[8]

[8]

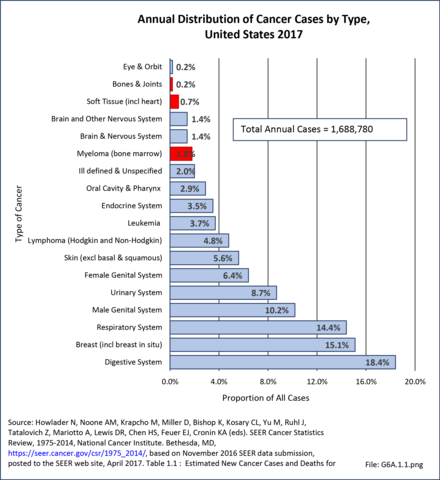

Bone and connective tissue neoplasms, which include bone and joint sarcomas, myelomas, and soft tissue sarcomas, are uncommon when compared with other cancers and with other musculoskeletal conditions, accounting for about 2.4% of annual cancer cases between 2010 and 2014 (approximately 50,000 cases). This share is higher than the 2.2% reported for 2006 to 2010, and the 1.9% for 2002 to 2006. Estimated cases for 2017 were slightly lower, at 46,000 cases, but represented 2.7% of all new cancer cases. The annual average number of new bone and joints cancer cases, excluding myeloma and soft tissue, reported between 2010 and 2014 was 4,126 cases, with an average of 1,440 deaths from bone and joints cancer each year. Estimates for 2017 are 3,260 new cases and 1,550 deaths. Data cited is from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute and is used to illustrate the burden of bone and connective tissue neoplasms. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.0 PDF [1] CSV [2], Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [3] CSV [4]; and Table 6A.A.1.4.1 PDF [5] CSV [6])

The three most common primary cancers of bones and joints are osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma. Together they account for more than 80% of true primary bone and joint cancers. The ages at which these cancers most often occur vary. Osteosarcoma, a malignant bone tissue tumor commonly found near the growing end of the long bones, is the most common, and occurs most frequently in teens and young adults. Ewing sarcoma, a tumor often located in the shaft of long bones and in the pelvic bones, occurs most frequently in children and youth. Chondrosarcoma, a sarcoma of malignant cartilage cells, often occurs as the result of malignant degeneration of pre-existing cartilage cells within bone, including enchondromas (a benign tumor), and is primarily found among middle age and older adults. However, the majority of enchondromas never undergo malignant change; therefore, the routine resection of benign enchondromas is unwarranted. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.1 PDF [9] CSV [10], Table 6A.B.1.2 PDF [11] CSV [12], Table 6A.B.1.3 PDF [13] CSV [14], and Table 6A.B.1.4 PDF [15] CSV [16])

Of the three, chondrosarcoma has the best prognosis, while Ewing sarcoma is generally considered to have the worst prognosis, followed closely by osteosarcoma. However, this perception is largely due to the greater tendency for osteosarcomas to present as high-grade tumors and for chondrosarcomas to present as low-grade tumors. When analyzed by stage, a recent survivorship analysis of a prior cohort of patients in the NCDB PUF database revealed similar survivorship rates for low-grade chondrosarcoma compared to low-grade osteosarcoma, and similar survivorship rates for Ewing sarcoma and high-grade osteosarcoma. By definition, all cases of Ewing sarcoma are high-grade, the most aggressive category of cancer, with full potential to metastasize and bring about death. High-grade chondrosarcoma has a worse prognosis when compared to high grade osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma.1

In the current NCDB analysis, only 4% of osteosarcomas are of Grade 1, the lowest grade, whereas 48% of chondrosarcoma are Grade 1. Therefore, chondrosarcomas have a higher proportion of low-grade cases than the other two bone and joint cancers, which accounts for its overall higher survival rate and the perception that it is not be as lethal. Conversely, 2% of all chondrosarcomas with histologic grading were reported as Grade 4, whereas 40% of osteosarcomas were reported as being in the most aggressive Grade 4 category. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.8 PDF [19] CSV [20])

