilization patterns across these groups. For example, there were regional differences: among those in the Northeast, ambulatory care, inpatient care, prescriptions, and other costs represented 40%, 11%, 21%, and 28%, respectively whereas in the Midwest, these categories represented 25%, 24%, 44%, and 7% of all costs, respectively.

Among all individuals with a CTD, all-cause annual per person costs were $19,702. The five groups with the highest all-cause per person costs were those who were college graduates ($30,471), had public health insurance only ($29,579), lived in the Northeast ($27,349), had never married ($27,026), or reported any limitation in work, housework, or school activities ($27,024).

The five groups with the lowest all-cause per person costs were those with no health insurance ($5,631), lived in the Midwest ($11,821), were Non-Hispanic black ($14,564), had a high school education but no college education ($14,617), or were married/had a partner ($14,735). (Reference Table 8.21 PDF [103] CSV [104])

Indirect costs (earnings losses) were not calculated for CTDs due to small numbers of cases.

Gout is caused by a buildup in the body of uric acid, in the form of monosodium urate crystals that the body cannot rid itself of quickly. This condition is characterized by hyperuricemia, referring to an elevation in the serum level of uric acid. It is not fully understood why some people with hyperuricemia develop gout and others do not. Gout is characterized by recurrent attacks of painful, red, tender, warm, and swollen joints, which generally affects only one joint at a time, often the large toe. It is more common in men, but also affects women after menopause. Repeated flares of gout can lead to chronic gouty arthritis, with involvement of multiple joints and the development of subcutaneous nodules, called tophi. While gout can be an intermittent condition, it can also lead to severe chronic arthritis and joint damage and deformity. Gout occurs frequently in patients with what is termed the metabolic syndrome and affects patients who also have diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.

Other crystal arthropathies can be caused by deposits of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystals in the joints and have symptoms similar to gout. CPPD deposition disease is less common than gout, although radiographic chondrocalcinosis is common in older adults.

Prevalence of Gout

Prevalence estimates of gout vary for the US from 1% - 4%, depending on the data source and time frame. In 2005, an estimated 6.1 million adults reported having gout at some time, with 3.0 million affected each year.1 Estimates from the MEPS analyzed for the economic data section reported 3.1 million US adults had gout annually for the years 2008-2012, an annual prevalence rate of 1.3%.(Reference Table 8.13 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 8.24 PDF [114] CSV [115]) Additional studies report a higher prevalence of 3.9%, or 8.3 million adults in 2007-2008, using the NHANES as the basis of estimates.2,3,4 Another NHANES study from 2007-2010 reported a prevalence of 3.8%.5 Overall, it is believed the prevalence of gout is rising, with obesity and hypertension cited as contributors.2,4 A study of hospitalization trends using the NIS from 1993-2011 supported this, showing hospitalizations with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis declining over the study period while diagnosis of gout was reported as increasing.6

Prevalence of gout is higher in males than in females, 5.9% to 2.0%, respectively,4 or at a ratio of 3-4:1. The incidence of gout increases with age, and was shown in the MEPS to be higher in the following select socio-demographic groups: non-Hispanic whites (2.3 of 3.1 million); married/had a partner (1.9 million); any private insurance (2.0 million); those with any limitation in IADLs, ADLs, functioning, work, housework, school, vision, or hearing (1.7 million). (Reference Table 8.24 PDF [114] CSV [115]).

Healthcare Utilization

More than 850,000 hospitalizations in 2013 had a diagnosis of gout, representing 2.9% of hospitals visits for any diagnoses, and accounting for 3.3% of all hospital charges billed. Gout is diagnosed along with joint pain and soft tissue disorders when multiple diagnoses are made (7% and 3.5% cross-diagnosis, respectively). At discharge, patients diagnosed with gout are more likely to be transferred to short-term or home health care than those with any diagnoses (45% vs 31%). (Reference Table 3A.3.1.0.1 PDF [35] CSV [36]; Table 3A.3.0.2 PDF [116] CSV [117]; Table 3A.3.1.1.1 PDF [27] CSV [28]; Table 3A.3.1.3.1 PDF [29] CSV [30])

