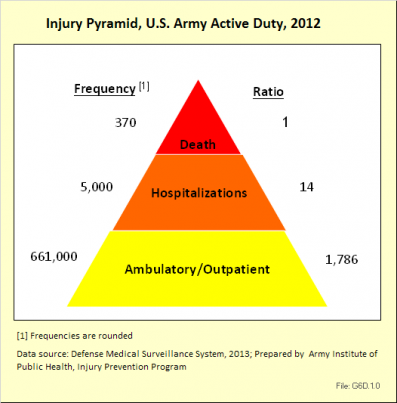

In 2012, there were approximately 370 injury-related deaths, 5,000 injury-related hospitalizations (3,000 acute injuries and 2,000 injury-related musculoskeletal conditions), and 661,000 injury-related outpatient visits (245,000 acute injuries and 415,000 injury-related musculoskeletal conditions).

Fatalities have been a major focus of injury prevention activities in the past. As illustrated by these data, however, there are far more injury-related hospitalizations and outpatient visits than deaths. These nonfatal outcomes result in significant losses in duty time and manpower for the Army.

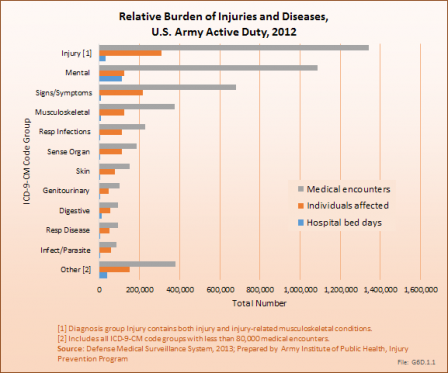

In 2012, injuries accounted for approximately 30% of all medical encounters. Injuries were the leading cause of medical encounters and affected more individuals than all other medical conditions, including mental health disorders.

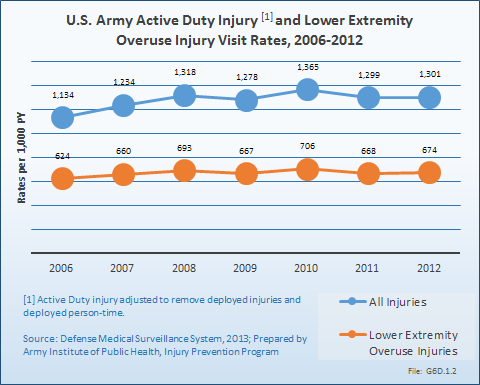

Rates of all injury visits among nondeployed active duty soldiers climbed slightly between 2006 and 2012. During this period, more than half the injury visits were due to lower extremity overuse injuries.

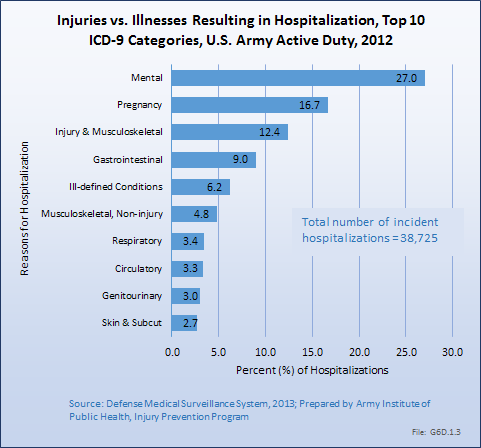

In 2012, out of approximately 39,000 incident hospitalizations, three major diagnoses groups accounted for over half of all admissions (56%). The top three reasons for hospitalization were mental disorders (27%), pregnancy-related issues (17%), and injuries and injury-related musculoskeletal conditions (12%).

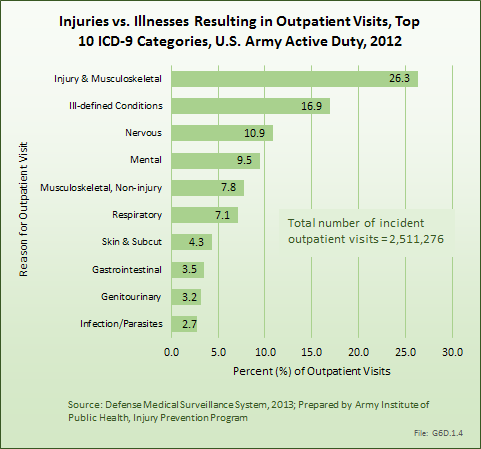

A total of 2,511,276 unique outpatient visits were made by active duty Army personnel. Injuries and injury-related musculoskeletal conditions were responsible for 26%, or more than 660,000, of visits.

