[13]

[13]

Soft tissue tumors, like bone tumors, are called sarcomas, and are encountered more frequently than bone and joints tumors. Soft tissue tumors originate in connective or non-glandular tissue and can develop in any part of the body that contains fat, muscle, nerve, blood vessels, fibrous tissues, and in any deep tissues, including tissues surrounding joints, bones, or deep subcutaneous tissues. More than half of soft tissue sarcomas develop in the arms or legs. About one in five (20%) are found in the abdominal cavity and present with symptoms similar to other abdominal-based health problems. The rest begin in the head and neck area or in and on the chest or abdomen (about 10% each).1 The differentiating feature of soft tissue tumors (sarcomas) is that they arise from the connective tissues rather than from gland forming organs such as kidneys, lungs, intestines, breasts, prostate, or thyroid glands.

There also are a vast number of non-malignant soft tissue neoplasms and tumors such as lipomas. In addition, typically included are cystic lesions of the deep tissues. Additional information on soft tissue sarcomas can be found in multiple sources such as Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors.2

The reader is referred to the data tables 6A.B.2.1 thru 6A.B.2.7 for a more robust appreciation of these tumors. These tables show the latest NCDB demographic and survivorship analyses of soft tissue cancers, providing additional understanding of the demographics, anatomic distribution, nature, treatment and prognosis of these sarcomas and their treatments and results.

There are multiple soft tissue sarcomas with varying degrees of aggressive behavior, but virtually all have the capacity to metastasize and cause death. Treatment for high-grade soft tissue sarcomas is typically resection (removal) and radiation. Chemotherapy is playing an ever-increasing role, especially in high-grade (fast-growing) and metastatic cases.

Cancer cells are often referred to as differentiated versus undifferentiated. Differentiation describes how much or how little the tumor tissue microscopically resembles the normal tissue from which it originated. Well-differentiated cancer cells look much like normal cells and tend to grow and spread more slowly than poorly differentiated or undifferentiated cancer cells. Differentiation is used in tumor grading systems, which are different for each type of cancer.1 The most common types of soft tissue sarcomas are described below.2

Malignant Fibrous Histiocvtomas (MFH)/Pleomorphic Sarcomas (PS) Not Otherwise Specified (NOS)

The most commonly encountered soft tissue sarcoma is malignant fibrous histiocytoma, a tumor of the fibrous tissue most often occurring in the arms or legs. The least differentiated of the sarcomas, in many cases it represents a poorly defined, high-grade soft tissue sarcoma that cannot be further defined pathologically (histologically). A recent trend is to classify these poorly differentiated sarcomas as pleomorphic sarcomas or spindle cell sarcomas not otherwise specified (NOS), rather than the previous designation as malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Poorly differentiated sarcomas typically affect older individuals. Analysis of annual rates of MFH and PS reflect this evolving diagnostic trend.

Liposarcomas

The next most commonly encountered and reported soft tissue sarcoma is liposarcoma, a malignant tumor of the fatty (adipose) tissues. This sarcoma also is more common in older persons. There are several subtypes ranging from the low-grade lipoma-like liposarcoma that rarely metastasizes to high-grade pleomorphic liposarcomas and round cell liposarcomas, which have a prognosis similar to malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Liposarcomas can develop anywhere in the body, but they most often develop in the thigh, around the knee, and inside the back of the abdomen. Seen in a wide range of patient ages, liposarcomas occur most frequently in adults between 50 years and 65 years old. Some liposarcomas grow very slowly, whereas others can grow quickly.

Synovial Sarcomas

The third most commonly encountered soft tissue sarcoma is synovial sarcoma, which is more likely to affect younger adults than previously mentioned sarcomas. The most common location is the thigh. Despite the name synovial sarcoma, most do not occur in joints or in the synovium of joints. Synovial sarcomas tend to occur mostly in young adults but can also occur in children and in older people. Many of these cases respond very favorably to chemotherapy with significant shrinkage of the tumor, although resection (surgical removal) and radiation remain the cornerstones of current therapy. Prognosis is similar to malignant fibrous histiocytoma and the other high-grade soft tissue sarcomas mentioned above.

Tumors of Muscle Tissue

Leiomyosarcomas

Smooth muscle (involuntary muscle) cells are found in internal organs such as stomach, intestines, blood vessels, or uterus. This muscle tissue gives these organs the ability to contract involuntarily. Leiomyosarcomas are malignant tumors of involuntary muscle tissue. They can occur almost anywhere in the body, but most often are found in the uterus. A second common site is the retroperitoneum (back of the abdomen) and in the internal organs and blood vessels where leiomyomas (benign version of similar tumor) also arise. Less often, they develop in the deep soft tissues of the legs or arms. They tend to occur in adults, particularly the elderly. Since they often arise from the smooth muscle cells in the walls of arteries, resection of extremity leiomyosarcomas frequently requires a concomitant vascular reconstruction.