Gout diagnoses were made in only 0.5% of ambulatory care visits for any diagnosis, accounting for 5.3 million ambulatory visits. Ambulatory visits were made more frequently by males (72%), those aged 65 years and older (50%), non-Hispanic whites (59%), and by those living in the Northeast (rate of 2.8/100 persons versus 2.1/100 for all regions). (Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.1 PDF [43] CSV [44]; Table 3A.3.2.0.2 PDF [45] CSV [46]; Table 3A.3.2.0.3 PDF [47] CSV [48]; and Table 3A.3.2.0.4 PDF [49] CSV [50])

Economic Burden

Estimates for gout, defined as ICD-9-CM 274, were generated from 2008-2012 MEPS data; analysis was limited to those years because the ICD-9-CM code for gout was suppressed in 2013 and 2014 MEPS data. Combining direct and indirect costs for gout, total average costs annually for the years 2008-2012 were $26 billion. Incremental costs could not be calculated due to a small sample size. (Reference Table 8.13 PDF [11] CSV [12])

Among all adults with gout, all-cause per person direct costs were $11,936. Those with any limitation in work, housework, or school activities had the highest all-cause per person direct costs ($16,843) whereas those age 18-44 years had the lowest ($5,934). Total all-cause direct costs were $36.6 million. Direct costs attributable to gout were not reported because the relative standard errors for the estimates was greater than 30%. (Reference Table 8.13 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 8.24 PDF [114] CSV [115])

The percentage working during the year among adults age 18-64 years was similar for those with (85%) and without gout (88%). Per person, those with gout earned $6,810 more than those without gout; thus, overall, those with gout had negative earnings losses (aggregate of -10.0 billion). Like direct costs, earnings losses attributable to gout were not reported because the estimates were unreliable, with a relative standard error greater than 30%. (Reference Table 8.13 PDF [11] CSV [12]).

Arthritis from joint infection, known by the umbrella term as septic arthritis, can occur from an infection anywhere in the body traveling through the bloodstream. It can also occur from a penetrating injury that delivers germs directly to a joint. An infected joint is usually very tender, swollen, and painful. When caught early and treated with antibiotics it can be cleared of the joint infection. Surgical drainage of the infected joint is often necessary which can be performed arthroscopically. In some cases, the arthritis becomes chronic. Knees are most commonly affected, but septic arthritis also can affect hips, shoulders, and other joints. Often, an infected joint has been affected by another form of arthritis. Gonococcal septic arthritis, transmitted from gonorrhea bacterium, a sexually transmitted disease, can occur in otherwise healthy individuals. Lyme disease is another form of arthritis associated with infection and occurs in certain areas of the country.

The incidence of septic arthritis in industrialized countries, including the US, is estimated at six (2-10) per 100,000 population per year. In persons with underlying joint disease or prosthetic joints, incidence increases to 6-30 per 100,000 per year. The most susceptible populations are young children and the elderly.1 Infection can occur in a prosthetic joint and be a source of chronic pain. Biologics, while shown to work well for RA and other inflammatory arthritis pain, have also been associated with statistically significant higher rates of serious infections as they are designed to weaken the immune system. Serious infections included opportunistic infections as well as bacterial infections in most studies.2 These side effects of increased risk for septic arthritis are recognized and published in numerous sources.

Septic arthritis is included in the “other specific rheumatic conditions” in the AORC discussion.

Fibromyalgia does not fit within the main arthritis classifications but is considered a chronic pain condition. The primary symptoms are widespread pain throughout the body and fatigue. Recent revisions to diagnosis now focus on four criteria.1

1) Generalized pain, defined as pain in at least 4 of 5 regions is present.

2) Symptoms have been present at a similar level for at least 3 months.

3) Widespread pain index (WPI) ≥7 and symptom severity scale (SSS) score ≥5 OR WPI of 4-6 and SSS score ≥9.

4) A diagnosis of fibromyalgia is valid irrespective of other diagnoses. A diagnosis of fibromyalgia does not exclude the presence of other clinically important illnesses.

The cause of fibromyalgia is not known, but current theories include a higher sensitivity to pain. Fibromyalgia can occur by itself, although it can also accompany another form of arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis or spondyloarthritis.

Prevalence of Fibromyalgia

Estimates of fibromyalgia range from 4 million (2% of the adult population)2 to 10 million (5% of adult population).3 Fibromyalgia is most prevalent in females, with up to 90% of incident cases females. It is also more common among older members of the population.

