[10]

[10]

Myopathies are a group of primary muscle disorders causing muscle weakness, occasionally stiffness, and rarely muscle pain. They can be classified into inherited or acquired myopathy. Acquired myopathy can be further divided into idiopathic (cause unknown), infectious, metabolic, inflammatory, endocrine, and drug induced based on the etiology. Depending on the involvement, the patient can present with difficulty with mobility, including difficulty with rising from a chair, stair negotiation, or walking, and impaired activities of daily living, such as dressing and personal care due to difficulty raising the arms. Sensation is not primarily affected although the pain is not uncommon.

Inherited Myopathy

Inherited myopathy has a genetic basis and is passed from parent to child. The muscular dystrophies are the most well-known form of inherited myopathy, with progressive weakness and degeneration of the muscles controlling movement. Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the most common form of muscular dystrophy, primarily affecting 1 boy in 3,300, and is caused by absence of dystrophin, a protein in the muscle cell membrane. Other muscular dystrophies include Becker muscular dystrophy, which is less severe than Duchenne MD; fascioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSH, FSHD), in which the muscles of the face, shoulder blades, and upper arms are most affected; and myotonic muscular dystrophy, characterized by progressive muscle wasting and weakness with prolonged muscle contractions (myotonia) and inability to relax certain muscles after use.

Acquired Myopathy

Inflammatory myopathy, the most common acquired myopathy, includes a group of myopathies with chronic muscle inflammation marked by weakness and, occasionally, muscle pain. It is reported to occur in 8.9 in 1,000,000 persons, with prevalence gradually increasing over the time due to improved diagnostic techniques.1 Other forms of acquired myopathy can be secondary to infection, drugs ortoxins, or systemic (typically endocrine) disorders. Polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and inclusion body myositis are the common inflammatory myopathies.

Neuromuscular Junction Disorders

Myathenia gravis is a disorder affecting neuromuscular junctions, the contact points between the muscles and nerves. It presents with fatigue, fluctuating weakness, typically affecting the muscles that control eye and eyelid movement, chewing, and talking, resulting in drooping of the eyelid (ptosis), difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) or speaking (dysarthria).

Patients with myopathy are likely to utilize ambulatory visits, specialist visits, and hospitalization more often than those without myopathy, according to a study of the patients with inflammatory myopathy in a large managed care system.1 Diagnostic tests, including EDx, blood and genetic testing and muscle biopsy, are often utilized to confirm clinical suspicions from history and physical examination, and to delineate the exact type and underlying etiology of myopathy. As cure is limited in most myopathies, treatment focuses on the supportive and symptomatic treatment. In the initial stages and/or milder forms of myopathy, treatment is usually at an outpatient clinic for physical, occupational, and speech therapy, and bracing if needed. In progressive and disabling myopathies, hospitalization is required to manage the secondary problems related to the myopathies such as respiratory failure.

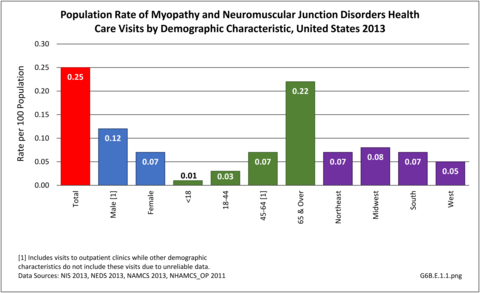

There were 792,700 health care visits made in 2013 with a diagnosis of myopathy or neuromuscular junction disorder. As with some other neuromuscular conditions, the overall number of visits to outpatient clinics and physician’s offices were too small to include in demographic analysis, and affect rates of incidence by demographic characteristics except for males and persons age 44-65 visits to outpatient clinics. Gender and geographic region are not factors, but as with other neuromuscular conditions, the condition increases with age. Racial differences are difficult to determine due to small sample sizes and unreliable data. (Reference Table T6B.1.1 PDF [1] CSV [2]; Table 6B.1.2 PDF [3] CSV [4]; Table 6B.1.3 PDF [5] CSV [6]; and Table 6B.1.4 PDF [7] CSV [8])

More than half (56%) of 792,700 2013 health care visits with a diagnosis of myopathy or neuromuscular junction disorder were to a physician’s office; however, data was not reliable at the level of sub-category conditions. The remainder of visits were spread between hospital discharges (13%), ED visits (13%), and outpatient clinics (18%). Acquired myopathy was the most common diagnosis with a hospital discharge, while neuromuscular junction disorder was most common in the ED.most common in the ED. (Reference Table 6B.1.5 PDF [11] CSV [12])

Some myopathies are more common in the elderly, such as inclusion body myositis and myopathy secondary to cholesterol lowering medication (statin myopathy).

Patients with myopathies survive longer with better care and the increasingly recognized negative impact of aging on physical function and quality of life. In addition to age associated loss of muscle mass and strength (sarcopenia), muscle weakness and fatigue from myopathy can limit independence due to mobility and ADL issues.1

Studies of health care costs and resource utilization in patients with inflammatory myopathy in managed health care revealed annual medical costs were higher among newly diagnosed patients and those with existing inflammatory myopathy compared to unaffected controls.1

The direct annual medical cost of Duchene's muscular dystrophy (MD) ranges from $20,000 to over $50,000 depending on the study methodology. Medical costs include direct cost related to the myopathy and secondary problems including cardiac, respiratory, nutritional and spine complications. Medical costs related to MD and its secondary problems both increase over time.2

Mean hospital charges in 2013 for the diagnosis of myopathy was $81,800 for a mean stay of 8.9 days. This was the longest stay and highest mean charges of all neuromuscular disease categories. (Reference Table 6B.2.1 PDF [15] CSV [16] and Table 6B.2.2 PDF [17] CSV [18])

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.1.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.1.csv

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.2.pdf

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.2.csv

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.3.pdf

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.3.csv

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.4.pdf

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.4.csv

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g6be11png

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G6B.E.1.1_0.png

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.5.pdf

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.5.csv

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g6be12png

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G6B.E.1.2_0.png

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.2.1.pdf

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.2.1.csv

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.2.2.pdf

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.2.2.csv