[5]

[5]

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this chapter are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions (AORC) comprise over 100 diseases. What most of them have in common is that they cause pain, aching, stiffness or swelling in or around a joint.

Definitions

Defining AORC to assess the burden in a population requires considering both what is important to measure and what data sources are available, such as population surveys and administrative data. Complicating any definition is the 100+ conditions that comprise what is generally thought of as “arthritis.” Furthermore, population measures need to be relatively simple and perhaps different from definitions used in clinical practice, where there is the luxury of having a medical history, physical examination, and laboratory and radiographic data. The Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) Arthritis Program has worked with other organizations to develop case definitions, based on the best available expertise, that allow many measures of population burden to be addressed in a consistent way.1

For self-reported population surveys, doctor-diagnosed arthritis (DDA) is defined as a “yes” answer to the question “Have you EVER been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia?” This measure aims to capture most of the major categories of arthritis and is considered valid for surveillance purposes of estimating population prevalence.2 For data sources using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, arthritis and other rheumatic conditions (AORC) has been defined by the National Arthritis Data Workgroup using those codes, and further divided into ten more specific subcategories defined in Arthritis and Joint Pain Codes. Both definitions were designed to exclude or minimize other major categories of musculoskeletal disease, such as osteoporosis and generic chronic back pain, even though some chronic back pain is due to arthritis. DDA is likely better for estimating what is happening in the population at large because arthritis may not be mentioned or recorded at healthcare system encounters that are typically more focused on other conditions (e.g., diabetes, heart disease). However, even with the latter limitation, AORC is likely better for estimating what is happening in the healthcare system.

A recent review of relevant data sources considers the strengths and limitations of each of the different case definitions. Using DDA criteria, four databases defined prevalence within 3 percentage points, while using ICD-9-CM criteria they had a 5 percentage point spread. This study highlights the difficulty of applying a single number for estimating prevalence of AORC and the need to consider the purpose, design, measurement methods, and statistical precision of the data source being used.3

While AORC occurs in children, it is difficult to acquire population data on them, so most of the estimates presented in this report are for adults unless otherwise noted.

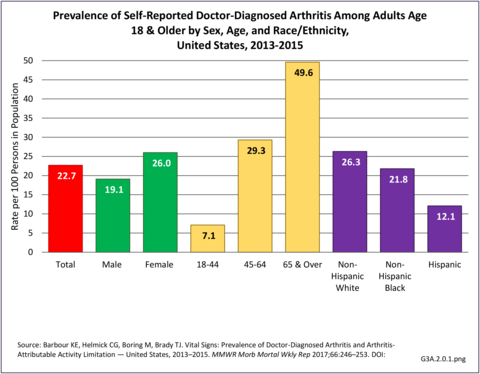

In the general population, prevalence is better estimated by DDA than AORC. For the years 2013-2015, DDA affected an unadjusted average of 54.4 million adults, or 23 in 100 adults.1 Estimates show the typical distribution of higher prevalence among females and older adults, and lower prevalence among Hispanics and Asians. Absolute estimates show that most of these adults (59%, or 32.2 million) are of working age (younger than age 65).1 (Reference Table 3A.1.1 PDF [2] CSV [3])

Specific types of AORC

Clinical data are required to provide some measure of validity for estimating the prevalence of specific types of arthritis because many people are not sure what type of arthritis they have. Data from the National Arthritis Data Workgroup provided 2005 national prevalence estimates for some of the ten specific types of arthritis used in later tables.2,3 Respondents could have reported more than one type.

Osteoarthritis: Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common type of arthritis, characterized by progressive damage to cartilage and other joint tissues. Joint injury is a risk factor for OA, but most cases occur without a specific history of injury. Obesity is a risk factor for knee OA, and to a lesser extent for hip and hand OA. Clinical OA was estimated to affect 26.9 million in 20053 and over 30 million for 2008-2011.4 The joints most affected with radiographic OA and symptomatic OA were hands, knees, and hips.3

Rheumatoid arthritis: Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the prototypical inflammatory arthritis. It is a chronic autoimmune disease that causes pain, aching, stiffness, and swelling in multiple joints, especially the hands, in a symmetrical fashion. In 2005, RA was estimated to affect 1.3 million adults.2

Gout and other crystal arthropathies: Gout is a recurrent inflammatory arthritis that occurs when excess uric acid collects in the body. Gout has been recognized for centuries and often affects the big toe. In 2005, an estimated 6.1 million adults reported having gout at some time, with 3.0 million affected in the past year.3 More recent studies of self-reported gout and hospitalizations show the prevalence of gout increasing in the last two decades.5,6

Joint pain/effusion/other unspecified joint disorders: Joint pain can result from several causes, including inflammation, degeneration, crystal deposition, infection, and trauma. Joint pain is often accompanied by swelling and effusion. A joint effusion is the presence of increased intra-articular fluid within the synovial compartment of a joint. Determining the cause of joint pain is primary to treatment.

Spondylarthropathies: Spondylarthropathies (or spondylarthritides) are a family of diseases that includes ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, enteropathic arthritis (associated with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease), juvenile spondylarthritis, and undifferentiated spondylarthritis. In 2005, spondylarthropathies affected an estimated 639,000 to 2.4 million adults ages 25 and older.2

Fibromyalgia: Fibromyalgia (FM) is a syndrome of widespread pain and tenderness. The diagnosis is difficult to make, so relevant prevalence data are hard to come by. In 2005, FM was estimated to affect around 5 million adults.3 A more recent estimate by the National Fibromyalgia Association puts the estimate at 10 million people in the US, with 75%-90% of the affected adult women. However, due to the difficulty in diagnosing fibromyalgia and the potential for including other causes of pain, this estimate should be used with caution.7

Diffuse connective tissue diseases include the next four diseases.