Rhabdomyosarcomas

Skeletal muscles are the voluntary muscles that control and allow movement of arms and legs and other body parts. Rhabdomyosarcomas are malignant tumors of skeletal muscle. These tumors commonly grow in the arms or legs, but they can also begin in the head and neck area and in reproductive and urinary organs, such as the vagina or bladder. Rhabdomyosarcomas are primarily tumors of children. Clinically and behaviorally, they are in a class by themselves. They are treated with aggressive chemotherapy, as well as surgery and/or radiation in many cases. The aggressive treatments often cause permanent life-altering disability, even in survivors. For more information, see the American Cancer Society document "Rhabdomyosarcoma [2].“

Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

Malignant schwannomas, neurofibrosarcomas, and neurogenic sarcomas are malignant tumors of the protective lining that surrounds nerves. The currently favored name for these sarcomas is malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. A rare form of cancer, it often has an association with neurofibromatosis and thus may possess a genetic component.

Tumors of Blood Vessels and Lymph Vessels

Angiosarcomas (Hemangiosarcomas)

Malignant tumors can develop either from blood vessels (hemangiosarcomas) or from lymph vessels (lymphangiosarcomas). These tumors often develop in a part of the body that has been exposed to radiation. Angiosarcomas are sometimes seen in the breast after radiation therapy for breast cancer or in the arm on the same side as a breast that has been irradiated or removed by mastectomy. They are difficult to cure as they spread through the bloodstream to other parts of the body and often spread extensively through the local tissues.

Hemangiopericytoma

These are tumors of perivascular tissue (tissue around blood vessels). They most often develop in the legs, pelvis, and retroperitoneum (the back of the abdominal cavity) and are most common in adults. These can be either benign or malignant. They do not often spread to distant sites, tending to recur where they started, even after surgery, unless widely excised. Following recent research and further histologic, genetic, and clinical evaluations, hemangiopericytomas have recently been reclassified as one end of the spectrum of malignant solitary fibrous tumors or possibly identical to malignant solitary fibrous tumors.

Hemangioendothelioma

This is a less aggressive blood vessel tumor than hemangiosarcoma, but still considered a low-grade cancer. It usually invades nearby tissues and sometimes metastasizes to distant parts of the body. It may develop in soft tissues or in internal organs, such as the liver or lungs.

Kaposi Sarcoma

These cancers are composed of cells similar to those lining blood or lymph vessels. In the past, Kaposi's sarcoma was an uncommon cancer mostly seen in older people with no apparent immune system problems. It is now most common in people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It also develops in organ transplant patients who are taking medication to suppress their immune system. It is probably related to infection with a virus called human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8).

Tumors of Fibrous Tissue

Fibrous tissue forms tendons and ligaments and covers bones, muscles, and joint capsules, as well as other organs in the body.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH)

MFH is found most often in the arms or legs. Less often, it can develop inside the back of the abdomen. This sarcoma is most common in older adults. Although it mostly tends to grow locally, it can spread to distant sites. It is the most commonly diagnosed soft tissue sarcoma, although now these are more often classified as pleomorphic sarcoma, not otherwise specified (NOS), as discussed in the introduction section of soft tissue cancers.

Fibrosarcoma

Fibrosarcomas are cancers of fibrous tissue. They have a characteristic herringbone cloth pattern when viewed under the microscope. Fibrosarcomas most commonly affect the legs, arms, or trunk. They are most common between the ages of 20 years and 60 years, but can occur at any age, even in infancy.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP)

These tumors are slow-growing cancers of the fibrous tissue beneath the skin, usually noted in the trunk or limbs. They invade nearby tissues but rarely metastasize. They primarily affect young adults. Due to their slow, insidious growth, their uncommon occurrence, and their innocuous appearance, diagnosis is often delayed. The local recurrence rate is higher than many sarcomas and has been reported to be as high as 50% in some studies. While death due to disease is uncommon (<5%), the local recurrences can cause significant local morbidity.