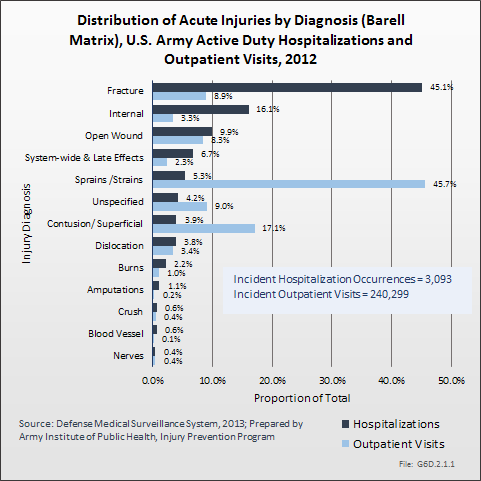

Acute injuries among active duty, nondeployed US Army soldiers are characterized by the types of injuries incurred, as well as the bodily site of the injuries. Two types of analytical injury matrices are available to further describe acute injuries and injury-related musculoskeletal conditions: (1) the Barell Injury Diagnosis matrix1 and (2) the injury-related musculoskeletal conditions matrix.2 Matrices report ICD-9-CM code frequencies by type of injury and body region. (Reference Table 6D.1 PDF [1] CSV [2] and Table 6D.2 PDF [3] CSV [4])

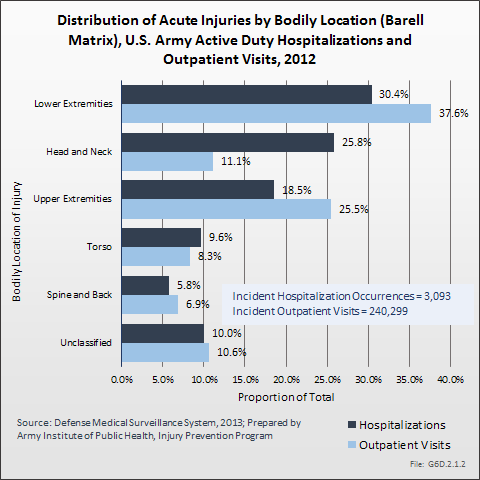

In 2012, there were 3,093 acute traumatic injuries (coded in the 800–900 ICD-9-CM code series) requiring hospitalization. Leading specific reasons for hospitalizations included fractures of the lower leg and/or ankle (13 %), facial fracture (6%), and fracture of the foot/toes (3%). Comparing all body regions, the lower extremity accounted for 30%, the upper extremity for 19%, and the head for 16%. Within the head region, traumatic brain injury, including skull fracture, accounted for 15%, and other specified head injuries accounted for less than 1%. (Reference Table 6D.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

During the same year, US Army active duty, nondeployed soldiers incurred 240,299 acute traumatic injuries (coded in the 800–900 ICD-9-CM code series) for which outpatient care was required. Leading specific reasons for outpatient visits included strains/sprains to the lower leg and/or ankle (9%) and strains/sprains of the shoulder/upper arm (7%). Body regions most affected were lower extremities (38%), upper extremities (26%), and the head and neck region (TBI and other head, face, and neck) (11%). (Reference Table 6D.2 PDF [3] CSV [4])

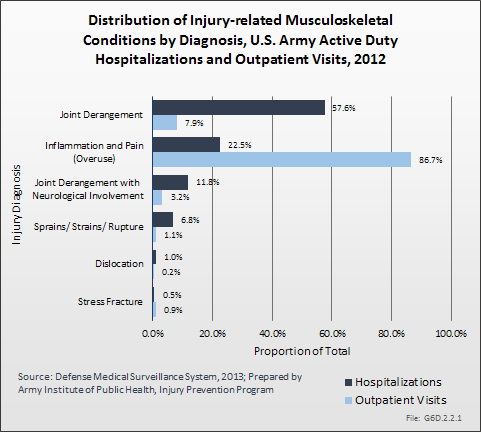

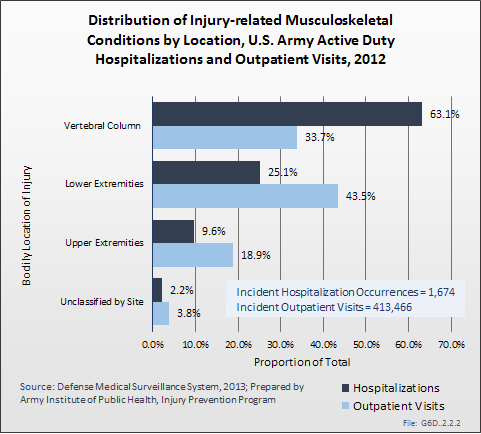

In 2012, there were 1,674 hospitalizations due to injury-related musculoskeletal conditions, roughly one-half the number of acute traumatic injuries requiring hospitalization. The most common types of injury-related musculoskeletal conditions leading to hospital admission were joint derangement (58%), followed by inflammation and pain due to overuse (23%). Joint derangement with neurological involvement accounted for another 12%. The vertebral column (including spine/back) was the most affected by injury-related musculoskeletal conditions (63%), followed by lower extremities (25%) and upper extremities (10%). (Reference Table 6D.3 PDF [5] CSV [6])