Systemic lupus erythematosus: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the prototypical autoimmune disease in which the body’s immune system can attack many body systems, especially the skin, kidneys, and joints. In 2005, definite and suspected SLE was conservatively estimated to affect 322,000.2 Population-based registries have provided more recent estimates for various racial/ethnic groups.8,9,10

Systemic Sclerosis: Systemic sclerosis (SSc), or scleroderma, is an autoimmune disease that primarily affects the skin, but can affect any organ system. In 2005, SSc affected an estimated 49,000 adults.2

Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome (SS) is a syndrome of dry eyes, dry mouth, and arthritis. Secondary SS can occur in association with other rheumatologic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Prevalence data are very limited. In 2005, an estimated 0.4 to 3.1 million adults had SS.2

Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell (temporal) arteritis: Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is a syndrome of sudden aching and stiffness in older adults that responds to treatment with anti-inflammatory medications (e.g., corticosteroids). Giant cell arteritis (GCA), which often occurs with PMR, is a type of vasculitis that affects medium-size arteries and results in headache, vision loss, and other symptoms. In 2005, PMR was estimated to affect 711,000 adults;3 a more recent analysis from the same data source found that the incidence of PMR had increased slightly with mortality not unlike the general population,11 suggesting that prevalence may have increased slightly as well. In 2005, GCA was estimated to affect 228,000 adults.4

Carpal tunnel syndrome: Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) occurs when the median nerve becomes compressed at the wrist and causes numbness, pain, or weakness in part of the hand. Thickened tendons and other rheumatic conditions are a common cause. General population prevalence has been reported between 1% and 5%.12

Soft tissue disorders (excluding back): These are a variety of problems of the tendons, bursa, muscle, ligaments, and fascia that cause pain and dysfunction. Prevalence of soft tissue disorders is difficult to determine due to the variety of conditions included.

Other specific rheumatic conditions: These are other conditions that the National Arthritis Data Workgrop considered to be rheumatic conditions.

Juvenile arthritis: Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions are relatively uncommon in children, although they can be particularly severe when they do occur. One estimate using significant pediatric arthritis and other rheumatologic conditions (SPARC) codes put the average annual prevalence at 103,000 children for the years 2001-2004 for the combined codes for rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory polyarthropathies, allergic purpura, arthropathy associated with infections, other and unspecified arthropathies, polyarteritis nodosa and allied conditions, and rarer inflammatory conditions.The prevalence for all SPARC codes, including synovitis and myalgia, was 294,000.13 A more in-depth discussion can be found in the Juvenile Arthritis (click HERE [6] to open new page) section later in this document.

AORC prevalence continues to increase in the aging US population, with related increases in healthcare utilization. The increase in total ambulatory care visits, together with the increasing number of joint replacements and related hospitalizations, both impact healthcare utilization. The AORC case definition is more appropriate to use within the healthcare system, which is based on health condition codes. However, the AORC case definition will miss adults with mild arthritis that is not mentioned at the visit, or for whom arthritis may not be a priority when multiple conditions are present. For estimates in the following discussions, AORC condition codes, found in ICD-9-CM Codes [8] section are used.

In 2013, AORC-related diagnoses were listed in 105.7 million healthcare visits and represented more than 10% of all healthcare visits. Hospitalizations accounted for 6% of AORC visits, while ambulatory care accounted for 94% (77% physician office, 6% outpatient, and 11% emergency department). (Reference Table 3A.3.0.1 PDF [9] CSV [10])

When looking at how the ten subtypes of AORC affect the four types of healthcare utilization below, remember that the estimates are not mutually exclusive due to the potential for multiple diagnoses in a single visit. (Reference Table 3A.3.0.2 PDF [13] CSV [14]; Table 3A3.0.3 PDF [15] CSV [16]; Table 3A.3.0.4 PDF [17] CSV [18]; and Table 3A.3.0.5 PDF [19] CSV [20])

Hospitalizations

The Healthcare Cost and Utility Project (HCUP) 2013 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) estimates that 6.4 million hospitalizations were associated with a diagnosis of AORC, or 21.4% of all hospitalizations that year. AORC was the presenting or first-listed diagnosis for only 1% of all hospitalizations, suggesting the role of AORC is more of an important comorbidity or contributor to other conditions which are the reason for the hospitalization. Nearly one-half of the 6.4 million AORC hospitalizations were associated with osteoarthritis (46%), while joint pain/effusion/other unspecified joint disorders, gout, and soft tissue disorders were each listed in more than 10% of hospitalizations. Multiple AORC diagnoses are coded in 17% of hospitalizations with an AORC diagnosis. Osteosteoarthritisrthritis is the least likely to have another AORC diagnosis, while carpal tunnel syndrome is most likely to include multiple diagnoses. (Reference Table 3A.3.0.1 PDF [9] CSV [10] and Table 3A.3.0.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

AORC-associated hospitalizations by sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region resembled those for all 2013 hospitalizations; however, they differed in age, skewing toward the 65 & older age group (59.1% vs. 41.7%). (Reference Table 3A.3.1.0.1 PDF [21] CSV [22]; Table 3A.3.1.0.2 PDF [23] CSV [24]; Table 3A.3.1.0.3 PDF [25] CSV [26]; Table 3A.3.1.0.4 PDF [27] CSV [28])

Hospitalizations for specific types of AORC differed by demographic variables. Women comprised 59% of total AORC hospitalizations, but much more for hospitalizations with rheumatoid arthritis (75%), fibromyalgia (89%), and diffuse connective tissue disease (87%). Men comprised 41% of total AORC hospitalizations, but much more for hospitalizations with gout (67%) and soft tissue disorders (52%). (Reference Table 3A.3.1.0.1 PDF [21] CSV [22])

Those younger than age 65 comprised 41% of total AORC hospitalizations, but much more for hospitalizations with fibromyalgia (68%), diffuse connective tissues disease (67%), and carpal tunnel syndrome (61%). (Reference Table 3A.3.1.0.2 PDF [23] CSV [24])

Non-Hispanic blacks comprised 12% of total AORC hospitalizations, but much more for hospitalizations with gout (18%) and diffuse connective tissue disease (24%). (Reference Table 3A.3.1.0.3 PDF [25] CSV [26])

Hospitalizations for specific types of AORC did not differ much by geographic region. (Reference Table 3A.3.1.0.4 PDF [27] CSV [28])

The mean LOS for AORC-associated hospitalizations in 2013 was slightly greater than that for all hospitalizations (4.9 vs 4.7 days); differences by demographic groups were greater for AORC hospitalizations (than all hospitalizations) for women (4.8 vs 4.4 days), those 18 to 44 years (5.0 vs. 3.6 days), non-Hispanic blacks (5.6 vs 4.4 days), Hispanics (5.3 vs. 3.6 days), and those in the western geographic region (4.8 vs. 4.3 days). Among the 10 specific types of AORC the mean LOS was strikingly longer for those with soft tissue disorders and other specified rheumatic conditions both overall (6.5 and 6.5 vs. 4.9 days) and by every demographic subgroup. (Reference Table 3A.3.1.1.1 PDF [33] CSV [34]; Table 3A.3.1.1.2 PDF [35] CSV [36]; Table 3A.3.1.1.3 PDF [37] CSV [38]; Table 3A.3.1.1.4 PDF [39] CSV [40])

Hospital charges are based on individual record discharges. The fees included may vary from patient to patient, but generally include hospital room, supplies, medications, laboratory fees, and care staff, such as nurses. They generally do not include professional fees (doctors) and non-covered charges. Emergency charges incurred prior to admission to the hospital may be included in total charges. It is important to note that charges are not necessarily the actual amount paid by Medicare, insurers, or patients. However, they are the only medical expenditure cost available in the major databases based on ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes and provide an overall picture for comparison purposes. Because multiple diagnoses are often made with an admission, actual charges related to a specific AORC may be much smaller. This is true of cost estimates provided in the Economic Burden [43] section also.