Healthcare Utilization

Just under one-half million (442,000) hospitalizations in 2013 had a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, representing 1.5% of hospital visits for any diagnoses, and accounting for 1.4% of all hospital charges billed. Females accounted for 89% of the hospitalizations, with those age 45 to 64 accounting for nearly half (48%) of the discharges. Fibromyalgia is diagnosed along with connective tissue disease (11.1%), joint pain (8.2%), and rheumatoid arthritis (7.1%) when multiple diagnoses are made. Hospital stays are similar to discharges for any diagnoses in length of stay and mean charges. Discharge to home is most common. (Reference Table 3A.3.1.0.1 PDF [35] CSV [36]; Table 3A.3.1.0.2 PDF [37] CSV [38]; Table 3A.3.0.2 PDF [116] CSV [117]; Table 3A.3.1.1.1 PDF [27] CSV [28]; Table 3A.3.1.3.1 PDF [29] CSV [30])

Fibromyalgia diagnoses were made in 0.8% of all ambulatory care visits for any diagnosis, accounting for 7.7 million ambulatory visits. Ambulatory visits were made more frequently by females (79%), those aged 45-64 years (52%), non-Hispanic whites (74%), and by those living in the Northeast region (rate of 3.8/100 persons versus 3.1/100 for all regions). (Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.1 PDF [43] CSV [44]; Table 3A.3.2.0.2 PDF [45] CSV [46]; Table 3A.3.2.0.3 PDF [47] CSV [48]; and Table 3A.3.2.0.4 PDF [49] CSV [50])

Economic Burden

Economic costs were not calculated for fibromyalgia.

Juvenile arthritis (JA) is an umbrella term used to describe a number of autoimmune and inflammatory conditions that can develop in children. It is the most common rheumatic disease of childhood, particularly in the Western world, with children of European descent reporting higher incidence rates.1,2

The most common form of JA is Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) (formally called juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) or Juvenile Chronic Arthritis (JCA)). JIA is diagnosed in a child <16 years of age with at least six weeks of persistent arthritis. There are seven distinct subtypes, each having a different presentation and association to autoimmunity and genetics.3 Subtypes also differ in typical age of onset. Certain subtypes are associated with an increased risk of inflammatory eye disease (uveitis).

Understanding the differences in the various forms of JIA, their causes, and methods to better diagnose and treat these conditions in children is important to future treatment and prevention. Among all subtypes, 40% to 45% of children with JIA still have active disease after 10 years.4

Prevalence Of Juvenile Arthritis

Due to the various forms of JA, estimates of prevalence and incidence are difficult to ascertain. Overall estimates are that 294,000 children in the United States have arthritis or another rheumatic disease.5

In 2006, the CDC Arthritis Program finalized a case definition for ongoing surveillance of significant pediatric arthritis and other rheumatologic conditions (SPARC [130]) using the current ICD-9-CM diagnostically based data systems. In response to the variations in conditions that some felt should be included, but were not, CDC generated estimates for conditions that were not included in the case definition but were felt by some should have been.

Healthcare Utilization

Using the SPARC definitions, analysis of the recent national healthcare database focusing on children, the Healthcare Cost and Utility Project (HCUP) KID, showed 104,400 children age 17 and younger were discharged from a hospital with any diagnosis of SPARC in 2012. Of those, 15,600, or 15%, had an admitting diagnosis of SPARC. Slightly more females than males were hospitalized; children age 6 and younger were more likely to be hospitalized with an admitting diagnosis of SPARC than older children, accounting for 40% of admissions.

Only a small number of children (3.8%) discharged with any diagnosis of SPARC had a diagnosis of juvenile arthritis. Females accounted for 72% of discharges with a diagnosis of JIA, with 62% of the discharges for children age 13 to 17 years.

Average hospital stays of eight days were found for any diagnosis of SPARC. The very youngest children, babies under age one, had much longer stays and higher mean hospital charges. Children with a diagnosis of JIA had hospital stays of a mean of 4.6 days, with subsequently lower mean charges.

Total hospital charges associated with any diagnoses of SPARC in the population younger than age 20 were $8.3 billion in 2012. (Reference Table 3B.1 PDF [131] CSV [132])

Emergency rooms saw 515,600 patients ages 0 to 17 with any diagnoses of SPARC in 2013. Among these patients, 6,900 had a primary diagnosis of JIA. Visits did not show major differences by sex or age.

