[4]

[4]

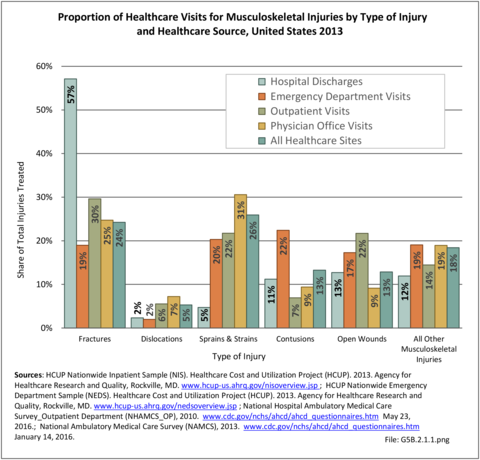

Healthcare visits for treatment of musculoskeletal injuries include hospital discharges, emergency department visits, outpatient clinic visits, and physician’s office visits. Overall, 1 out of every 15 healthcare visits (6.8%) is for treatment of a musculoskeletal injury. In 2013, sprains and strains and fractures were the most frequently treated type of musculoskeletal injury. (Reference Table 5B.2.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

Female injured are slightly more likely to be treated in a hospital than male (55% vs 51% of the population). Persons age 65 and over are far more likely to be treated for a musculoskeletal injury in the hospital, while those aged 45 to 64 are more likely to visit a physician’s office. Non-Hispanic whites are treated for musculoskeletal injuries in all healthcare settings more than other racial/ethnic groups. Residents of the Midwest region visit outpatient clinics for injury treatment more than residents of other regions, while those living in the West are most likely to visit a physician’s office for injury healthcare. (Reference Table 5B.2.1 PDF [1] CSV [2]; Table 5B.2.2 PDF [5] CSV [6]; Table 5B.2.3 PDF [7] CSV [8]; Table 5B.2.4 PDF [9] CSV [10])

Nearly 6 in 10 ( 58%) of musculoskeletal injuries for which healthcare treatment was sought were treated in a physician’s office. An additional 3 in 10 were treated in an emergency department and another 1 in an outpatient clinic. Less than 3% were severe enough to require hospitalization. (Reference Table 5B.2.5 PDF [11] CSV [12])

Three out of four (74%) fracture injuries admitted to the hospital are the admitting (first) diagnosis, while one in five other injuries are diagnosed as the admitting diagnoses. The ratio is much higher as the first diagnosis when treated in the emergency department. (Reference Table 5B.3 PDF [15] CSV [16])

Fractures are one of the most common musculoskeletal injuries, and can have long-term impact, particularly among the elderly. In 2013, one in five (24%) musculoskeletal injuries treated in a healthcare facility was for a fracture, with 1 in 20 persons in the population receiving care for a fracture. Data are based on visits in multiple settings and do not represent unique cases. (Reference Table 5B.2.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

Trends in the number of fractures treated between 1998 and 2013 show relatively stable numbers. Around 3 million fractures of the upper and lower limbs are treated in emergency rooms each year, another 9 million in physician’s offices, with about 900,000 upper and lower limb fracture patients hospitalized each year. (Reference Table 5B.5.1 PDF [19] CSV [20])

Fractures of the radius and ulna (lower arm) are the most frequently treated fracture, with 2.7 million treated in 2013. These fractures are usually treated in the emergency department (ED) or a physician’s office, with a third (33%) occurring in the under 18 years of age population. Fractures of the ankle, humerus (upper arm), hand, and foot each account for 1.2 million to 1.6 million of fractures treated. These fractures occur at all ages, but more often in the middle ages of 18 to 64 years. Fracture of the neck of the femur, a serious injury with 77% occurring to persons over age 65 and more often among women, accounting for 68% of first line visits in the hospital or emergency department. Nearly 1.2 million neck of femur fractures visits were treated in 2013, with more than one-half (56%) seen initially in the ED or the hospital. (Reference Table 5B.5.2 PDF [23] CSV [24])

In 2013, fractures of the lower limb first treated in the ED had a higher rate of transfer to the hospital (35%) than did upper limb fractures (10%). This is likely due to neck of femur fractures in the older population, as 66% of lower limb fractures for persons age 65 and older treated in the ED were transferred to the hospital. However, fractures to the trunk were the most serious, and 42% treated in the ED were transferred to the hospital. When hospitalized fracture patients were discharged, more than 1 in 2 (58%) with a lower limb fracture were discharged to skilled nursing, intermediate care, or another facility, while another 11% had home healthcare. Among discharged patients age 65 and over, 80% with a lower limb fracture went to additional care while 8% had home healthcare. (Reference Table 5B.5.3 PDF [27] CSV [28]; Table 5B.5.4 PDF [29] CSV [30])

Sprains and strains are the most common musculoskeletal injuries treated in any healthcare facility. In 2013, one in five (26%) musculoskeletal injuries treated in a healthcare facility was for a sprain or strain, with 1 in 18 persons in the population receiving care for a sprain or strain. (Reference Table 5B.2.1 PDF [1] CSV [2]) Sprains and strains occur on a wide continuum of severity, and while mild sprains can be successfully treated at home, severe sprains sometimes require surgery to repair torn ligaments.