Mean hospital charges for AORC-associated hospitalizations generally paralleled, but were consistently higher than charges for all hospitalizations, both overall (+$5,900) and for all demographic subgroups. Higher mean charges among demographic subgroups were most striking for women (+$8,200), persons 18-44 years (+$18,800), non-Hispanic whites (+$9,900), non-Hispanic blacks (+$10,900), Hispanics (+$33,700), other non-Hispanics (+$10,700), and those in the South (+$9,500) and West (+$16,100).

Total charges for AORC-associated hospitalizations were $310.9 billion in 2013, comprising 24% of all hospital charges for the year. This percentage was relatively consistent for all sex and age groups except those 18 to 44 years, where it was only 11%. Among racial/ethnic groups, AORC total charges were 19% for non-Hispanic others, while they were 30% among non-Hispanic whites. AORC-associated hospitalization total charges were 29% of all hospitalizations in the Midwest in 2013.

Among the 10 AORC subgroups, hospitalizations with osteoarthritis accounted for $138.4 billion, or 45% of total charges for AORC-associated hospitalizations, while hospitalizations with joint pain/effusion/other, gout, and soft tissue disorders accounted for 16%, 13%, and 13% respectively). (Reference Table 3A.3.1.1.1 PDF [33] CSV [34]; Table 3A.3.1.1.2 PDF [35] CSV [36]; Table 3A.3.1.1.3 PDF [37] CSV [38]; Table 3A.3.1.1.4 PDF [39] CSV [40])

Discharge from the hospital to long-term care, which includes skilled nursing facilities, intermediate care, and other similar facilities, or to home health care occurred more frequently among AORC-associated hospitalizations than among all hospitalizations (44% vs 29%). This was true regardless of sex, age, race/ethnicity, or region of residence. By demographic characteristics, the highest proportion of discharge to long-term care or home health care was found among females (48%), age 65 and over (55%), and residents of the Northeast region (52%).

Among the 10 AORC subgroups there were no striking differences in discharge to long-term care or home health care compared with all AORC hospitalizations. Discharge to home was more frequent, and resembled all hospitalizations (66%), among those with carpal tunnel syndrome (68%), fibromyalgia (67%), diffuse connective tissue disease (64%), and spondylarthropathies (59%). (Reference Table 3A.3.1.3.1 PDF [46] CSV [47]; Table 3A.3.1.3.2 PDF [48] CSV [49]; Table 3A.3.1.3.3 PDF [50] CSV [51];Table 3A.3.1.3.4 PDF [52] CSV [53])

Ambulatory Care Visits

From the 2013 surveys on ambulatory care, there were an estimated 99.3 million ambulatory care visits associated with a diagnosis of AORC, more than 10% of all ambulatory care visits that year, for a rate of 40.1/100 adults in the general population. An AORC-related condition was listed as the presenting (first) diagnosis for between 2.8% and 5.4% of all ambulatory care visits, depending on the healthcare site visited. Physicians’ offices accounted for 82% of all ambulatory AORC visits, vastly exceeding emergency department (12%) or outpatient (7%) sites. (see Table 3A.3.0.1 PDF [9] CSV [10]) As with hospital discharges, multiple AORC diagnoses were given in 15% to 20% of patient ambulatory visits. (Reference Table 3A.3.0.3 PDF [15] CSV [16]; Table 3A.3.0.4 PDF [17] CSV [18]; and Table 3A.3.0.5 PDF [19] CSV [20])

In 2013, AORC-associated ambulatory care visits resembled all 2013 ambulatory care visits by sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region; they differed in age, being lower in the 18 to 44-year age group (21% vs. 32%) and higher in the 45 to 64-year age group (44% vs. 36%) and the 65 and older age group (34% vs. 32%). (Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.1 PDF [56] CSV [57]; Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.2 PDF [58] CSV [59]; Table 3A.3.2.0.3 PDF [60] CSV [61]; Table 3A.3.2.0.4 PDF [62] CSV [63]) (Note: Detailed data by type of ambulatory setting shown in Tables 3A.3.2.1.x, 3A.3.2.2.x(.1 to .4), and 3A.3.2.3.x, and can be accessed from the “Tables” tab in the upper right corner.)

Among the 10 AORC subgroups, 2 in 5 of the 99.3 million total ambulatory visits (41%) were associated with joint pain/effusion/other unspecified joint disorders or “other specified rheumatic conditions”; osteosteoarthritisrthritis and soft tissue disorders were the most common specific condition (~20% each). (Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.1 PDF [56] CSV [57])

AORC-associated ambulatory care visits for specific types of AORC differed by demographic variables. Women comprised 62% of all AORC-associated ambulatory care visits; their proportion was much higher for fibromyalgia (79%) and diffuse connective tissue disease (90%), but much lower for gout and other crystal arthropathies (27%). Men comprised 39% of all AORC-associated ambulatory care visits; their proportion was much higher for gout (72%). (Reference Table 3A3.2.0.1 PDF [56] CSV [57])

The 18 to 44-year old group comprised 21% of all AORC-associated ambulatory care visits; their proportion was a bit higher for diffuse connective tissue disease (31%), fibromyalgia (27%), and carpal tunnel syndrome (26%). Those aged 45 to 64 years comprised 44% of all AORC –associated ambulatory care visits; this proportion was similar for most specific types of AORC. Those aged 65 and older comprised 34% of all AORC-associated ambulatory care visits; their proportion was much higher for osteoarthritis (51%) and gout (50%), and much lower for fibromyalgia (20%). (Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.2 PDF [58] CSV [59])