Fibromatosis/Desmoid tumors

Fibromatosis is one of the names given to neoplastic tumors with features between fibrosarcomas and benign tumors, such as fibromas and superficial fibrous diseases like Dupytren's disease. They tend to grow slowly, but steadily. These tumors are often referred to as desmoid tumors. Although they are benign and do not metastasize, they do form in response to genetic alterations similar to many cancers and can cause great disability and even death. These tumors can invade nearby tissues, causing great havoc and occasionally even death. Some doctors may consider these to be a type of low-grade fibrosarcomas; most, however, regard them as benign but locally aggressive tumors. Certain hormones, particularly estrogen, may increase the growth of some desmoid tumors. There has been a very recent evolution in the thinking about this disease, with an evolution toward a greater role for careful observation after diagnosis, with surgical intervention being less enthusiastically employed, reserving such for more painful and/or aggressively growing tumors. Antiestrogen drugs are sometimes useful in treating desmoids that cannot be completely removed by surgery. Radiation therapy plays a role in treatment, especially when the tumor cannot be resected or in recurrent cases. There are ongoing chemotherapeutic trials in place with newer agents that interrupt the various biological processes in the growth of these tumors that hold promise for future patients. Additional research into the biology and treatment of these, and virtually all tumors, is clearly indicated.

Tumors of Uncertain Tissue Type

Through microscopic examination and other laboratory tests, doctors can usually find similarities between most sarcomas and certain types of normal soft tissues, thus, allowing them to be classified based on this histologic appearance. However, some sarcomas have not been linked to a specific type of normal soft tissue due to their unique appearance that does not closely resemble any normal single tissue type.

Malignant mesenchymoma

These very uncommon sarcomas contain areas showing features of at least two types of sarcoma, including fibrosarcomatous tissue per the original description. Since all connective tissue derive from undifferentiated mesenchymal tissues in an embryologic sense, it has been termed Mesenchymoma. The term has fallen out of favor, and it is now thought that many cases may be better classified as one of the subtypes of sarcomas based on the tissue type contained within the tumor.3

Alveolar soft-part sarcoma

This rare cancer primarily affects young adults. The legs are the most common location of these tumors. One of the most vascular (many tumor-contained and tumor-associated blood vessels) of all sarcomas, it induces an extensive network of vessels to grow in and around the tumor. Because of their very slow growth rate, a delay in diagnosis can occur. Unfortunately, it ultimately has a high mortality rate and can lead to death years after diagnosis. The rate of progression can be quite slow; late metastases are common.

Epithelioid sarcoma

This sarcoma often develops in tissues under the skin of the hands, forearms, feet, or lower legs. Adolescents and young adults are often affected. These are often misdiagnosed as infections and chronic infectious ulcers because of their innocuous appearance and uncommon occurrence. This sarcoma has a much higher propensity for lymph node metastasis than most sarcomas, which usually preferentially metastasize to the lung.

Clear cell sarcoma

This rare cancer often develops in tissues of the arms or legs. It recently has been determined to be a variant of malignant melanoma, a type of cancer that develops from pigment-producing skin cells. How cancers with these features develop in parts of the body other than the skin is not known. As a melanoma, it behaves differently than sarcomas. It has a propensity to spread through the lymphatic system. Local recurrence is common; therefore, wide resections are required for complete local eradication.

Other Types of Sarcoma

There are other types of soft tissue sarcomas, but they are less commonly encountered and not included in this discussion.

A recently published study, based on the National Cancer Database NCDB of the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancers, reports the 13-year experience (1998-2010) with 34 of the most commonly encountered soft tissue sarcomas. This report provides a good overview of the US experience with soft tissue sarcomas, including survival curves, the 2- and 5-year survivorship rate, and various demographic data.4

Soft tissue sarcomas account for less than 1% of all cancer cases diagnosed each year, and for a similar proportion of cancer deaths in any given year.

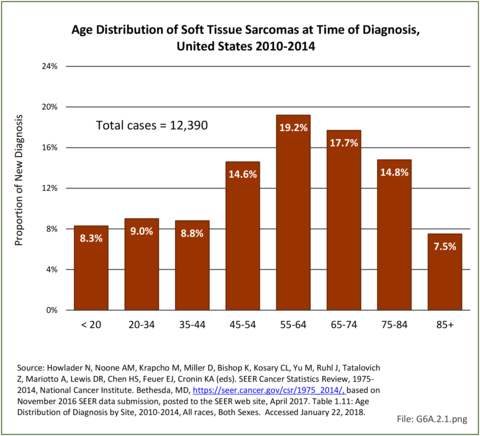

In terms of case numbers, the musculoskeletal health burden in the United States from soft tissue sarcomas is three to four times greater than that of bone and joint sarcomas. For the period from 2010 to 2014, the annual average number of soft tissue neoplasms, including the heart, approximated 15,500 cases/year in the SEER database. Estimated new cases for 2018 by the American Cancer Society are 13,040.1 Soft tissue sarcomas come in a wide variety of forms that affect different age groups, but the most frequently encountered soft tissue sarcomas affect adults age 45 and older. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [4] CSV [5])