There was nearly twice the number of injury-related musculoskeletal conditions requiring outpatient visits as there were acute traumatic injuries. In 2012, there were a total of 413,466 outpatient visits for injury-related musculoskeletal conditions (710–739 ICD-9-CM series). Most outpatient visits for injury-related musculoskeletal conditions involved inflammation and pain due to overuse (87%). Lower extremities (44%) was the body region most often treated on an outpatient basis, followed by the vertebral column (including spine/back) at (34%), and upper extremities at 19%. The leading specific injury-related musculoskeletal conditions requiring outpatient treatment were inflammation and pain (overuse) to the knee and/or lower leg (20%), inflammation and pain (overuse) to the lumbar spine (18%), inflammation and pain (overuse) to the ankle and/or foot (14%), and inflammation and pain (overuse) to the shoulder (12%). (Reference Table 6D.4 PDF [7] CSV [8])

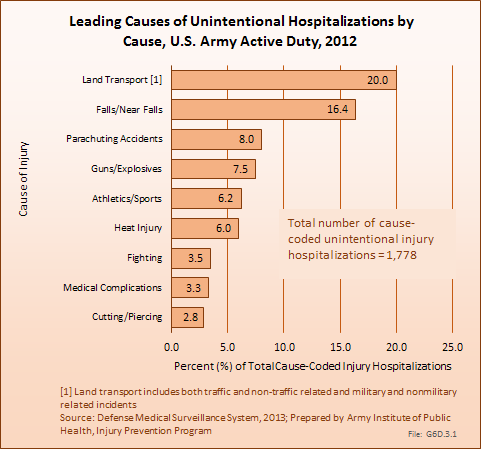

The leading cause of unintentional injury hospitalizations in 2012 was land transport accidents (20%), followed by falls or near-falls (16%). Parachuting and guns/explosives accounted for 8% each. A total of 6% of unintentional injury hospitalizations were due to sports and another 6% were due to heat injury. The top nine causes of unintentional injuries accounted for nearly three-fourths of hospitalizations (74%). Intervention strategies to address many of these issues are available.

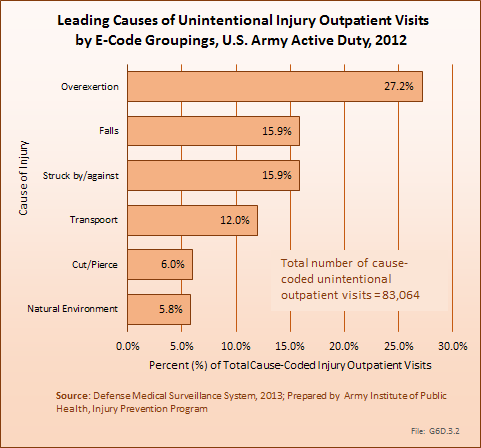

The leading causes of unintentional injury outpatient visits in 2012 were attributed to overexertion (27%), falls (16%), and injuries due to soldiers being struck by or against objects or other people (16%).

To address a large and complex problem such as injuries in the US Army, a systematic approach is needed.1 This approach should include routine assessment of surveillance data, data-driven and objective priorities, pursuit of detailed risk factor analyses, evaluation of existing prevention strategies, and research to address gaps in intervention and risk factor knowledge. Over the past three decades, contributions to Army injury prevention have been made in each of these areas, including the establishment of deployment injury surveillance capabilities2 and implementation of a data-driven process to define Army injury prevention priorities.3 Epidemiologic analyses and program evaluations have described potential technologies to address motor vehicle crashes among Army personnel4 and the effects of extreme conditioning program elements incorporated into unit physical training.5 Systematic reviews have defined physical training programs to enhance load carriage performance6 and interventions to prevent physical training-related injuries.7 Research efforts have quantified physical-training activities in Army basic training8 and described physical training to improve performance on tactical occupational tasks.9

To maintain progress, continued focus on leading causes of Army injuries such as physical training/exercise, sports, falls, and motor vehicle (land transport) crashes is needed. Collaborations with academia and other government organizations will aid in identifying modifiable causes, risk factors, and effective prevention strategies. Fostering existing and new partnerships between Army leadership, public health, safety, research, health promotion, and other communities will be critical for the success of military injury prevention activities. Given the magnitude and severity of the problem of injuries, effective injury prevention will make a significant contribution to the health and productivity of soldiers and the Army.

The material presented here is adapted from the following sources:

Esther Dada-Laseinde, Michelle Canham-Chervak, Bruce H. Jones: U.S. Army Annual Injury Epidemiology Report 2008. USAPHC (PROV) REPORT NO. 12-HF-0APLa-09. U.S. Army Public Health Command (Provisional), 5158 Blackhawk Rd, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland 21010-5403.

Esther Dada, Michelle Canham-Chervak, Bruce H. Jones: U.S. Army Injury Surveillance Summary 2012. U.S. Army Institute of Public Health, Epidemiology and Disease Surveillance Portfolio, Injury Prevention Program.

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6D.1.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6D.1.csv

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6D.2.pdf

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6D.2.csv

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6D.3.pdf

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6D.3.csv

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6D.4.pdf

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6D.4.csv