Non-Hispanic whites (65% of the US population) comprised 73% of all AORC-associated ambulatory care visits, but only 59% of those for gout. Comparisons for other race/ethnic groups, as well as geographic regions were difficult to determine due to small sample sizes and unreliable data. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.0.3 PDF [15] CSV [16]; Table 3A.3.0.4 PDF [17] CSV [18])

Some 81 million AORC-related ambulatory care visits were physician office visits (PHYS); these accounted for 82% of all ambulatory care visits. An AORC-related condition was listed as the presenting (first) diagnosis for 5.4% of all PHYS visits. (Reference Table 3A.3.0.1 PDF [9] CSV [10])

Overall, 2013 AORC-related PHYS visits resembled those for all 2013 PHYS visits by sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region; they differed in age, being lower in the 18 to 44-year age group (20% vs. 29%), higher in the 45 to 64-year age group (46% vs. 37%), and similar in the 65 and older age group (34%).

Among the 10 AORC subgroups, nearly 2 in 5 of the 81 million AORC-related PHYS visits (37%) were associated with joint pain/effusion/other unspecified joint disorders; osteoarthritis and soft tissue disorders were about 21% each. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.1.1 PDF [72] CSV [73])

AORC-related PHYS visits for specific types of AORC differed by demographic variables. Women comprised 61% of all AORC-associated PHYS visits; their proportion was much higher for rheumatoid arthritis (77%) and diffuse connective tissue disease (90%). Men comprised 39% of all AORC-associated PHYS visits; their proportion was much higher for gout (71%). (Reference Table 3A.3.2.1.1 PDF [72] CSV [73])

Persons aged 18 to 44 comprised 20% of all AORC-associated PHYS visits; their proportion was higher for diffuse connective tissue disease (29%) and soft tissue disorders (26%), while lower for osteoarthritis (7%) and rheumatoid arthritis (13%). Those aged 45 to 64 comprised 46% of all AORC–associated PHYS visits; their proportion pf PHYS visits was higher for fibromyalgia (55%) and carpal tunnel syndrome (50%). Those aged 65 and older comprised 34% of all AORC-associated PHYS visits; their proportion was much higher for osteoarthritis (51%) (Reference Table 3A.3.2.1.2 PDF [74] CSV [75]).

Non-Hispanic whites comprised 74% of all AORC-associated PHYS visits; their proportion was higher for rheumatoid arthritis (80%), spondylarthropathies (79%), and lower for gout (65%) and carpal tunnel syndrome (68%). Comparisons for other race/ethnic groups were difficult to determine. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.1.3 PDF [76] CSV [77])

There was little difference by geographic region. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.1.4 PDF [78] CSV [79]).

Some 6.5 million AORC-related ambulatory care visits were to outpatient (OP) clinics; these accounted for 7% of all ambulatory care visits. An AORC-related condition was listed as the presenting (first) diagnosis for 4.4% of all OP visits. (Reference Table 3A.3.0.1 PDF CSV)2013 AORC-related OP visits resembled those for all 2013 OP visits by sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region; they differed in age, being lower in the 18 to 44-year age group (25% vs. 38%), and higher in the 45 to 64-year age group (49% vs. 39%) and the 65 and older age group (27% vs. 23%) (Reference Table 3A.3.2.2.1 PDF [80] CSV [81]).

Among the 10 AORC subgroups, more than 2 in 3 of the 6.5 million AORC-related OP visits (69%) were associated with joint pain/effusion/other unspecified joint disorders and osteoarthritis; soft tissue disorders and rheumatoid arthritis accounted for about 12% each. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.2.2 PDF [82] CSV [83])

AORC-related OP visits for specific types of AORC differed by demographic variables. Women comprised 69% of all AORC-associated OP visits; their proportion was much higher for rheumatoid arthritis (83%) and diffuse connective tissue disease (88%). Men comprised 31% of all AORC-associated OP visits; their proportion was much higher for gout (81%) and osteoarthritis (67%) (Reference Table 3A.3.2.2.1 PDF [80] CSV [81]).

Persons aged 18 to 44 comprised 25% of all AORC-associated OP visits; their proportion was higher for diffuse connective tissue disease (38%) and carpal tunnel syndrome (38%). Those aged 45 to 64 comprised 49% of all AORC-associated OP visits; their proportion was higher for rheumatoid arthritis (63%). Those aged 65 and older comprised 27% of all AORC-associated OP visits; their proportion was much higher for osteoarthritis (40%) (Reference Table 3A.3.2.2.2 PDF [82] CSV [83]).

Non-Hispanic whites comprised 58% of all AORC-associated OP visits; their proportion was higher for spondylarthropathies (71%) and fibromyalgia (70%). Comparisons for other race/ethnic groups were difficult to determine. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.2.3 PDF [84] CSV [85])

There was little difference by geographic region. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.2.4 PDF [86] CSV [87])

Emergency department (ED) visits for AORC-related diagnoses, totaling 11.7 million, accounted for 12% of all ambulatory care visits in 2013 and 11% of all emergency department visits. An AORC-related condition was listed as the presenting (first) diagnosis for 2.8% of all ED care visits. (Reference Table 3A.3.0.1 PDF [9] CSV [10])

2013 AORC-related ED visits resembled those for all 2013 ED visits by sex and geographic area; they differed in age, being lower in the 18 to 44-year age group (29% vs. 49%) and higher in the 45 to 64-year age group (34% vs. 29%) and the 65 and older age group (37% vs. 23%). (Reference Table 3A.3.2.3.2 PDF [88] CSV [89])

Among the 10 AORC subgroups, 3 in 5 of the 11.7 million AORC-related ED visits were associated with joint pain/effusion/other unspecified joint disorders and osteoarthritis; soft tissue disorders and fibromyalgia accounted for 13% and 12%, respectively. (Reference Table 3A.3.0.1 PDF [9] CSV [10])

AORC-related ED visits for specific types of AORC differed by demographic variables. Women comprised 61% of all AORC-associated ED visits; their proportion was much higher for rheumatoid arthritis (77%), fibromyalgia (79%) and diffuse connective tissue disease (90%). Men comprised 39% of all AORC-associated ED visits; their proportion was much higher for gout (69%). (Reference Table 3A.3.2.3.1 PDF [90] CSV [91])