A fourth type of cancer is myeloma, a malignant primary tumor of the bone marrow formed from a type of bone marrow cells called plasma cells (the cells that manufacture antibodies). Although not classified as a bones and joint cancer, it typically causes extensive changes or damage to the bone structure itself, causing fractures, pain, and hypercalcemia (a condition in which the calcium level in blood is above normal, which can weaken bones, create kidney stones, and interfere with how the heart and brain work). Because of the associated bone destruction, myeloma is generally included in analysis of bone cancers. Myeloma usually involves multiple bones simultaneously. The isolated single-bone version of myeloma is called plasmacytoma, but virtually all cases of isolated plasmacytoma evolve into full-fledged multiple myeloma within 5 to 10 years after diagnosis of the plasmacytoma. Like leukemia and lymphoma, myeloma is more properly considered a primary cancer of the hematopoietic bone marrow (stem cells that give rise to other blood cells.). However, leukemia and lymphomas generally are not considered primary bone cancers, presumably because of the lower likelihood of structural bone destruction and associated complications. NonHodgkin's lymphomas, however, as well as myelomas, warrant some consideration in a report on the burden of musculoskeletal diseases due to the frequency of bone destruction and pathological fractures requiring operative intervention.

The reader is referred to the data tables 6A.B.1.1 thru 6A.B.1.9 for a more robust appreciation of these tumors. These tables show the latest NCDB demographic and survivorship analyses of bone and joint cancers, providing additional understanding of the demographics, age distribution, anatomic distribution, nature, treatment and prognosis of these sarcomas and their treatments and results.

Adamantinoma: A rare bone cancer, making up less than 1% of all bone cancers. It almost always occurs in the bones of the lower leg and involves both epithelial and osteofibrous tissue. It generally has a favorable prognosis.

Angiosarcoma: A cancer that forms from cells that are in the lining of blood vessels and lymph vessels. It often affects the skin and may appear as a bruise-like lesion that grows over time. The disease most commonly occurs in the skin, breast, liver, spleen, and deep tissue. It typically has an aggressive course and a poor prognosis.

Chondroblastoma – malignant: Chondroblastoma is a rare, usually benign, tumor of cartilaginous origin. It typically arises in the epiphysis of a long bone. Malignant chondroblastomas, which may occur many years after the original lesion, are extremely rare. Our analysis of the NCDB database reveals a usually good prognosis, with 95% survivorship at 5 years. Establishing the diagnosis in such rare and unusual cases is challenging at best. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.1 PDF CSV)

Chondrosarcoma: A bone cancer that develops from cartilage cells. Cartilage is the specialized, gristly connective tissue that is on the ends of bones with articulating joints that cushion the bone ends and allow motion over its smooth lubricated surfaces. Primitive cartilage is present in adults and the tissue from which most bones develop. Chondrosarcoma develops primarily in the pelvis, scapulae, chest bones, long bones, and spine.

Chordoma: A rare type of slow growing cancerous tumor that can occur anywhere along the spine, from the base of the skull to the tailbone. It derives from the notochord, an embryonic tissue generally considered to be the precursor to intervertebral disc tissue.

Ewing sarcoma: A cancerous tumor that grows in the bones or in the tissue around bones (soft tissue)—often the legs, pelvis, ribs, arms, or spine. Ewing sarcoma can spread to the lungs, bones, and bone marrow.

Fibrosarcoma: A malignant tumor consisting of fibroblasts (connective tissue cells that produce the collagen found in scar tissue) that may occur as a mass in the soft tissues or may be found in bone.

Giant cell tumor of bone - malignant: A relatively uncommon tumor of bone characterized by the presence of multinucleated giant cells (osteoclast-like cells). Malignancy in giant-cell tumor is uncommon and occurs in about 2% of all cases. However, if malignant degeneration does occur, it is likely to metastasize to the lungs. It often arises in sites of previously treated benign giant cell tumors that were treated with radiation therapy.