In 2013, sprains and strains of the back and sacroiliac joint comprised nearly one-third (30%, 7.1 million treatment episodes) of all sprains and strains for which healthcare treatment was given. Most were seen in a physician’s office (71%), with nearly all the remaining persons seen in an emergency department. Approximately 11,000 sprains and strains of the back and sacroiliac joint required hospitalization. Slightly more than 5 million sprains and strains of the shoulder and upper arm were seen by healthcare providers, as were 4.2 million sprains and strains of the ankle and foot. All totaled, more than 24 million persons with sprains and strains received medical care for these injuries in 2013. (Reference Table 5B.6.1 PDF [33] CSV [34])

When evaluated by age, in 2013 more sprains and strains were treated in persons aged 18 to 44 years than other age groups, followed by the 45 to 64 years of age group. Although there is some difference by sex, overall sprain and strain injury treatments reflect the distribution of male and female individuals in the population. The one exception is the 58% of hospital treatment for sprains and strains of the knee and leg which affect more male individuals. (Reference Table 5B.6.2 PDF [37] CSV [38])

Penetrating trauma is an injury caused by a foreign object piercing the skin, which damages the underlying tissues and results in an open wound. The most common causes of such trauma are gunshots, explosive devices, and stab wounds. Depending on the severity, it can be a puncture wound (sharp object pierces the skin and creates a small hole without entering a body cavity, such as a bite), a penetrating wound (a sharp object pierces the skin, creating a single open wound, AND enters a tissue or body cavity, such as a knife stab), or a perforating wound (object passes completely through the body, having both an entry and exit wound, such as a gunshot wound).

The most common causes of penetrating trauma in the US are gunshots and stabbings. One recent study found approximately 40% of homicides and 16% of suicides by firearm involved injuries to the torso.1 As recently as 2003, the US led in firearms-related deaths in all economically developed countries.2

A 2010 study of 157,045 trauma patients treated at 125 US trauma centers found the incidence of penetrating trauma to be significantly less than blunt trauma. Only 6.4% of all injuries were gunshots, while 1.5% were stab wounds.3 Yet, significant geographic variations and racial differences in the incidence of penetrating trauma exist. In a Los Angeles study of 12,254 trauma patients, 24% of patients treated had sustained penetrating trauma. In a similar Los Angeles study, penetrating trauma accounted for 20.4% of trauma cases, yet resulted in 50% of overall trauma deaths—most of which were due to gunshot wounds.4 Hence, the precise incidence of penetrating chest injury varies depending on the urban environment and the nature of the review. Overall, reported findings show penetrating chest injuries account for 1% to 13% of trauma admissions, and acute exploration is required in 5% to 15% of cases; exploration is required in 15% to 30% of patients who are unstable or in whom active hemorrhage is suspected.5

Although hospital and emergency department visits for penetrating injuries are a small proportion of total visits (<1%), in 2013 there were 76,000 hospital discharges and 290,400 emergency department (ED) visits with an external cause of injury defined as assault by firearms, explosives, or cutting/piercing instrument. Cutting/piercing instruments were identified for about two-thirds of the injuries (45,500 hospital discharges and 19,300 ED visits). Most of the remaining cases listed a firearm cause. (Reference Table 5B.7.1 PDF [41] CSV [42])

Males constituted a majority of persons with penetrating injuries, particularly when caused by firearms (88%) and explosives (80-85%). Two-thirds of penetrating injuries (66%-67%) occurred to persons age 18-44, even though this age group represents on 36% of the population. Residents in the South region had slightly higher rates of penetrating injuries than representative of its population. (Reference Table 5B.7.1 PDF [41] CSV [42])

Looking at a five-year trend for penetrating injuries by race shows black, non-Hispanics carry a larger share of firearms injuries than expected for the population share, but only a slightly higher share of injuries caused by explosives or cutting/piercing instruments. (Reference Table 5B.7.3 PDF [47] CSV [48])

Hospital charges to treat injuries from firearms ($102,300) and explosives ($12,600) are much higher, on average, than the cost for all musculoskeletal injuries or all hospital discharges. Average charges for stabbing injuries ($35,400) are lower than for other causes of hospital stay. Overall in 2013, penetrating injuries accounted for $4.8 million in hospital charges. (Reference Table 5B.7.2 PDF [51] CSV [52])

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.1.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.1.csv

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b211png

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.2.1.1.png

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.2.pdf

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.2.csv

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.3.pdf

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.3.csv

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.4.pdf

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.4.csv

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.5.pdf

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.5.csv

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b212png

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.2.1.2.png

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.3.pdf

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.3.csv

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b213png

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.2.1.3.png

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.1.pdf

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.1.csv

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b511png

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.1.1.png

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.2.pdf

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.2.csv

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b512png

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.1.2.png

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.3.pdf

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.3.csv

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.4.pdf

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.4.csv

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b513png

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.1.3.png

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.6.1.pdf

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.6.1.csv

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b521png

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.2.1.png

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.6.2.pdf

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.6.2.csv

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b522png

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.2.2.png

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.1.pdf

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.1.csv

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b531png

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.3.1.png

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b532png

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.3.2.png

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.3.pdf

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.3.csv

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b533png

[50] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.3.3.png

[51] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.2.pdf

[52] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.2.csv

[53] https://www.jems.com/articles/print/volume-37/issue-4/patient-care/penetrating-trauma-wounds-challenge-ems.html