Persons aged 18 to 44 comprised 29% of all AORC-associated ED visits; their proportion was higher for diffuse connective tissue disease (40%), fibromyalgia (43%), and carpal tunnel syndrome (51%). Those aged 45 to 64 comprised 34% of all AORC-associated ED visits; this proportion was similar for most specific types of AORC. Those aged 65 and older comprised 37% of all AORC-associated ED visits; their proportion was much higher for osteoarthritis (66%), rheumatoid arthritis (49%), gout (56%), spondylarthropathies (50%), and other specified rheumatic conditions (49%). (Reference Table 3A.3.2.3.2 PDF [88] CSV [89])

Race/ethnicity was not a defined variable in the NEDS database. There was little difference by geographic region. (Reference Table 3A.3.2.3.4 PDF [92] CSV [93])

Disease burden can be measured in many ways. This is particularly important for AORC, which has a modest effect on conveniently measured outcomes like mortality, but a much larger impact on less conveniently measured outcomes important to functionality for most people. Such outcomes include effects on work, health-related quality of life, independence, and ability to keep doing valued life activities. Three of these burdens, along with adverse life style factors that are associated with arthritis, are addressed in the estimates below.

Bed Days and Lost Work Days

Bed days are defined as spending one-half or more days in bed due to injury or illness, excluding hospitalization. Data are averaged over three years for the NHIS to achieve larger, more powerful sample sizes. For the years 2013-2015, the proportion who had bed days among adults with arthritis was higher than that for adults with any medical condition (45% vs. 41%). The 24.6 million adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis and any bed days, 10% of the adult population, had an annual average of nearly 25 days spent in bed in the previous 12 months. This is far higher than the annual average of 14.5 bed days for the 41% of adults with bed days for any medical condition. Multiplying the 24.6 million adults by the mean bed days for arthritis resulted in 607 million bed days overall, or 55% of the 1.1 trillion bed days among adults reporting any medical condition. (Reference Table 3A.4.1.1 PDF [94] CSV [95])

Among adults with arthritis, females had a higher proportion than males of bed days (48% vs 41%) and a slightly higher mean number of days (25.6 vs. 23.1 days). Females with arthritis accounted for 65% of total bed days in 2013-2015. (Reference Table 3A.4.1.1 PDF [94] CSV [95])

Bed days are reported by a higher proportion of younger than by older adults with arthritis. Adults with arthritis had a higher proportion with bed days than adults reporting any medical condition in each age group: persons aged 18 to 44 years (59% vs. 46%), aged 45 to 64 years (50% vs. 41%), and aged 65 and older (35% vs. 31%). This was also true for the average number of bed days: 18 to 44 years (20.1 vs 9.3 days), 45 to 64 years (26.4 vs. 17.3 days), and 65 and older years (24.7 vs. 22.0 days). (Reference Table 3A.4.1.2 PDF [96] CSV [97])

Among racial/ethnic groups, those with arthritis had similar proportions reporting bed days (range 43%-47%) and a similar average number of bed days (range 21.4-25.6). (Reference Table 3A.4.1.3 PDF [98] CSV [99])

In the different geographic regions, those with arthritis had similar proportions with bed days (range 43%-47%) and a similar average number of bed days (range 22.4-27.2). (Reference Table 3A.4.1.4 PDF [100] CSV [101])

Persons in the workforce are defined as adults having worked at a job in the past 12 months. In the 2013-2015 NHIS sample, 81% of those age 18 to 44 held a job (56% of workforce), 74% of persons aged 45 to 64 years held a job (38% of workforce), and 20% of persons aged 65 and older were still working, comprising just under 6% of the workforce. Among the persons aged 65 and older, 83% were age 74 and younger. By sex, 73% of males reported being in the workforce, while 62% of females worked in the past 12 months. Males represented 52% of the workforce.

Lost work days for persons in the workforce are defined as absence from work due to illness or injury in the past 12 months, excluding maternity or family leave. For the years 2013-2015, the proportion of persons who had lost work days among adults with arthritis was lower than that for adults with any medical condition (23% vs. 30%). Among adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis, 12.6 million in the workforce reported an average of 14.3 work days lost in the past 12 months, nearly 5 days more than the 9.4 work days reported by adults with any medical condition. This resulted in 180.9 million total lost work days among adults with arthritis who are in the workforce, or 34% of the 533.2 million work days lost among adults reporting any medical condition.

Among adults with arthritis, females and males in the workforce had similar proportions with lost work days (23%-24%) and similar mean number of lost work days (14.2-14.4). Females accounted for 57% of total arthritis-attributed lost work days per year in 2013-2013 due to the higher number of females with arthritis. (Reference Table 3A.4.1.1 PDF [94] CSV [95])

Compared with older adults, younger adults with arthritis or any medical condition had a higher proportion of lost workdays. Adults with arthritis had a higher proportion of lost work days than adults reporting any medical condition for persons aged 18 to 44 years (47% vs. 42%), but proportions were similar for the older age groups. Although, overall, the proportion of persons with DDA reporting lost work days was slightly less than was reported for any medical condition, the average number of lost work days was higher among adults with arthritis than adults with any medical condition: 18 to 44 years (13.4 vs 8.2 days), 45 to 64 years (14.6 vs. 10.8 days), and 65 and older (15.3 vs. 12.6 days). Adults aged 45 to 64 accounted for 62% of total arthritis-related lost work days even though they only comprised 38% of the workforce and 47% of those with any medical cause. (Reference Table 3A.4.1.2 PDF [96] CSV [97])

Activity Limitations

Activity limitations are included in the National Health Interview Survey in both the family database and the adult database, with slightly different response codes. Respondents are asked first if they need help performing a variety of activities of daily living (ADL), such as personal care, bathing, eating, getting in/out of chair, and walking. They are also asked if they are “limited in the kind or amount of work” they can perform. If a limitation of any type has a “yes” response, respondents are shown a list of 34 possible medical conditions and asked to identify those that cause the limitation. Multiple causes may be identified. This section uses the adult database and focuses on cases where arthritis is identified as a cause of limitations. The variable AAAL, defined in the introduction to this arthritis section, is based on a single question in the NHIS1 and produces somewhat different numbers than this more inclusive definition of activity limitations.

Limitations in any activities of daily living (ADLs) include seven components. Musculoskeletal-related ADLs include only the three limitations related to movement and action commonly associated with musculoskeletal diseases and are 1) “needing help with routine needs,” 2) ”needing help with personal care,” and 3) “having difficulty walking without equipment.” Other ADLs are related to memory, vision, hearing, and other limitations.