Due to smaller sample sizes in the currently available databases for physician office visits and outpatient clinics, outpatient visits for a diagnosis of SPARC in the juvenile population are difficult to quantify. In 2013, physician visits for treatment of JA numbered 1.2 million. As with ED visits, major differences by sex or age were not seen. Due to small sample sizes, the number of visits with a diagnosis of JIA was unreliable.

Outpatient clinics saw 305,100 patients in 2011, the most recent year for outpatient data available. Patterns for distribution reflected that of other treatment sites. Due to small sample sizes, the number of visits with a diagnosis of JIA was unreliable.

From these data, an estimated 2.03 million outpatient visits for any diagnoses of SPARC occurred in the 0 to 17 years age population in 2013. (Reference Table 3B.1 PDF [131] CSV [132])

ICD-9-CM Codes for SPARC

In 2006, the CDC Arthritis Program finalized a case definition for ongoing surveillance of significant pediatric arthritis and other rheumatologic conditions (SPARC) using the current ICD-9-CM diagnostically-based data systems.

099.3 - Reactive arthritis

136.1 - Behcet's syndrome

274 - Gout

277.3 - Amyloidosis (includes Familial Mediterranean Fever)

287.0 - Allergic purpura / Henoch Schonlein purpura

390 - Rheumatic fever without heart involvement

391 - Rheumatic fever with heart involvement

437.4 - Cerebral arteritis

443.0 - Raynaud's syndrome

446 - Polyarteritis nodosa and allied conditions

447.6 - Arteritis, unspecified

695.2 - Erythema nodosum

696.0 - Psoriatic arthropathy

701.0 - Linear scleroderma / Circumscribed scleroderma / Morphea

710 - Diffuse diseases of connective tissue

711 - Arthropathy associated with infections

712 - Crystal arthropathies

713 - Arthropathy associated with other disorders classified elsewhere

714 - Rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory polyarthropathies

715 - Osteoarthritis and allied disorders

716 - Other and unspecified arthropathies

719.2 - Villonodular synovitis

719.3 - Palindromic rheumatism

720 - Ankylosing spondylitis and other inflammatory spondylopathies

727.0 - Tenosynovitis

729.0 - Rheumatism, unspecified and fibrositis

729.1 - Myalgia and myositis, unspecified

Joint pain is a major symptom of arthritis and non-arthritis conditions and a primary reason for seeing a medical care provider. Self-report surveys ask about joint pain but do not distinguish the cause of joint pain, which may be from arthritis, injuries, or degeneration of bone surfaces.

In 2013-2015, chronic joint pain was self-reported in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) by 78.9 million adults, among which 40.2 million also reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis (DDA) and 29.1 million reported activity limitations due to arthritis (AAAL). Because the latter two groups are not mutually exclusive, 30.4 million, or about 13% of the total population, have chronic joint pain but no DDA or AAAL. (Reference Table 3A.2.0 PDF [139] CSV [140])

The most common site of chronic joint pain reported by adults with DDA is the knee, reported by nearly 1 in 2 adults. Pain in the shoulder, finger, and/or hip is reported at each site by more than 1 in 4 adults with DDA. While 40% of people with DDA report joint pain in only one site, more than 20% report pain in four or more sites. (Reference Table 3A.2.1.1 PDF [141] CSV [142] and Table 3A.2.1.5 PDF [143] CSV [144])

Among adults with DDA, joint pain occurs in females more frequently than males, and in middle age more frequently than younger or older ages. Joint pain was similar by race/ethnicity and region. (Reference Table 3A.2.1.1 PDF [141] CSV [142]; Table 3A.2.1.2 PDF [145] CSV [146]; Table 3A2.1.3; PDF [147] CSV [148]; and Table 3A.2.1.4 PDF [149] CSV [150])

Joint Replacement

While in some sense, the need for a joint replacement represents failure of measures to prevent the occurrence or progression of joint problems, for those with the severe pain or poor function of end-stage joint problems, it can offer a life-altering “cure.” Joint replacements represent one of the fastest growing procedures in the US. Joint replacement procedures for hips and knees are most common, but replacements have been expanding to other joint sites in recent years.

Estimates presented come from the Healthcare Cost and Utility Project (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). In previous editions of BMUS, estimates from the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) were also presented and are found in two tables showing trends on mean age of joint replacement patients and average length of hospital stay. The NHDS is no longer produced and not otherwise used here.