Hemangioendothelioma: A rare type of vascular tumor that affects the epithelial cells which line the inside of blood vessels. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma tumors most commonly affect the soft tissues, liver, lungs, and bones.

Leiomyosarcoma: A type of soft tissue sarcoma that develops in muscle, fat, blood vessels, or any of the other tissues that support, surround, and protect the organs of the body. Leiomyosarcoma is one of the more common types of soft tissue sarcoma to develop in adults.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: Most often more recently classified as pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) also can be listed as plasmosphic sarcoma not otherwise specified (PS-NOS). It also was often formerly known as a type of fibrosarcoma. It is historically considered the most common type of soft tissue sarcoma. It has an aggressive biological behavior and a poor prognosis, and primarily affects the extremities.

Neoplasm - malignant: The term "malignant neoplasm" means that a tumor is cancerous. When diagnosed it may mean further testing is needed to identify the specific type of cancer or sarcoma.

Osteosarcoma: The most common type of cancer that starts in the bones. The cancer cells in these tumors look like early forms of bone cells that normally help make new bone tissue, but the bone tissue in an osteosarcoma is not as strong as that of normal bones. Therefore, affected bones are subject to pathologic fracture (fractures caused by bone weakened due to underlying disease). Without proper treatment, osteosarcome is fatal.

Primitive peripheral neuroectodermal tumor: Primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) are a group of highly malignant tumors composed of small round cells of neuroectodermal origin that affect soft tissue and bone. PNETs exhibit great diversity in their clinical manifestations and pathologic similarities with other small round cell tumors. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors (pPNETs) are tumors derived from tissues outside the central and autonomic nervous system.

Sarcoma (NOS): A usually aggressive malignant mesenchymal cell tumor most commonly arising from muscle, fat, fibrous tissue, bone, cartilage, and/or blood vessels that is not otherwise specified (NOS).

SEER estimates an average of 3,260 people were newly diagnosed with cancer of the bones and joints, excluding myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemias, in 2017. During the same year, an estimated 1,550 people died from cancer of the bone and joints. The number of new cases of bone and joint cancers was estimated to be 1.0 per 100,000 people per year during the years 2012-2016.1 However, death rates from bone and joint cancers have declined slightly (0.2% per year) since 1982-2016, following a 9.9% decline from 1975-1982.2 Approximately 40% of bone cancers are diagnosed at a localized stage, for which the 5-year relative survival is 85%.3 The overall 5-year relative survival rate in the 2004-2015 NCDB Database set for Bone and Joint cancers was 65% but is higher for all combined chondrosarcomas (74%) than all combined osteosarcomas (60%). (Reference Table 6A.A.1.0 PDF [1] CSV [2] and Table 6A.A.1.5.1 PDF [23] CSV [24]. See Table 6A.B.1.1 PDF [9] CSV [10] and Table 6A.B.1.2 PDF [11] CSV [12] for the NCDB database data regarding the two- and five-year survivorship of all bone and joint sarcomas.)

Myeloma occurs up to ten times more frequently than bone and joint cancers and is not defined as a rare cancer as the incidence is just over the 6/100,000 rare cancer definition. In 2019, myeloma was estimated to be diagnosed in 32,110 persons per year, an incidence rate of 6.9 per 100,000 persons per year. An estimated 12,960 persons will die of myeloma in 20194, with a death rate of 3.3 per 100,000 persons. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.2.1 PDF [27] CSV [28] and Table 6A.A.1.2.2 PDF [29] CSV [30])

