[10]

[10]

Peripheral neuropathy is a condition that develops from a dysfunction of the nerves that transmit motor or sensory information to and from the brain, spinal cord, and the rest of the body. An estimated 20 million people in the United States have some form of the more than 100 types of peripheral neuropathy.1,2 Peripheral neuropathy can be categorized as hereditary or acquired, with diabetes mellitus the most common cause of acquired peripheral neuropathy.1 Alcohol abuse is also a common cause.

Up to 70% of patients with diabetes eventually develop peripheral neuropathy, with symptoms ranging from subtle or no symptoms to tingling, pain, and profound weakness. Symptoms usually involve the longer nerves, affecting the toes, feet, then gradually progress up the body. Sensory symptoms are more common than motor, and pain occurs in 40-60% of patients with documented neuropathy.3

Guillan-Barre syndrome (GBS) is a peripheral neuropathy in which the body’s immune system attacks part of the peripheral nerve. The syndrome is not uncommon, afflicting approximately one person in 100,000. Usually GBS occurs a few days or weeks after a respiratory or gastrointestinal viral infection. Less commonly it occurs following surgery, or vaccination. There has recently been an increased incidence of GBS due to infection from the Zika virus.

Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) is one of the most common inherited peripheral neuropathies, affecting 1 in 2500 people in the United States. It has several forms affecting different parts of the peripheral nervous system. Despite its inherited fashion, the onset of symptoms varies depending on the type and severity, and it can present anytime from childhood to adulthood. Symptoms may involve the foot, lower leg and hand/finger with numbness, tingling, weakness and muscle wasting. Due to weakness, fatigue and impaired gait, quality of life is significantly impaired.4 Some patients with severe involvement are disabled.5

The diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy is made based on clinical presentation, EDx, blood tests, and occasionally biopsy. Genetic testing is utilized in hereditary conditions, especially for women in their reproductive years, and for affected family members.1

There is no cure for most peripheral neuropathies, and health care resources are typically utilized for symptomatic treatment in outpatient settings, e.g., pain management, rehabilitation (including physical and occupational therapy), and bracing. Patients with diabetic neuropathy utilize greater healthcare resources and have higher costs than patients with diabetes without neuropathy.2

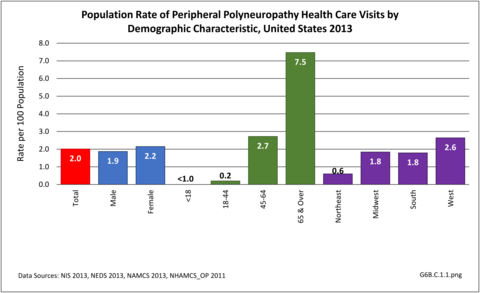

Nearly 6.4 million health care visits in 2013 had a diagnosis of peripheral polyneuropathy, representing 2 in 100 persons in the US. Age is a factor in polyneuropathy, with half (52%) the diagnoses occurring in the 65 and over population. Although males and females had similar rates of diagnosis, females were slightly more likely to have a polyneuropathy diagnosis than males. Because of the small number of diagnoses overall, it is difficult to determine racial/ethnic differences. The western region of the US had a higher share of diagnoses for peripheral polyneuropathy than expected based on population.(Reference Table T6B.1.1 PDF [1] CSV [2]; Table 6B.1.2 PDF [3] CSV [4]; Table 6B.1.3 PDF [5] CSV [6]; and Table 6B.1.4 PDF [7] CSV [8])

Using the definition of hereditary polyneuropathy versus acquired, diagnoses were evenly split between the two types. While visits to a physician’s office represented more than half (58%) of all health care visits with a peripheral polyneuropathy diagnosis in 2013, the share of hospital discharges with this diagnosis was much higher than that of physician office visits (3.0/100 versus 0.4/100). More than one million hospital discharges had a polyneuropathy diagnosis in 2013. (Reference Table 6B.1.5 PDF [11] CSV [12])

The prevalence of peripheral neuropathy increases with age1 and the underlying etiology is diferent among different age groups. In general, manifestations of peripheral neuropathy tend to be severe in the elderly. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy is a significant contributor to falls, fall-related injuries, and overall impaired mobility, compounding the normal decline seen with aging.2 It also impairs activities of daily living and quality of life in the elderly.3

Direct medical costs related to peripheral neuropathy includes costs for diagnostic procedures (EDx, blood, genetic tests, etc), prescription medications (especially for pain medication), rehabilitation costs (physical and occupational therapy and bracing), and costs for complications related to peripheral neuropathy like fractures, non-healing wounds, etc. According to a commercial claims database, there was a 46% increase in the annual cost per patient associated with visits to hospitals, emergency departments, doctors' offices and pharmacy claims after diabetic peripheral neuropathy was diagnosed. The greatest cost increase was associated with hospitalization.1

In 2013, mean hospital charges for discharges associated with peripheral neuropathy were $50,500 for an average stay of 5.8 days. Hospital charges, which totaled $54.4 billion, are not the actual cost due to differences in payment structures, plus the additional cost of professional fees and associated treatments noted above. In addition, nearly half (48%) of hospital discharges were discharged to additional care such as inpatient rehabilitation or skilled nursing facilities. Patients initially seen in an emergency department were, more often than not (61%), admitted to the hospital. (Reference Table 6B.2.1 PDF [15] CSV [16]and Table 6B.2.2 PDF [17] CSV [18])

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.1.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.1.csv

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.2.pdf

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.2.csv

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.3.pdf

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.3.csv

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.4.pdf

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.4.csv

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g6bc11png

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G6B.C.1.1_0.png

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.5.pdf

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.1.5.csv

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g6bc12png

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G6B.C.1.2_0.png

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.2.1.pdf

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.2.1.csv

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.2.2.pdf

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T6B.2.2.csv