In 2013, an estimated 1.3 million inpatient joint replacement procedures were performed. Joint replacement procedures comprised about 3.6% of all inpatient procedures. More joint replacements were performed on women than men (60% vs 40%), and 95% of the procedures were performed on knees or hips. (Reference Table 3A.5.1.1 PDF [153] CSV [154])

In 2013, nearly 723,000 knee replacement procedures were performed in the U.S., comprising 56% of all joint replacement procedures. Over 90% were total knee replacements, but 8% were revision knee replacements, which occur when the original replacement fails or becomes infected. Three in five knee replacements (62%) occurred in females. More than one-half (57%) of knee replacement procedures were performed on those aged 65 years and older, but a substantial proportion (41%) were performed on persons aged 45 to 64 years. The majority (77%) of knee replacements were performed on non-Hispanic whites, with a proportion more than twice that of other racial/ethnic groups. The ratio of knee replacements to total population is higher in the Midwest region (27.2% of replacements vs. 21.4% of population) than other regions, with the Northeast having the lowest ratio of procedures (16.9% vs. 17.7%). (Reference Table 3A.5.1.1 PDF [153] CSV [154]; Table 3A.5.1.2 PDF [157] CSV [158]; Table 3A.5.1.3 PDF [159] CSV [160]; and Table 3A.5.1.4 PDF [161] CSV [162])

Trends in knee replacement procedures from 1992 to 2013 show steady increases in both total and revision knee replacements. Over the 22-year period, knee replacement procedures more than tripled, with the ratio of revisions to total remaining constant at 8% to 10%. (Reference Table 3A.5.2 PDF [163] CSV [164]).

The principal or first diagnosis associated with total knee replacement is osteoarthritis, accounting for 98% of all replacements in 2013. (Reference Table 3A.5.3 PDF [31] CSV [32]).

The 22-year mean age from 1992 to 2013 was nearly 68 years for total knee replacements, and about half a year younger for revision knee replacements. The mean age for both procedures shows a slow decline over time. (Reference Table 3A.5.4 PDF [167] CSV [168])

The average inpatient length of stay for total knee replacements has shown a remarkable decline of about 67% from a mean of nearly 8.9 days in 1992 to a mean of 3.4 days in 2013. (Reference Table 3A.5.5 PDF [169] CSV [170]).

Despite shorter hospital stays, the mean hospital charges from 1998 through 2013 showed a steady increase for all knee replacements, with revision knee replacement being more expensive than total knee replacement. Total hospitalization charges for both types of knee replacements have increased by five times over (in constant 2013 dollars) from $8.4 billion in 1998 to $41.7 billion in 2013. (Reference Table 3A.5.6 PDF [173] CSV [174])

Most adults (72%) with knee replacements are discharged to either short- or long-term care or home health care, likely due to the short hospital stay. Among persons aged 65 and older, a slightly higher proportion are discharged to either short- or long-term care or home health care (77%). (Reference Table 3A.5.7 PDF [177] CSV [178])

An estimated 493,700 hip replacement procedures were performed in 2013, comprising 39% of all joint replacement procedures. A majority, about 58%, occurred in females. Total hip replacements occurred three times as frequently as partial hip replacements, and both are far more common than revision hip replacement. A very small number of procedures, about 3,700 in 2013, were hip resurfacing, an alternative to replacement, particularly for young, active males. Females have more hip replacement procedures than males, particularly partial replacements. Hip replacements were more common among adults aged 65 years and older (61%), with most of the rest occurring among adults aged 45 to 64 years. Hip replacements by race/ethnicity paralleled that for all joint replacements, as did hip replacements by geographic region. (Reference Table 3A.5.1.1 PDF [153] CSV [154]; Table 3A.5.1.2 PDF [157] CSV [158]; Table 3A.5.1.3 PDF [159] CSV [160]; and Table 3A.5.1.4 PDF [161] CSV [162])

Trends in hip replacement procedures from 1992 to 2013 show total hip replacements increasing in number by 150%, while the number of partial replacements remained relatively stable. The ratio of revision hip to total hip replacements was about 20% from 1992 to 2002, but has consistently been around 17% since then, and dropped to 15% in 2013. (Reference Table 3A.5.2 PDF [163] CSV [164])

The principal or first listed diagnosis associated with total hip replacements was osteoarthritis (87%). The primary diagnosis for partial hip replacements was fractures (94%). (Reference Table 3A.5.3 PDF [31] CSV [32])