Most bone cancers and soft tissue sarcomas are found more frequently in males than females and more frequently among whites than those of any other race, although there are exceptions or outliers to these generalizations for certain subtypes of bone and soft tissue tumors. However, reported rates have varied slightly for both genders and by race for the past decade. The average annual incidence of bone and joint cancers between 2012 and 2016 was 1 in 100,000, a slightly higher rate than reported in the first decade of the 21st century. The rate among white males was 1.2 in 100,000, while, among white females it was 0.9 in 100,000. The lowest reported rate, 0.6/100,000 was found for females of the Asian or Pacific Islander race. The incidence of cancer of the bones and joints in the United States is comparable to several site-specific oral cancers (i.e., lip, salivary gland, floor of the mouth), cancers of the bile duct, cancers of the eye, and Kaposi's sarcoma, which affects the skin and mucous membranes and is often associated with immunodeficient individuals with AIDS. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.1.1 PDF [35] CSV [36] and Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [3] CSV [4])

As with bone and joint cancers, males have a higher incidence of myeloma than do females, with an average of 8.1 cases in 100,000 white males to 4.9 cases in 100,000 white females for the years 2012-2016. Blacks have a much higher incidence rate of myeloma than whites, with 16.3 cases in 100,000 black males to 11.9 cases in 100,000 black females for the years 2012-2016 while American Indians/Alaska Natives and Asian/pacific islanders have lower incidence rates. The incidence of myeloma in the United States is comparable to the incidence of esophageal, liver, cervical, ovarian, brain, and lymphocytic leukemia cancers. Death rates reflect incidence. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.2.1 PDF [27] CSV [28] and Table 6A.A.1.2.2 PDF [29] CSV [30])

The gender make-up of bone and joint cancers from the most recent NCDB (2004-2015) cohort also shows a male predominance for most of the bone and joint cancers and cancer subtypes, with parosteal osteosarcoma showing the major break from this generalization with 34% male and 66% female patients with this cancer. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.6 PDF [41] CSV [42] and Table 6A.B.1.7 PDF [43] CSV [44])

The median age for cancers of the bones and joints has risen slightly, to age 43 years, in recent years. However, it remains the leading cause of cancer in young persons under the age of 20 years. More than one in four (26%) diagnoses of bone and joints cancer is in children and youth under the age of 20 years, with 42% of cases diagnosed in persons younger than 35 years. Death from bone and joints cancer also affects children and youth at a high rate, with 12% of deaths occurring in those under 20 years of age and one fourth (27%) in those younger than 35 years. Males are typically diagnosed with bone cancers, and die from bone cancer, at an age several years younger than females. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [3] CSV [4]; Table 6A.A.1.4.1 PDF [5] CSV [6]; Table 6A.A.1.7 PDF [45] CSV [46]; and Table 6A.A.1.8 PDF [47] CSV [48]).

Younger patients have a higher likelihood of surviving bone cancers. For example, the 5-year survivorship for classic osteosarcoma is 67% in 10 to 20-year-old patients, compared to 34% in patients in their 60s, 19% for patients in their 70s, and only 7% in patients in their 80s and older. Similar declining survivorship is noted with increasing age for Ewing Sarcoma and chondrosarcoma (unpublished NCDB current data analysis).

Myeloma, on the other hand, is primarily a cancer found among elderly persons, with a median age of 69 at the time of diagnosis and 75 at time of death from myeloma. Sixty-two percent (62%) of new myeloma cases are diagnosed in persons age 65 years and older, with more than three in four (78%) of deaths due to myeloma occurring in those 65 and older. Again, males are typically diagnosed with myeloma at ages a few years younger than females. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [3] CSV [4]; Table 6A.A.1.4.1 PDF [5] CSV [6]; Table 6A.A.1.7 PDF [45] CSV [46]; and Table 6A.A.1.8 PDF [47] CSV [48])

The incidence of bone and joints cancers is higher among non-Hispanic whites than found in other race/ethnicity groups, while myeloma is higher in non-Hispanic blacks. Death rates follow the same race/ethnic lines. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.1.1 PDF [35] CSV [36]; Table 6A.A.1.1.2 PDF [51] CSV [52]; Table 6A.A.1.2.1 PDF [27] CSV [28]; and Table 6A.A.1.2.2 PDF [29] CSV [30])