As previously noted, the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB), a joint program of the Commission on Cancer and the American College of Surgeons, maintains the most thorough database on patients diagnosed with soft tissue sarcomas. Although the NCDB was not created to serve as an incidence based registry, it currently gathers data on approximately 72% of the cancers treated in the United States.2 It should be noted this percentage varies from year to year based on the participation and reporting by hospitals to this voluntary database.

A 2014 report by Corey, Swett, and Ward examined the adult cases reported to the NCDB of soft tissue sarcomas during a 13-year interval (1998-2010). In 2010, 5,070 soft tissue sarcomas were reported to the NCDB. While the numbers of soft tissue sarcomas reported to the NCDB increased by 19% over this 13-year period, the number of bone sarcomas reported to the NCDB increased by only 10.7% during this same time.3 However the NCDB is not an incidence or prevalence based database, and the number can simply reflect a change in makeup of the reporting member institutions.

Soft tissue sarcomas can be found among all ages, with the risk of developing soft tissue cancer very small, ranging from 0.33% at 20 years to 0.17% at 75 years of age. However, due to the smaller population count in older cohorts, the share of cases diagnosed after the age of 55 is larger than in younger cohorts. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [4] CSV [5], Table 6A.A.1.3.2 PDF [8] CSV [9], and Table 6A.A.1.6.2 PDF [10] CSV [11])

The rate at which males are diagnosed with soft tissue sarcomas has historically been higher than for females, with corresponding increases or decreases found in both sexes. The most recent rates from the NCI are for the year 2014 and are 4.1/100,000 for males and 2.9/100,000 for females. Males are diagnosed with soft tissue sarcomas at a slightly higher age than females. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.1.3 PDF [14] CSV [15] and Table 6A.A.1.7 PDF [16] CSV [17])

Blacks are diagnosed an average of eight years earlier than those who are white. In the 1970s and 1980s, the incidence rates for soft tissue sarcomas was slightly higher among the black population than for the white population. However, in the early 1990s a shift was observed and today incidence rates are higher among whites. In 2014, the rates were 3.5 and 3.3 per 100,000 persons, respectively, for whites and blacks. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.7 PDF [16] CSV [17] and Table 6A.A.1.1.4 PDF [18] CSV [19])

The 5-year survival rate in 2010-2014 for soft tissue sarcomas is reported at 64% by the SEER database and an overall relative survival rate of 50% by the American Cancer Society.1 This rate is similar to that for leukemia, colon and rectum, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma cancers. Average length of survival after diagnosis is 5 years, similar to that of breast, colon, and bladder cancers. White women have a slightly higher 5-year survival rate than do men and live an average of 1 year longer after diagnosis. Black women are diagnosed at about the same average age as black men with soft tissue sarcomas but live an average of two years longer after diagnosis. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.5.1 PDF [22] CSV [23]; Table 6A.A.1.7 PDF [16] CSV [17]; and Table 6A.A.1.8 PDF [24] CSV [25])

For high-grade soft tissue sarcomas, the most important prognostic factor is the stage at which the tumor is identified. Staging criteria for soft tissue sarcomas are primarily determined by whether the tumor has metastasized or spread elsewhere in the body. Size is highly correlated with risk of metastasis and survival. In general, the prognosis for a soft tissue sarcoma is poorer if the sarcoma is large. As a general rule, high-grade soft tissue sarcomas over 10 cm in diameter have an approximate 50% mortality rate and those over 15 cm in diameter have an approximate 75% mortality rate.

The staging criteria of soft tissue sarcoma of the National Cancer Institute groups sarcomas by whether they are still confined to the primary site (called localized); have spread to nearby lymph nodes or tissues (called regional); or have spread (metastasized) to sites away from the main tumor (called distant). The 5-year survival rates for soft tissue sarcomas have not changed much for many years. The corresponding 5-year relative survival rates were:

• 83% for localized sarcomas (56% of soft tissue sarcomas were localized when they were diagnosed)

• 54% for regional stage sarcomas; (19% were in this stage)

• 16% for sarcomas with distant spread (16% were in this stage)

The 10-year relative survival rate is only slightly worse for these stages, meaning that most people who survive 5 years are probably cured.1

Sarcomas are often staged by orthopedic oncologists with a staging system established by Dr. William Enneking and adopted and modified by surgical societies primarily consisting of orthopedic oncologists. That may have accounted for the lack of AJCC staging data in many cases of bone and soft tissue sarcomas reported to the NCDB. Nearly 40% of cases for 2000-2011 reported in the NCDB data have an unknown stage. This is a much higher proportion than found among other common cancer types, making it difficult to compare the severity of soft tissue sarcomas to other cancers.