The 22-year mean age was about 66 years for total hip replacements and 77 years for partial hip replacements, reflecting the different underlying diagnoses. Mean ages for both procedures show a slight decline over the time period, reflecting the younger age at which joint replacements are now considered. However, in 2013, the mean age for partial hip replacements jumped to 80. (Reference Table 3A.5.4 PDF [167] CSV [168])

The mean length of stay for total hip replacements (3.0 days in 2013) showed the same remarkable decline as that for knee replacements--about 67% from 1992 through 2013. The mean lenth- of-stays for partial and revision replacements are longer, with about a 50% decline over the 22-year period. (Reference Table 3A.5.5 PDF [169] CSV [170])

Despite shorter hospital stays, mean hospital charges from 1998 through 2013 steadily increased for all hip replacements even when compared in constant 2013 dollars. Revision hip replacements are the most expensive, while total hip replacements are the least expensive. Total hospital charges for all hip replacements have tripled (in constant 2013 dollars) from $9.25 billion in 1998 to $30.7 billion in 2013, led by charges for total hip replacements. (Reference Table 3A.5.6 PDF [173] CSV [174])

Shoulder replacement procedures accounted for an estimated 45,000 procedures in 2013, comprising about 4% of all joint replacement procedures. At the same time, an estimated 19,000 other joint replacement procedures were performed for other joints in the upper and lower extremities, and the spine. More than with hip and knee replacements, these other joint replacement procedures occurred somewhat equally between females and males, and were more evenly divided between those aged 44 to 64 and those aged 65 years and older, except for shoulder replacements. Race/ethnicity and geographic regions resembled the distribution of all joint replacements. (Reference Table 3A.5.1.1 PDF [153] CSV [154]; Table 3A.5.1.2 PDF [157] CSV [158]; Table 3A.5.1.3 PDF [159] CSV [160]; and Table 3A.5.1.4 PDF [161] CSV [162])

A recent study released by the CDC Arthritis Workgroup1 reported state-level arthritis prevalence estimates for the first time. Using the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) self-reported doctor-diagnosed data, age-adjusted for comparison across states, the median prevalence among adults across the 50 states and District of Columbia was 23.0%. State prevalence ranged from 17.2% in Hawaii to 33.6% in West Virginia. When viewed by states in the four regions used in this report, 75% of states in the South had an age-adjusted prevalence rate above that of the national rate of 23.0%. This compares to 40% in the Northeast, 42% in the Midwest, and 31% in the West. Furthermore, five states in the South (West Virginia, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Arkansas) and two in the Midwest (Michigan and Missouri) had a majority of counties with an arthritis prevalence rate in the highest quartile (31.2%-42.7%). A summary of state age-adjusted doctor-diagnosed arthritis prevalence rates can be found by clicking HERE [187].

The study also looked at doctor-diagnosed arthritis prevalence among adults with three comorbid conditions. At 44.5%, prevalence of arthritis was highest among those with coronary heart disease. This was followed by adults with diabetes (37.3%) and obesity (30.9%).

Leisure-time physical inactivity was also analyzed, and the median age-standardized percentage of inactive adults with arthritis was 35.0%. States in the western region tended to have the lowest prevalence of leisure-time physical inactivity with arthritis, while states in Appalachia and along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers had the highest percentage of leisure-time physical inactivity, following the overall state prevalence rates for arthritis.

Findings from this study showed that estimated prevalence of arthritis varies by geographic area, with correlation to comorbid conditions and negative health-related characteristics. While direct causation cannot be made and further study is needed to understand why these geographic differences occur, the authors have postulated that known risk factors for arthritis such as comorbid conditions, occupation, socioeconomic status, and negative health-related characteristics may contribute. Access to medical care and medications may also be factors.

The full study of arthritis prevalence by state can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/data_statistics/state-data-current.htm [188].

The CDC has also produced estimates of arthritis prevalence by race/ethnicity2 based on the NHIS 2013-2015 data. The lowest prevalence rate was found among non-Hispanic Asians (11.8%), with non-Hispanic multi-racial adults having the highest rate (25.2%). Among adults with arthritis, non-Hispanic Asians also reported the lowest prevalence of arthritis-attributable activity limitations (37.6%), while American Indian/Alaska Natives reported the highest prevalence of limitations (51.5%).