Causes of health disparities are complex and can include interrelated social, economic, cultural, environmental, and health system factors, and may arise, at least in part, from inequities in work, wealth, education, housing, and overall standard of living, as well as social barriers to high-quality cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment services.1

Annual population-based mortality rates due to cancers of bones and joints are low, averaging four deaths per one million people since the early 1990s.1 While the mortality rate from bone and joint cancer dropped by approximately 50% from that of the late 1970s, no significant improvement in this rate has been observed over the past 20 years.2 Males have a higher mortality rate than females for all race/ethnic groups. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.1.2 PDF [51] CSV [52])

Because bone and joint cancers affect younger populations more than other types of cancers, the median age at death, 61 years of age, is younger than any other type of cancer. There is a higher death rate in older individuals, but a higher incidence rate in younger individuals. At 0.1% risk, bone and joints cancer also has one of lowest life-time risks. This compares to 12% risk for breast and prostate cancer, the two highest risk cancers. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.5.1 PDF [23] CSV [24] and Table 6A.A.1.6.1 PDF [53] CSV [54]; and Table 6A.A.1.6.2 PDF [55] CSV [56])

The overall 5-year survival rate in 2009-2015 for bone and joint cancers was 66.2%, placing it roughly in the middle of all cancers for 5-year survival and comparable to several more common cancers such as rectal, cervical, and soft tissue cancers.3 This is a survival rate increase of 27% since 1975, when the 5-year survival rate was 52%. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.5.2 PDF [57] CSV [58])

By extrapolation from median age at diagnosis and median age at death, one could estimate a median survival rate. However, this extrapolated survival time is misleading and inaccurate as younger patients, who typically are healthier and can tolerate more aggressive treatments, have improved survival compared to older individuals, who cannot tolerate such aggressive treatments and have poorer survival, greatly affecting this derived or extrapolated estimate of survivorship.

The overall 5-year survival rate for the primary types of bone and joint cancers varies by type and subtype of cancer, how it responds to treatment, and the degree to which the cancer has spread. Osteosarcoma diagnosed and treated before it has spread has a reported general survival rate between 60% and 80%; if it has already spread at the time of diagnosis, the 5-year survival rate is reported to be between 15% and 30%.4

If Ewing sarcoma is found before it metastasizes, the 5-year survival rate for children and youth is about 70%, with a survival rate of 78% reported for children under age 5, dropping to around 60% survival for adolescents age 15 to 19. However, if already metastasized when found, the 5-year survival rate drops to 15% to 30%.5

The annual population-based mortality rate of myeloma has been an average of 33 persons per one million population between 2001 and 2016. The mortality rate from myeloma has remained relatively constant since the mid-1970s. The 5-year survival rate for myeloma, 50%, is one of the lowest for all cancers; however, due to being primarily a cancer of older persons, this age-relatedness may, in part, reflect survival regardless of the presence or absence of myeloma. The median calculated rate of survival after diagnosis of myeloma is only 6 years. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.2.2 PDF [29] CSV [30] and Table 6A.A.1.5.1 PDF [23] CSV [24])

Within the NCDB, no change in the overall survival rates for patients diagnosed and treated in the years 1985 to 1988 compared to patients between 1994 and 1998 was found. There have been no substantial changes in therapies utilized for osteosarcoma since 1998, and the overall 1998-2010 NCDB data reveals no significant improvement, with an approximate 50% 5-year overall survival. However, the survival rate varies greatly with the histologic subtype of sarcoma. For instance, the 5-year relative survival rate is 56% for classic high-grade osteosarcoma, 89% for parosteal osteosarcoma, and 37% for osteosarcoma associated with Paget's disease of the bone. The most recent NCDB database investigation the three primary authors have performed, which covered patients diagnosed between 2004-2015, inclusive, is summarized in the data tables attached to this chapter. These data provide the analysis of the numbers of cases reported during these years, along with the Kaplan-Meier survivorship of the major diagnostic groupings, as well as of the subgroups and age-based for the various primary bone and joint tumors reported and treated 2004-2015. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.1 PDF [9] CSV [10]; Table 6A.B.1.2 PDF [11] CSV [12]; Table 6A.B.1.3 PDF [13] CSV [14]; and Table 6A.B.1.4 PDF [15] CSV [16])