Of the 35.6 million adults with limitations in any ADL, 23% (8.0 million) named arthritis as a cause; the proportion jumped to 29% for those with a limitation in musculoskeletal-related ADLs. One-third (33%, 4.5 million of 13.9 million) of adults with difficulty walking identified arthritis as a cause. More than 1 in 4 attributed their need for help with routine needs (2.8 million) or personal care (1.5 million) to arthritis. (Reference Table 3A.4.2.1 PDF [106] CSV [107])

These numbers demonstrate the large impact of arthritis on adults with limitations in any ADL or in musculoskeletal related ADLs. The effect was much stronger among females than males (Reference Table 3A.4.2.1 PDF [106] CSV [107]) and among older adults. (Reference Table 3A.4.2.2 PDF [108] CSV [109])

Little difference was found between adults by race/ethnicity except for slightly higher proportion of non-Hispanic blacks attributing limitations to arthritis. (Reference Table 3A.4.2.3 PDF [110] CSV [111]). Geographic region in the US does not seem to be a factor. (Reference Table 3A.4.2.4 PDF [112] CSV [113])

Work limitations are defined here as those unable to work now due to health or limited in kind or amount of work (i.e., “unable to work” or “limited in work”). Of the 28.1 million adults with work limitations per year in 2013-2015, arthritis attributable work limitations (AAWL) affected on average 23% (6.4 million). Among those with any medical condition limiting work, 23% attributed their inability to work now to arthritis, while 22% limited in kind or amount of work did so. Higher percentages of females and older workers identified arthritis as a cause for work limitations. There was little difference seen by race/ethnicity or geographical region. (Reference Table 3A.4.2.1 PDF [106] CSV [107]; Table 3A.4.2.2 PDF [108] CSV [109]; Table 3A.4.2.3 PDF [110] CSV [111]; and Table 3A.4.2.4 PDF [112] CSV [113]).

Quality of Life and Lifestyle Factors

Among persons with DDA, compared with those without DDA, Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) is worse on several scales. When assessed by self-reported health status, 27% of those with DDA reported fair/poor health compared to 12% of those without DDA. The DDA group also reported a higher mean number of days in the past month with poor physical health (6.6 vs 2.5 days), poor mental health (5.4 vs 2.8 days), or days with limitations in usual activities (4.3 vs 1.4 days).2 Using the same “unhealthy days” measures, an analysis of 2014 Humana Medicare Advantage members found that those with arthritis had more total unhealthy days, by 2.2 days per year, than those without arthritis, and that comorbid arthritis associated with hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and congestive heart failure resulted in significant increases in both physically and mentally unhealthy days.3

The prevalence of DDA and of AAAL is much higher among those with the adverse lifestyle factors of obesity, insufficient or no physical activity, and fair/poor self-rated health.4 (Reference Table 3A.4.3 PDF [118] CSV [119])

The Economic Cost [124] section of this report uses the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS), a standard source for cost of illness estimates, to estimate the total direct and indirect costs of musculoskeletal conditions and selected categories of musculoskeletal conditions, as well as the incremental direct and indirect costs specifically attributable to the selected category. Total costs are all costs for a patient regardless of the condition responsible; incremental costs are those costs attributed to a specified condition. A quick review of all economic terms used can be found by clicking HERE [125].

There are several important points to remember here. First, for arthritis and other rheumatic conditions, MEPS requires the use of selected 3-digit ICD-9-CM codes, using the 3- and 4-digit NADW AORC ICD-9-CM codes [126] to create a similar category called “arthritis and joint pain.” This approach has been used for a number of years and provides a comparative estimate of the costs of AORC. Additionally, costs estimates are per person and reported as mean per person costs. To arrive at the estimated aggregate cost, the mean per person cost is multiplied by the number of people affected, resulting in a total cost for conditions in the United States.

MEPS provides estimates of actual medical “expenditures,” meaning money changing hands, rather than medical “charges,” which are based on what is originally billed but rarely paid in full. Thus, the term direct costs, as used here, reflects actual medical expenditures. Indirect costs are those associated with lost wages. Aggregate costs for both direct and indirect costs are the sum of per-person costs across all individuals with the condition.

All-cause costs include medical expenditures or lost wages for persons with musculoskeletal disease, regardless of whether those costs are due to the musculoskeletal disease or another medical condition. Incremental costs are those estimated as attributable to musculoskeletal disease.

Direct Costs

Annual all-cause direct costs, in 2014 dollars, for arthritis and joint pain increased from a per person mean of $6,642 in the years 1996-1998 to $9,554 in 2012-2014. Incremental direct costs for arthritis and joint pain increased from a per person mean of $679 in the years 1996-1998 to a mean of $1,352 in 2012-2014, in 2014 dollars. The change in total mean costs was 44%, while incremental mean costs doubled. Incremental arthritis and joint pain costs showed a decline in 2012-2014 annual average costs compared to the previous five periods. (Reference Table 8.4.3 PDF [127] CSV [128]; Table 8.5.3 PDF [129] CSV [130])

Mean per person direct costs include ambulatory care, inpatient care, prescriptions, and other healthcare costs. In 2012-2014, ambulatory care accounted for about a third of per person direct costs, with inpatient care and prescriptions each accounting for approximately one-quarter (28% and 25%, respectively) of total cost. Over the past 18 years, prescription costs have seen the greatest change, rising nearly 140% per person in that time. Both inpatient and other healthcare costs remained steady at 9% and 11% increase, respectively. Ambulatory care increased by 59% over the same time period. (Reference Table 8.4.3 PDF [127] CSV [128])

Annual all-cause aggregate medical costs for persons with a diagnosis of arthritis and joint pain in the US increased from $192.4 billion in 1996-1998 to $626.8 billion, in 2014 dollars, for the years 2012-2014. Aggregate annual direct costs specifically attributed to arthritis and joint pain (incremental costs) in the US increased from $19.7 billion in 1996-1998 to $88.7 billion for the years 2012-2014, in 2014 dollars. While the increase over the 18-year period for total aggregate costs was more than 225%, the increase for incremental aggregate costs was greater than 350%, despite the recent decline in aggregate incremental costs. (Reference Table 8.6.3 PDF [135] CSV [136])

Annual per-person all-cause direct costs for arthritis and joint pain are highest for people age 65 and older, females, non-Hispanic whites, and residents of the Northeast region. Lower education and marital staus (divorced-widowed-separated) are also factors in higher cost. Public only insurance (Medicaid/Medicare) show the highest per person costs, in part because they serve a large share of the elderly population. (Reference Table 8.15.3 PDF [139] CSV [140])

Mean and aggregate total and incremental direct and indirect costs for osteoarthritis [141], rheumatoid arthritis [142], gout [143], and connective tissue disease [144], using the annual average for years 2008-2014 MEPS data, are calculated and shown in their respective sections.