From 2004-2015 inclusive, information on insurance coverage was available for roughly 65,015 patients treated with soft tissue sarcomas. The largest insurance payer was private insurance (51.0%), followed by Medicare and Medicaid (30.9% and 8.9%) respectively. Other government payors covered 1.4%, while 4.8% were uninsured and payor status was unknown in 3.0%. (Reference Table 6A.B.2.8 PDF [29] CSV [30])

The total economic costs of malignant soft tissue sarcoma are unknown. Surgery is often the first line of treatment for soft tissue sarcoma. Multiple therapies may be needed during the course of the patient's disease, especially in more advanced cases. In later stages of the disease in those not cured with surgery alone, significant costs will accumulate as patients typically develop pulmonary disease and ultimately die. Chemotherapy, and subsequently hormone therapy, immunotherapy, bone marrow transplant, and endocrine treatments are undertaken in a small number of cases that fail standard treatments. Overall, costs will vary with treatments utilized, number, and intensity of treatments, and can easily top $100,000 for a single patient that receives surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. (Reference Table 6A.B.2.6 PDF [33] CSV [34])

Throughout the years 2005--2008, one study reported that the average professional charge for a primary excision was $9,700 and $12,900 for re-excision. Although every 1-cm increase in size of the tumor results in an increase of $148 for a primary excision, size was not an independent factor affecting re-excision rates. The grade of the tumor was positively associated with professional charge, such that higher-grade tumors resulted in higher charges compared to lower-grade tumors. Analysis including professional, technical, and indirect charges revealed that, on average, patients undergoing definitive primary excision at their cancer treatment center were charged $40,230. This compared to $44,770 for patients receiving definitive re-excision of unsuccessful or incomplete previous resections at the same cancer treatment center. This higher cost did not include the charges and costs generated by their previous unsuccessful or incomplete previous attempt at resection.1

This analysis confirms that proper work-up, evaluation, and treatment are key to maintain costs, as well as improve the outcome for these patients. This cost analysis did not include the costs associated with chemotherapy or radiation therapy, or the costs of diagnostic and follow-up laboratory and radiographic studies, nor the actual costs of care.

The majority of sarcomas develop in people with no known risk factors, and there is currently no known way to prevent these cases. Whereas future developments in genomic research may allow genetic testing to identify persons with increased risk of developing soft tissue sarcomas, few such predictors are available at present. Reporting suspicious lumps and growths or unusual symptoms to a doctor, and appropriate evaluation of such abnormalities can help diagnose soft tissue cancer at an earlier stage. Treatment is thought to be more effective when detected early, as smaller-diameter sarcomas have been shown to have improved outcome compared to large sarcomas.

Whenever physicians examine a patient presenting with a new mass in the leg, thigh, muscles, and deep tissue of the body, particularly if the patient has a previous history of cancer, metastatic cancers in the soft tissues should be considered. The most likely cancers to metastasize to soft tissue are cancers of the lung and kidney.

Links:

[1] https://www.cancer.gov/types/soft-tissue-sarcoma

[2] https://www.cancer.org/cancer/rhabdomyosarcoma/about/what-is-rhabdomyosarcoma.html

[3] https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms?expand=D

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.3.1.pdf

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.3.1.csv

[6] https://www.cancer.org/cancer/soft-tissue-sarcoma/about/key-statistics.html

[7] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30737668

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.3.2.pdf

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.3.2.csv

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.6.2.pdf

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.6.2.csv

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a21png

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.2.1.png

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.1.3.pdf

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.1.3.csv

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.7.pdf

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.7.csv

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.1.4.pdf

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.1.4.csv

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a22png

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.2.2.png

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.5.1.pdf

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.5.1.csv

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.8.pdf

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.8.csv

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a23png

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.2.3.png

[28] https://www.cancer.org/cancer/soft-tissue-sarcoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.2.8.pdf

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.2.8.csv

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a24png

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.2.4.png

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.2.6.pdf

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.2.6.csv