The above and all other reported survivorships in this chapter were generated using SAS/STAT software, Version14.2 for Windows 3. Copyright 2002-2012, SAS Institute Inc. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA. As stated previously, the NCDB is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The data used in this study and this report are derived from a de-identified NCDB file comprising more than 1,500 Commission-accredited cancer programs. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology employed or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigator and authors of this chapter.

The economic burden of bone cancers can be great. The more advanced the disease, the worse the prognosis and, accordingly, the more expensive the treatments. It is likely that early detection, and, certainly, prevention if possible, could drastically reduce costs. Several expensive treatments are required to address these tumors. In the 2007 report by Damron, Ward, and Stewart,1 it was noted that the most frequent initial treatments varied widely based on the type of sarcoma and, although not reported, also on the stage of the disease as well.

Collectively, they reported surgery alone was the most common initial treatment for chondrosarcomas (69%), whereas Ewing sarcoma treatments were divided between surgery and chemotherapy (24% of cases), radiation and chemotherapy (23%), and chemotherapy alone (18%). With osteosarcoma, when initial treatment was known, the largest group received surgery and chemotherapy (46%). Surgery was reported as part of the initial treatment in 71% of osteosarcoma patients, 83% of chondrosarcoma patients, and 47% of Ewing sarcoma patients. The most frequent operations performed were limb-sparing radical resections and excisions. When the type of surgery was defined and known, limb-preservation surgery was performed in 69% of osteosarcomas, 79% of chondrosarcomas, and 81% of Ewing sarcomas.1

The frequencies of the various treatment modalities employed in the latest reported (2004-2015) NCDB cohort are shown in the data tables attached to this section for bone and joint cancers and soft tissue cancers. As shown in the table, for Osteosarcoma NOS 76% had surgery, 74% had chemotherapy, and only 8% had radiation. For Ewing Sarcoma, the numbers were 51%, 85%, and 45%, respectively. For Chondrosarcoma NOS, the numbers were 85%, 3%, and 10%. These distributions reflect the widely different treatments of these three major categories of bone and joint cancers. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.9 PDF [67] CSV [68] and Table 6A.B.2.6 PDF [69] CSV [70])

In Dr. Ward's personal series of more than 100 osteosarcomas, amputation has been required in only 17% of patients, but almost all remaining patients have had surgical resection, limb reconstruction, and chemotherapy.1 The authors believe Dr Ward’s series is a reasonable approximation of treatments employed by most orthopedic oncologists in the US today.

Multiple therapies may be needed throughout the course of the patient's disease, especially in more advanced cases. In later stages of the disease for those not cured with surgery alone, significant costs will accumulate as patients develop pulmonary disease and ultimately die. Hormone therapy, immunotherapy, bone marrow transplant, and endocrine treatments each accounted for 1% or less of initial treatments. However, in severely affected individuals in whom standard treatments fail, these alternative treatments may be tried more frequently. Currently, the authors are not aware of any data source that reports the rate of utilization of such late treatments.

All these treatments are costly to administer. Per-patient cost will vary widely depending on the treatments utilized, and the number and intensity of treatments. Overall, treatment for bone and joint cancers can easily exceed $100,000 for a single patient. This is particularly true if a patient receives surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. If one includes bone-replacing endoprostheses or artificial limbs used in cases requiring amputation, the cost will be much higher. In addition to the direct medical cost, there are extensive indirect and social costs from lost work time and disability. For some patients, healthcare costs associated with their bone and joint cancers will be ongoing.

Analysis of the most recent NCDB insurance data, which covers all ages and covers the years 2004-2015 inclusive, available for 18,881 reported bone and joint cancer cases show Medicare and Medicaid covering 16.76% and 14.71%, respectively, with private insurance covering 57.33%, other government payors covering 1.9% with 5.05% uninsured and 4.24% with unknown insurance status. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.11 PDF [73] CSV [74])

Almost all cancers have preferential sites to which they spread or metastasize, resulting in secondary cancers. Secondary bone cancer is much more common than primary bone cancer and results in great morbidity and pain. The three most common sites to which cancers metastasize are lung, liver, and bone. The skeleton is the most common organ affected by metastatic cancer, and the site of disease that produces the greatest morbidity. The most commonly encountered cancers that readily and frequently spread to bone are cancers of the breast, lung, kidney, prostate, gastrointestinal tract, and thyroid gland. The incidence of bone metastases in lung cancer patients is approximately 30% to 40%, with the median survival time (MST) of patients with such metastases 6 to 7 months.1 At postmortem examination, 70% of patients dying of breast and prostate cancer have evidence of metastatic bone disease. Cancers of the thyroid, kidney, and bronchus also commonly give rise to bone metastases, with an incidence at postmortem examination of 30% to 40%.2 Brain and ovarian cancers rarely spread to bone. Many other cancers have intermediate rates of spread to bones.

A tumor formed by metastatic cancer cells is called a metastatic tumor or a metastasis. The cancer cells in their new metastatic site closely resemble the original or primary cancer from which the cancer initially arose. For example, breast cancer that spreads to the bone and forms a metastatic tumor is still considered metastatic breast cancer, not true bone cancer. The cancerous tissues in the bone will still exhibit the microscopic appearance of breast tissue and breast cancer when it is inspected or viewed under a microscope. Many lay people will now refer to it as bone cancer, but to the physician, bone cancer implies a cancer that started or originated in the bone, such as osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, or myeloma, as discussed previously.

Metastatic bone disease complications are termed skeletal related events (SREs). SREs include pain, pathologic fracture, vertebral deformity and collapse, spinal cord compression, and hypercalcemia (overabundance of calcium in the blood) of malignancy. These complications result in impaired mobility and reduced quality of life (QOL) and have a significant negative impact on survival.2 In addition, metastatic disease may remain confined to the skeleton, with the decline in quality of life and eventual death almost entirely due to skeletal complications and their treatment.

The prognosis of metastatic bone disease is dependent on the primary site, with breast and prostate cancers associated with a survival measured in years compared with lung cancer, where the average survival is only a matter of months. Survival rates for secondary bone cancer depend on patient factors such as age, overall health, treatment, and response to treatment. However, due to the advanced stage of cancer that has spread to the bone, survival rates are much lower than for primary cancer without such spread.

The fundamental treatment for disease control for bone metastasis from advanced cancer is systemic chemotherapy and radiation of the bone lesions. Prevention and treatment of bone metastases is highly dependent on an effective treatment being employed against the primary cancer. As a direct treatment for bone metastases themselves, radiation therapy, surgery, and bisphosphonates are the mainstays of treatment. Intravenous bisphosphonate, such as zoledronic acid, have been shown to prevent or reduce pathologic fractures and may reduce these costs.3 With the 1995 FDA approval of the use of bisphosphonate medications to prevent such fractures, the incidence of fractures in treated patients with bone metastasis has significantly decreased. Fracture rates reported in cases of metastatic disease and myeloma have been demonstrated in multiple studies to be diminished by roughly 50%. The bisphosphonate medications work by interrupting a biochemical pathway required for bone breakdown by osteoclasts, the cells that normally remove bone in the process of bone remodeling. This bone breakdown step is overactivated in the presence of bony metastases, causing bone loss, bone destruction, and ultimately fractures from the weakening of the bone. Thus, the introduction of bisphosphonate medication has been a major advance during the past 20 years, with significant impact on the health of those with myeloma and metastatic cancer to the bone. Most pathologic fractures encountered currently are in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic cancer who have not received prophylactic treatments because the cancer had not been diagnosed.