Indirect Costs

“Indirect costs” as used in this report reflect estimates of earnings losses for persons with a work history who are unable to work due to a medical condition. They do not reflect supplemental measures, such as reduced productivity, worker replacement, or early retirement due to medical conditions.

Indirect costs are not estimated for the broad category of arthritis and joint pain.

Because many types of arthritis have a higher prevalence among older adults, we expect that the current aging of the population will increase the prevalence and impact of AORC unless new interventions are implemented within the near future. The projections of arthritis prevalence and AAAL take into account age and sex, but do not take into account potentially important factors such as the obesity epidemic and the increasing frequency of joint injuries.1 The age-adjusted percentage of AAAL among adults with arthritis increased 19% between 2002-2004 and 2013-2015.2 Previous costs of arthritis have been driven by age-related increases in prevalence,3 so future costs of arthritis are likely to be driven higher by the same age-related increase in prevalence, but also from the increasing frequency of surgical interventions.

Several data limitations exist for monitoring AORC burden in the future. First, on October 1, 2015, ICD-10-CM was required for use in clinical records; it was previously in use for death records. The current National Arthritis Data Workgroup definition of AORC uses ICD-9-CM codes. Due to significant changes in conceptualizing the new codes, a direct translation cannot be made. This means a new definition of AORC or some similar concept will be needed for analyses using ICD-based data in the future. CDC is working with ICD-10-CM translation experts and selected stakeholders to propose a draft standard ICD-10-CM based definition, which will be shared with the larger arthritis community to reach agreement on a new definition.

Second, there is a need for data on more specific conditions, for example rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and psoriatic arthritis, to help drive clinical (eg, treatment, quality of care) and public health (eg, self-management education, safe physical activity) efforts that allow for better incidence estimates in order to better understand risk. Electronic health records may prove helpful in creating valid measures. There is also a lack of data on patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) on pain and function in electronic health records and administrative databases. These outcome measures are important to assessing the impact/burden of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases.

Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions are not addressed with the same priority as many other chronic conditions, perhaps because such priorities are driven more by easily available measures of mortality rather than by more challenging measures such as quality of life, disability, and impact on work. However, there is a growing policy interest in the role of multiple chronic conditions in health and health costs,1 and AORC plays a major role from this perspective for at least three reasons. First, those with priority chronic conditions are highly affected by AORC, with about half of adults with heart disease or diabetes and about a third of adults with obesity affected by DDA.2,3,4 Second, arthritis is very common condition among individuals with two or more chronic conditions, regardless of the conditions considered.5 Third, those with arthritis as one of their multiple chronic conditions fare much worse on important life domains such as social participation restriction, serious psychological distress, and work limitations.6

There are widespread and consistent professional recommendations for most types of AORC that involve increasing self-management of the disease through education, physical activity, and achieving a healthy weight, but little progress is being made.1 Such behavioral interventions offer evidence-based improvements to patients without the side effects seen with medications and other interventions. While most clinical settings are not set up to help patients achieve these recommendations effectively, increasing clinical/community linkages may offer a better approach. To see if provider referrals to community resources is a better solution, approaches such as the 1.2.3 Approach to Provider Outreach [147] and Spread the Word: Marketing Self-Management Education Through Ambassador Outreach [148] are being pilot tested in communities.

The Healthy People [149] project started with the 1979 Surgeon General’s report, Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. The current version of Healthy People 2020 [150] has set nine arthritis objectives for the nation to achieve by 2020, but only limited progress has occurred with the current level of investments in interventions. Currently, four new developmental objectives are included in the Arthritis, Osteoporosis, and Chronic Back Conditions [151] topic area as part of a larger effort to insure that chronic pain, regardless of the original cause, is included in Healthy People 2020.

There is a need for more conveniently measured outcomes that are important to most people. Such outcomes include effects on work, activities, health-related quality of life, independence, and ability to keep doing valued life activities.

Research funding to develop and evaluate more effective clinical and public health interventions is relatively modest, given that arthritis is the most common cause of disability and is a large and growing problem, affecting 54.4 million adults now,2 and a projected 78 million by 2040.3 This is especially frustrating because even the evidence-based interventions we have now are not reaching the people who would benefit from them. Implementation research to translate effective interventions to clinical practice and/or community settings is needed.

Although most adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis are younger than age 65 and in their working years, the effect of their arthritis on employment and work, and the effect of reasonable workplace accommodations, have not been explored in depth. There is a need for the development and demonstration of web-based or app-based interventions for education, physical activity and achieving a healthy weight. This is an urgent issue right now and will continue to be an urgent issue as an aging workforce keeps working beyond age 65, as is anticipated.

As noted above, the use of ICD-9-CM codes for clinical and public health purposes ended with the healthcare system shift to the ICD-10-CM codes on October 1, 2015. This means the national surveys analyzed here that use ICD codes will shift to ICD-10CM as well. Standard definitions of generic and specific types of AORC need to be developed for clinical and public health researchers using the new ICD-10-CM codes; otherwise, investments in research will not be comparable and will be unable to build on each other.