While medical professionals in many specialities and with a range of credentials treat patients with arthritis, those specializing in rheumatology are often at the frontline. A recently published workforce study by the American College of Rheumatology highlighted significant disparities in access to care within geographic regions of the US. Their findings showed access to care (defined as the ratio of adult rheumatology physicians to adult population) to be easiest in the Northeast (26,677 ratio) and most difficult in the Southern states (66,163 in the Southwest and 60,087 in the Southeast). This compares to a national average of rheumatologists per population of 41,658.3 Comparing this finding to the number of hospitalization and ambulatory healthcare visits, the highest number of visits, or need for care, was in the South. Furthermore, the study cited above reported the highest arthritis prevalence in the South.

In addition to regional differences, access to care based on population size is also the norm, as patients in areas with less than 50,000 population often must travel 200 or more miles to see a rheumatologist. The ratio of pediatric rheumatologists is much higher (229,442 children/physician), and it is estimated that only one-quarter of those aged 18 or younger with juvenile arthritis are currently able to see a rheumatologist.3

There are many challenges to the management of patients with arthritis that need to be addressed in the future, including, but not limited to, access to specialty care for timely and accurate diagnosis, appropriate use of non-pharmacologic modailities and pharmacotherapy, including targeted small molecule and newer biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), adherence to pharmacotherapy, and addressing comorbid medical conditions in patients with various forms of arthritis.

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) conducted a workforce study in 2015 and noted that the demand for care of patients with arthritis would continue to increase with the aging of the US population.1 Major areas that were identified include the role of primary care providers in the diagnosis and management of common forms of arthritis (eg, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, gout) and strategies to improve options for access to rheumatologist specialty care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthritides, and systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Training of more mid-level providers (ie, nurse practitioners and physician assistants) and more health professionals (eg, nurses, physical therapists, and occupational therapists) in the care of patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases would work to address some of this demand.

In addition to issues regarding workforce, there are potential barriers to care including insurance coverage, high co-pays, and limits on number for visits for rehabilitation services such as physical therapy and occupational therapy. Adding to the cost of non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions, especially newer biologic DMARDS, and pharmacy benefit reimbursement plans, are barriers due to high co-pays and prior authorization required for newer pharmacologic interventions.

Funding of clinical trials to provide best evidence of the efficacy of treatment modalities, including non-pharmacologic interventions is needed. It is extremely important that evidence-based treatments be translated into clinical practice through the use of evidence-based recommendations published by nationally recognized professional societies. Such recommendations exist for the management of most forms of arthritis including, but not limited to, gout, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis (formerly known as ankylosing spondylitis), psoriatic arthritis, and fibromyalgia. These recommendations include the use of both non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic modalities; it is felt to be important to emphasize the role of the former approaches particularly for osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia.

Virtually all forms of arthritis and systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases are chronic conditions and effective treatments require patient participation, whether that is taking medications regularly (eg, urate-lowering therapy for gout) or making lifestyle changes such as adhering to dietary changes, a lifelong pattern of physical activity, or using cognitive behavioral therapy or mind-body techniques.

Patients with various forms of arthritis have an increased risk for cardiovascular comorbidities including coronary artery disease. While control of systemic inflammation appears to be important in ameliorating this risk, it is important for practitioners to focus on reducing other factors that contribute to increased cardiovascular disease risk including overweight and obesity, lack of physical activity, smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus. Depression also has been recognized as contributing to persistent pain, reduced physical function, and impaired quality of life in patients with various forms of arthritis. There is an ongoing need for care coordination between the rheumatology specialist and the primary care provider, particularly in patients who require co-management.

Meeting current and future needs will require a wealth of data currently not available or accessible. In the broad scope of musculoskeletal diseases, data currently either not available or inaccessible to BMUS analysts include treatment cost/benefits, medical workforce, geographic data at detail levels (due to small sample sizes), and outcomes.

In addition, many of the requests for additional data and analysis are beyond the scope of the current BMUS project due to staff size, staff expertise, and funding.

Major unmet needs for patients with arthritis include new, effective interventions for the safe treatment of chronic pain, improving insurance coverage for effective evidence-based, non-pharmacologic interventions, as well as newer, targeted small molecules, biologic DMARDs, and the development and approval of Disease Modifying Osteoarthritis Drugs (DMOADs) to slow or prevent progression of osteoarthritis.