Dr. Ward has had several anecdotal cases in the last year (2018-2019) with metastatic lung and other cancers that have metastasized to bone in whom the cancer elsewhere in the body is responding favorably to newer targeted chemotherapy and immunotherapy regimens, but the bone metastasis for some reason is not responding favorably, requiring more extensive surgical treatment of the unresponsive bone metastatic lesion. Whether or not this will become a more common challenge in the future is anyone’s guess, but with several cases seen by one physician in a short time, it raises the possibility that more extensive bone resection treatments may become more necessary for metastatic bone lesions as these individualized systemic targeted treatments are employed in greater numbers and are capable of controlling the disease in the rest of the body.

The economic burden of SREs in patients with bone metastases is substantial. Several recent studies show that the estimated lifetime SRE-related cost per patient suffering from bone metastatic disease (BMD) resulted in medical costs more than twice the treatment cost for cancer in patients without BMD.1,2 Finding cures and effective treatments for all types of cancer can help reduce the prevalence and costs associated with bone and joint cancer.

Overall, cancers metastatic to bone cause significant pain and morbidity. Approximately 50% of patients with metastatic cancer of lung, breast, prostate, and kidney develop bony metastases prior to death. Untreated, these metastases can lead to pathological fractures and cause great pain and disability. Thus, the elucidation of the biochemical steps involved in bone destruction and the development of drugs to combat such steps, have been an example of tremendous scientific advancement and achievement in the field of cancer research and treatment.

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.0.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.0.csv

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.3.1.pdf

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.3.1.csv

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.4.1.pdf

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.4.1.csv

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a11png

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.1.1.png

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.1.pdf

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.1.csv

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.2.pdf

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.2.csv

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.3.pdf

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.3.csv

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.4.pdf

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.4.csv

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a12png

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.1.2.png

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.8.pdf

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.8.csv

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a13png

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.1.3.png

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.5.1.pdf

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.5.1.csv

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a14png

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.1.4.png

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.2.1.pdf

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.2.1.csv

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.2.2.pdf

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.2.2.csv

[31] https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer

[32] https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer

[33] https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf

[34] https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.1.1.pdf

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.1.1.csv

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a15png

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.1.5.png

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a16png

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.1.6.png

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.6.pdf

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.6.csv

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.7.pdf

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.7.csv

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.7.pdf

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.7.csv

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.8.pdf

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.8.csv

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a17png

[50] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.1.7.png

[51] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.1.2.pdf

[52] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.1.2.csv

[53] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.6.1.pdf

[54] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.6.1.csv

[55] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.6.2.pdf

[56] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.6.2.csv

[57] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.5.2.pdf

[58] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.A.1.5.2.csv

[59] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a18png

[60] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.1.8.png

[61] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a19png

[62] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.1.9.png

[63] https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/bones.html

[64] https://surveillance.cancer.gov/statistics/types/survival.html

[65] https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/osteosarcoma-childhood/statistics

[66] https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/ewing-sarcoma-childhood-and-adolescence/statistics

[67] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.9.pdf

[68] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.9.csv

[69] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.2.6.pdf

[70] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.2.6.csv

[71] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a110png

[72] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.1.10.png

[73] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.11.pdf

[74] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_T6A.B.1.11.csv

[75] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg6a111png

[76] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g6a.1.11.png

[77] https://www.mdedge.com/hematology-oncology/article/47005/genitourinary-cancer/impact-bone-metastases-and-skeletal-related