Codes used in this analysis of AORC are based on the "National Arthritis Data Workgroup ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes for arthritis and other rheumatic conditions." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Arthritis Program, National Arthritis Data Workgroup.1

Osteoarthritis and allied disorders

715-Osteoarthritis and allied disorders

Rheumatoid arthritis

714-Rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory polyarthropathies

Gout and other crystal arthropathies

274-Gout

712-Crystal arthropathies

Joint pain, effusion and other unspecified joint disorders

716.1, .3-.6-.9-Other unspecified arthropathies

719.0, .4-.9-Other and unspecified joint disorders

Spondylarthropathies

720-AS/inflammatory spondylopathies

721-Spondylosis and allied disorders

99.3-Reiter’s Disease

696.0-Psoriatic arthopathy

Fibromyalgia

729.1-Myalgia and myositis unspecified

Diffuse connective tissue disease

710-Diffuse connective tissue disease [excl 710.0-.2]

710.2-Sicca syndrome (also called Sjögren's syndrome)

710.1-Systemic sclerosis (SSC, scleroderma)

710.0-Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Carpal tunnel syndrome

354.0-Carpal tunnel syndrome

Soft tissue disorders (excluding back)

726-Peripheral enthesopathies and allied disorders

727-Other disorders of synovium/tendon/bursa

728.0-.3, .6–.9-Disorders of muscle/ligament/fascia

729.0-Rheumatism, unspecified and fibrositis

729.4-Fascitis, unspecified

Other specified rheumatic conditions

95.6-Syphilis of muscle

95.7-Syphilis of synovium/tendon/bursa

98.5-Gonococcal infection of joint

136.1-Behcet’s syndrome

277.2-Other disorders purine/pyrimidine metabolism

287.0-Allergic purpura

344.6-Cauda equina syndrome

353.0-Brachial plexus/thoracic outlet lesions

355.5-Tarsal tunnel syndrome

357.1-Polyneuropathy in collagen vascular disease

390-Rheumatic fever w/o heart disease

391-Rheumatic fever w/heart disease

437.4-Cerebral arteritis

443.0-Raynaud’s syndrome

446-Polyarteritis nodosa and allied conditions [excl 446.5]

447.6-Arteritis, unspecified

711-Arthritis associated with infections

713-Arthropathy associated w/disorders classified elsewhere

716.0, .2, .8-Specified arthropathies

719.2, .3-Specified joint disorders

725-Polymyalgia rheumatica

Links:

[1] http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/data_statistics/case_definition.htm

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.1.1.pdf

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.1.1.csv

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a201png

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.2.0.1.png

[6] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib60/juvenile-arthritis

[7] http://www.fmaware.org/about-fibromyalgia/prevalence

[8] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiia90/icd-9-cm-codes-aorc

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.1.pdf

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.1.csv

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a301png

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.3.0.1.png

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.2.pdf

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.2.csv

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.3.pdf

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.3.csv

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.4.pdf

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.4.csv

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.5.pdf

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.0.5.csv

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.1.pdf

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.1.csv

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.2.pdf

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.2.csv

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.3.pdf

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.3.csv

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.4.pdf

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.0.4.csv

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a3101png

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.3.1.0.1.png

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a3102png

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.3.1.0.2.png

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.1.1.pdf

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.1.1.csv

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.1.2.pdf

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.1.2.csv

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.1.3.pdf

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.1.3.csv

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.1.4.pdf

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.1.4.csv

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a3111png

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.3.1.1.1.png

[43] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiia50/economic-burden-aorc

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a3121png

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.3.1.2.1.png

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.3.1.pdf

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.3.1.csv

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.3.2.pdf

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.3.2.csv

[50] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.3.3.pdf

[51] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.3.3.csv

[52] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.3.4.pdf

[53] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.1.3.4.csv

[54] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a3131png

[55] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.3.1.3.1.png

[56] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.1.pdf

[57] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.1.csv

[58] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.2.pdf

[59] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.2.csv

[60] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.3.pdf

[61] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.3.csv

[62] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.4.pdf

[63] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.0.4.csv

[64] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a3201png

[65] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.3.2.0.1.png

[66] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a3202png

[67] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.3.2.0.2.png

[68] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a3203png

[69] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.3.2.0.3.png

[70] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a3204png

[71] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.3.2.0.4.png

[72] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.1.1.pdf

[73] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.1.1.csv

[74] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.1.2.pdf

[75] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.1.2.csv

[76] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.1.3.pdf

[77] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.1.3.csv

[78] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.1.4.pdf

[79] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.1.4.csv

[80] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.2.1.pdf

[81] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.2.1.csv

[82] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.2.2.pdf

[83] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.2.2.csv

[84] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.2.3.pdf

[85] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.2.3.csv

[86] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.2.4.pdf

[87] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.2.4.csv

[88] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.3.2.pdf

[89] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.3.2.csv

[90] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.3.1.pdf

[91] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.3.1.csv

[92] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.3.4.pdf

[93] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.3.2.3.4.csv

[94] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.1.1.pdf

[95] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.1.1.csv

[96] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.1.2.pdf

[97] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.1.2.csv

[98] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.1.3.pdf

[99] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.1.3.csv

[100] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.1.4.pdf

[101] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.1.4.csv

[102] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a411png

[103] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.4.1.1.png

[104] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a412png

[105] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.4.1.2.png

[106] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.2.1.pdf

[107] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.2.1.csv

[108] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.2.2.pdf

[109] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.2.2.csv

[110] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.2.3.pdf

[111] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.2.3.csv

[112] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.2.4.pdf

[113] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t3a.4.2.4.csv

[114] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a421png

[115] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.4.2.1.png

[116] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a422png

[117] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.4.2.2.png

[118] http://bmus_e4_t3a.4.3.pdf

[119] http://bmus_e4_t3a.4.3.csv

[120] https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_questionnaires.htm

[121] https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd14.160495.

[122] https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2017/16_0495.htm

[123] http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6609e1

[124] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/viii0/economic-cost

[125] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/viiia0/definitions

[126] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiia80/icd-9-cm-codes-aorc

[127] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.3.pdf

[128] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.3.csv

[129] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.3.pdf

[130] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.3.csv

[131] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a701png

[132] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.7.0.1.png

[133] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a702png

[134] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.7.0.2.png

[135] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.3.pdf

[136] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.3.csv

[137] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g3a703png

[138] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g3a.7.0.3.png

[139] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.15.3.pdf

[140] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.15.3.csv

[141] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib10/osteoarthritis

[142] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib21/rheumatoid-arthritis

[143] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib30/gout-0

[144] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib23/connective-tissue-disorders

[145] http://www.hhs.gov/ash/initiatives/mcc/

[146] http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.120203

[147] http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/interventions/marketing-support/1-2-3-approach/index.html

[148] https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/marketing-support/ambassador-outreach/docs/pdf/ambassador-guide.pdf

[149] http://www.healthypeople.gov/

[150] https://www.healthypeople.gov/

[151] http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/proposed-objective-landing-page/arthritis-osteoporosis-and-chronic-back-conditions

[152] http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search/Search-the-DData?&f[0]=field_topic_area%3A3507

[153] http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/data_statistics/arthritis_codes_2004.pdf