Additionally, there is an ongoing need for research funding to understand the pathophysiology of the various forms of arthritis with the goal of estabilishing effective strategies for primary prevention, determining the appropriate timing for surgical intervention and the role of pre- and post-operative exercise programs to maximize functional recovery after surgical interventions, and understanding the underlying reasons for the observed sex/gender and race/ethnicity disparities in most forms of arthritis and systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases.

Meeting future patient care needs will require increasing the workforce size of medical professionals. The 2015 Workforce Study by the American College of Rheumatology reported an excess demand for adult rheumatology care givers over current workforce projections of nearly 3200 professionals by 2030 and an excess demand of nearly 200 professionals in pediatric rheumatology.1 Other specialists in the care of arthritis likely show similar workforce demands.

The use of ICD-9-CM codes for clinical and public health purposes ended with the implementation of ICD-10-CM codes effective October 1, 2015. Standard definitions of generic and specific types of arthritis need to be developed for clinical and public health researchers using the new ICD-10-CM codes.

The crosswalk presented HERE [194] is for informational purposes only and should be carefully reviewed before used in future analysis.

Links:

[1] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib10/osteoarthritis

[2] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib20/inflammatory-arthritis

[3] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib21/rheumatoid-arthritis

[4] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib22/spondyloarthropathies

[5] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib23/connective-tissue-disorders

[6] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib30/gout-0

[7] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib40/joint-infection

[8] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib50/fibromyalgia

[9] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib60/juvenile-arthritis

[10] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib70/joint-pain-and-joint-replacement

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.13.pdf

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.13.csv

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.22.pdf

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.22.csv

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c102png

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.1.0.2_0.png

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c101png

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.1.0.1_0.png

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.1.1.a.pdf

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.1.1.a.csv

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c101apng

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.1.0.1.a.png

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3c.1.0.pdf

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3c.1.0.csv

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.1.pdf

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.1.csv

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.1.1.pdf

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.1.1.csv

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.3.1.pdf

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.3.1.csv

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.5.3.pdf

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.5.3.csv

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c103png-0

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.1.0.3_1.png

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.1.pdf

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.1.csv

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.2.pdf

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.2.csv

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.3.pdf

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.3.csv

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.4.pdf

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.4.csv

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.1.pdf

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.1.csv

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.2.pdf

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.2.csv

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.3.pdf

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.3.csv

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.4.pdf

[50] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.4.csv

[51] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c105png

[52] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.1.0.5_0.png

[53] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c106png

[54] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.1.0.6_0.png

[55] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_Conditions%20Related%20to%20Inflammatory%20Arthritis.pdf

[56] https://www.nras.org.uk/the-das28-score

[57] https://www.rheumatology.org/Portals/0/Files/SDAI%20Form.pdf

[58] https://www.rheumatology.org/Portals/0/Files/CDAI%20Form.pdf

[59] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c211png

[60] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.1.1_0.png

[61] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c212png

[62] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.1.2_0.png

[63] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c213png

[64] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.1.3_0.png

[65] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.1.1.pdf

[66] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.1.1.csv

[67] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.2.1.pdf

[68] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.2.1.csv

[69] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.3.1.pdf

[70] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.3.1.csv

[71] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c214png

[72] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.1.4_1.png

[73] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c215png

[74] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.1.5_0.png

[75] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c216png

[76] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.1.6_0.png

[77] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.23.pdf

[78] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.23.csv

[79] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c217png

[80] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.1.7_0.png

[81] https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k1036

[82] https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1036

[83] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c221png

[84] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.2.1_0.png

[85] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c222png

[86] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.2.2_0.png

[87] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4470267/

[88] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23436774

[89] http://dx.doi.org/10.7812/TPP/15-151

[90] https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Spondyloarthritis

[91] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.20.pdf

[92] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.20.csv

[93] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c231png

[94] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.3.1_0.png

[95] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.4pdf

[96] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c232png

[97] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.3.2_0.png

[98] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.4pdf

[99] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c233png

[100] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.3.3_0.png

[101] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.19.pdf

[102] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.19.csv

[103] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.21.pdf

[104] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.21.csv

[105] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c234png

[106] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.3.4_0.png

[107] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c235png

[108] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.3.5_0.png

[109] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3c236png

[110] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3c.2.3.6_0.png

[111] https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kel282

[112] https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases